In 2009, Dr. Walter Kaye and colleagues published an article in the prestigious journal, Nature Neuroscience Reviews, titled “New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa”. [By anorexia nervosa, Kaye et al. limited themselves to restricting-type anorexics (AN-R), so some but not all findings may extend to bingeing-purging anorexics and bulimics] This review, which is lengthy and will take me a few posts to cover thoroughly, focuses on the “findings from pharmacological, behavioural and neuroimaging studies that contribute to the understanding of appetite regulation, reward, neurotransmitters and neurocircuits that are associated with AN.”

A striking feature of anorexia nervosa is the incredibly uniformity of traits and symptoms that patients experience, as well as the narrow range of onset. While the course of the illness varies from person to person, during the AN-R state, individuals exhibit very stereotypic presentation (and that, of course, may be due to malnutrition or common predisposing factors.)

Individuals with AN have an ego-syntonic resistance to eating and a powerful pursuit of weight loss…. they are often resistant to treatment and lack insight regarding the seriousness of the medical consequences of the disorder [not necessarily the presence disorder itself].

One of the biggest challenges in studying the etiology (causes) of anorexia is determining what components are predisposing traits (the result of genetic and epigenetic factors, and environmental influences) and what are state-related alterations (the result of malnutrition). Keep in mind, environment means everything other than the genetic and epigenetic changes one has inherited; the mother’s nutritional status during pregnancy, for example, is part of the environment. State-related changes are just as important as predisposing factors (traits) because they may play a role in sustaining and even exacerbating the illness.

What do we know about predisposing factors and state-related changes?

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

You’ve likely heard that eating disorders are highly heritable disorders, with an often quoted heritability of around 70% (Kaye et al. cite 50-80%, based on large, community-based twin studies). That is often misinterpreted to mean that genes account for 70% of anorexia or bulimia; that you can blame genetics for 70% of your ED and 30% on everything else. That’s wrong.

Heritability is a complex topic, but here is a list that will hopefully clarify things a bit. (I am reposting this, and will likely do so in the