Patients with eating disorders commonly exhibit comorbid psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, depression and OCD. The presence of comorbid disorders has been shown to exacerbate the severity and chronicity of the disorder, and unfavourably affect treatment outcome. Moreover, comorbid disorders may necessitate specialized treatment plans that take into account all the co-occuring disorders. Recovery from an eating disorder is hard enough, but when it is complicated by depression and severe anxiety, it can be a lot harder.

Nonetheless, commonly co-occuring psychiatric disorders may also provide researchers and clinicians clues about the etiology of eating disorders, the underlying neuronal processes as well as possible pharmacological interventions.

Researchers have been identifying disorders that commonly co-occur with eating disorders and studying the differences in co-morbidity between disorders. I picked one to write about today, it is a study by Blinder and colleagues that came out in 2007. It is by no means the best, but also not the worst, and of course it has several limitations, which I will mention. But it is a place to start.

This is a retrospective study, meaning that the authors went back through previous medical records, in this case of patients admitted to Remuda Ranch Treatment Center from January 1, 1995 to December 31, 2000. The chief benefit of this approach is the large sample size (2,436 patients in total). The assessments at the treatment center were very thorough and detailed, furthermore a random sample was corroborated independently to ensure diagnostic reliability.

But, there are several downsides from the decision to collect data from Remuda:

- One, it is a faith-based treatment center with “an active religious commitment”, so it biased toward religious patients and families. This of course biases the sample population toward a more ethnically and socio-economically homogeneous group: more than 95% of the sample was white and as much as a third paid out of their own pocket (!!).

- Two, Remuda is a residential treatment center, which in and of itself attracts people that are willing to take the time to go there and do treatment, have the money or health insurance to pay for it, either recognize they are in need of help or are forced by guardians/parents. A treatment-seeking sample (that can afford it). In other words, it likely biases the sample to a much more severe and chronic (less treatment responsive) population (Remuda might not have been the first, second or even third treatment option) than in an outpatient or community population. Given that increased co-morbidity is associated with a protracted outcome, it is no surprise that the frequency of co-morbid disorders reported in this study seem very large.

- No males!

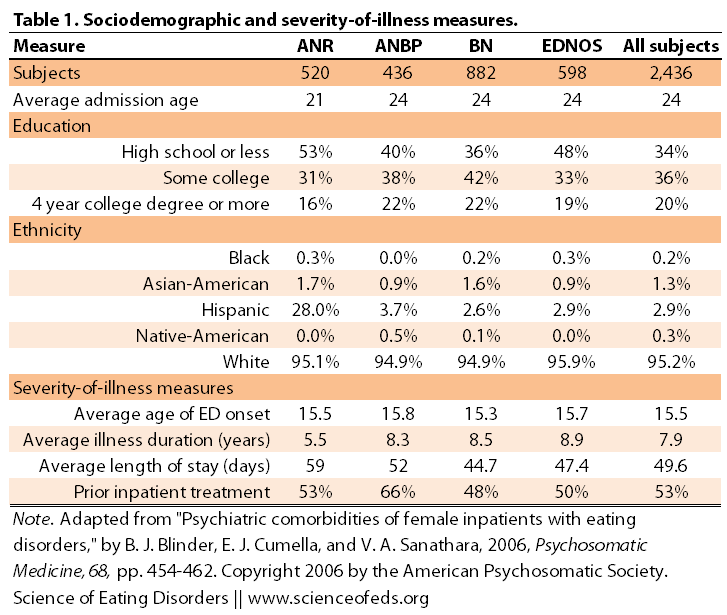

Table 1 summarizes the patient population.

Interestingly, note that patients in the AN-R group are younger and have a shorter duration of the illness compared to the other groups. This is not surprising given the studies on diagnostic crossover and the common fact that restricting, for many, turns to restricting and bingeing/purging (and then, the difference between AN-BP (ANB) and bulimia is just weight).

(The authors controlled for these and other factors in the statistical analyses.)

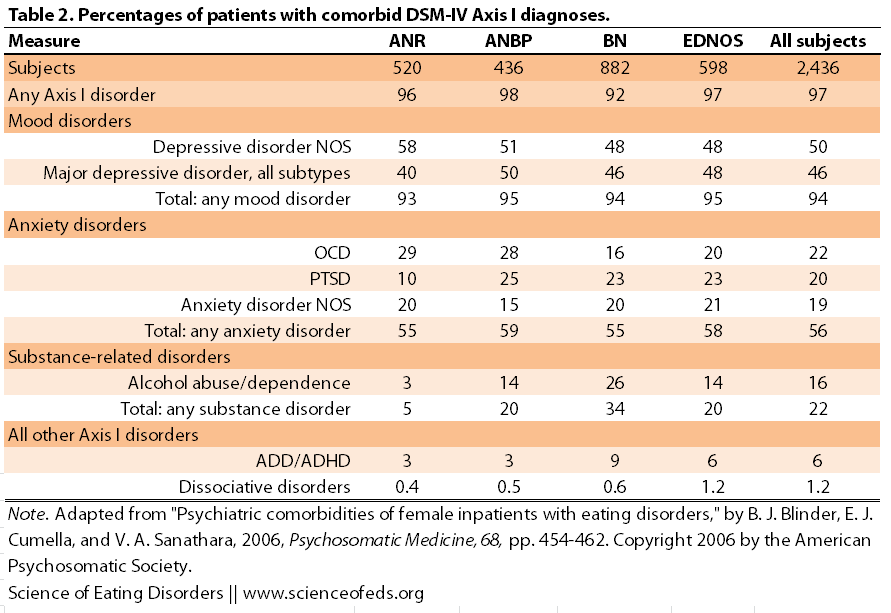

In the end, the analyses included 27 Axis I diagnoses occurring in 10 or more patients. If diagnoses were received by less than 10 people, they were groups together with other disorders, whenever possible. Table 2 summarizes the percentages of patients with Comorbid Axis I diagnoses based on the ED group.

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS:

- all groups had between 96-98% co-occurrence of Axis I disorder

- depressive disorders and major depression co-occur with similar frequency among all groups (40-50%)

- bipolar disorder was the highest in BN and lowest in AN-R (5% vs 2%), but this is not significant.

- total % for any anxiety disorder was similar among all the groups but OCD was most prevalent in AN-R and AN-BP (29 and 28%, respectively) and less common in BN (16%); posttraumatic stress disorder was less common in AN-R (10%) than in the other groups (23-25%)

- alcohol-abuse/dependence was significantly more common in BN than other groups (26% versus 3% in AN-R, and 14% in AN-BP and EDNOS)

- in general, the total for having any substance disorders were: 34% in BN, 20% in AN-BP and EDNOS and 5% in AN-R

- ADD was slightly more common in BN than in other disorders

- schizophrenia was three times more prevalent in AN-R (two times in AN-BP) than in other EDs

- around 0.5% had trichotillomania

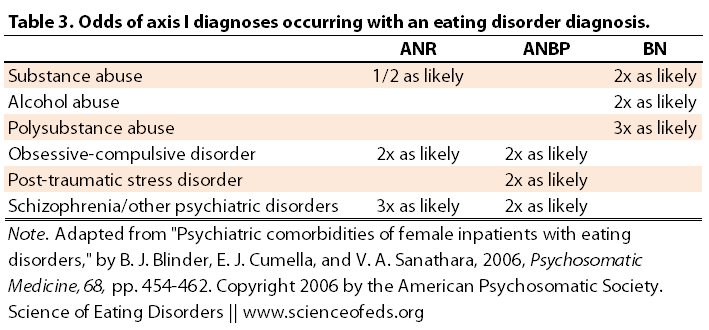

Table 3 summarized the odds of an Axis I diagnoses occurring together with an anorexia, bulimia or ED-NOS. This table sums up the data in Table 2 in a nice way to illustrate the salient findings of the study. EDNOS is a group that contains a mix of subthreshold AN and BN disorders, which likely cancel each other out in terms of the odds.

It is interesting, too, that some co-morbid disorders, like substance-abuse, are more prevalent in binge-eating/purging patients, regardless of AN-BP or BN diagnoses (again, just a difference in weight, really). Whereas others, like OCD for example, was twice as likely anorexia, regardless of the sub-type, than in bulimia.

Besides the aforementioned limitations, it would be nice to compare this data to the non-ED population at large and compare the rates of these disorders not just between different EDs but also between non-ED and ED populations. Even more necessary, I think, would be the comparison between outpatient and community based samples, in addition to just treatment-seeking inpatient groups (albeit that’s likely harder, given the quality of the assessments required for this study.)

In any case, this paper definitely reveals some interesting trends and hopefully other/future studies address some of the limitations in this study, by including a more diverse and heterogeneous population group (ethnic background, socio-economic status, treatment-seeking/non-treatment seeking (how do you study this group in large enough numbers?, males!) and so on.

References

Blinder, B.J., Cumella, E.J., & Sanathara, V.A. (2006). Psychiatric Comorbidities of Female Inpatients With Eating Disorders Psychosomatic Medicine, 68 (3), 454-462 DOI: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221254.77675.f5

“all groups had between 96-98% co-occurrence of Axis I disorders”

That seems CRAZY-high to me, as you noted. Also in regards to the prevalence of OCD in AN vs. BN, I wonder if some significant proportion of the comorbid disorders isn’t in fact a SYMPTOM of the ED rather than a discrete co-occurring disorder? Subpar nutrition and weight and engaging in eating disordered behaviors will result in depression, anxiety and obsessive and/or compulsive cognitions and behavior but I would guess that some of those individuals would have those “comorbid disorders” clear up once weight and nutrition is restored and they stop jacking their brain chemistry via purging etc.

e.g., I don’t have OCD. But when I was sicker in ’07, I sure seemed to: compulsive showering/brushing my teeth/changing my clothes multiple times a day, contamination fears, etc. That largely disappeared with weight and food.

That said, pre-existing comorbid disorders like depression and anxiety probably make individuals more likely to adopt ED behaviors such as a binging, purging, restriction, calorie counting, exercise, et al. as anxiolytic techniques. In my own experience, I was certainly using food pre-ED (and later, restriction/calorie counting) in an attempt to self-medicate my untreated depression.

So how would you account for these in a research study? How would a clinician determine whether or not an individual is exhibiting a true comorbid condition or a symptom of the ED? Also, given that the sample was drawn from a treatment setting where ostensibly, individuals were prevented from engaging in their ED as accustomed, it doesn’t at all surprise me that depression and anxiety rates were high.

Saren, you mean “is in fact a symptom”, not “isn’t in fact a symptom”? Yes, I wonder about that too. I agree completely that malnutrition and starvation increased OCD symptoms and anxiety (predominantly food/weight-related), which often clear-up after weight restoration. The thing is, with OCD, the criteria excludes ED-related OCD behaviors: “E. The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication) or a general medical condition.” BUT, was that followed by the clinicians? I’m not sure. I do suspect that’s part of the reason for the insanely high co-morbidity (however, if you look at the next post, co-morbid disorders are pretty high in male veterans with ED’s, too).

So, they were evaluated at admission and during discharge, and the authors in the study looked at both of those. I wonder how that might have changed the data.

I think it is hard, and I think it has to be done, as much as possible, by assessing the individual’s history prior to the onset of the ED, or assessing those symptoms during the course of the ED and seeing how they vary with symptom variation, as opposed to at two time points.

But yes, I don’t think for a lot of these patients, those are true co-morbid disorders, I think they are fluctuations that occur during the ED tragectory, and change when ED-symptoms change (ie, period of AN results in high OCD-like and anxiety symptoms, period of BN, in substance abuse, impulsivity). Or, they go hand in hand together (stress –> impulsive behaviours + BN, in a super simplistic example).

I was really surprised that “schizophrenia was three times more prevalent in AN-R (two times in AN-BP) than in other EDs.”

As a mental health worker I should really know better, but I just never really thought much about the co-morbidity of EDs and schizophrenia.

Your posts are always informed and thought-prevoking. Thanks for sharing, and keep up the awesome work!

Yes, me too! What’s interesting is that this finding is replicated in males with anorexia as well! (see next post). It is indeed interesting. But, I wonder, again as Saren pointed out, how much is this finding the result of malnutrition? Conversely, what if the AN was just the result of schizophrenia (paranoia about food, being poisoned?). I recall a scary moment, when I was underweight, when I stepped on the scale at the Hospital, and didn’t believe the number. My initial reaction was: it is a lie, they rigged the scale (because my sense of my physical body was so warped). So, I wonder. I think we have to be careful here, in teasing out what’s truly co-morbid, what’s just symptom overlap or malnutrition, what causes or leads to what, etc.

Thanks! I’m really enjoying doing this, it is very fun.

I know this is a bit of an old post to comment on, but it was very interesting. I developed psychotic symptoms when I was very malnourished, and my psych continues to keep me on anti-psychotics because he thinks I might be vulnerable to some psychotic disorder. I’m convinced that it was the result of malnutrition, as I’ve only ever had psychotic symptoms when in a starved state. I wonder whether this could be true of other people as well. It’s so hard to tease out co-morbid issues in an acutely ill state.

I would not be surprised that psychosis was malnutrition-induced in some way for you. There are lots of possible explanations that spring to mind. Of course, I don’t know if any of them are what actually happened, but it is (in my opinion/from what I know), feasible that it was malnutrition-induced. For example, low thiamine or even just hypoglycemia (which can produce psychotic-like symptoms)? I have no idea whether it is true for others as well, and if so, to what extent. (I do think the values in some of these studies for co-morbidity rates are way too high.)

I found this just googling around: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2972468/

It is definitely hard to tease out co-morbidity (or much else, for that matter) in the acutely ill state.

That was shocking. I knew it was serious, but I didn’t know a lot of those played into each other.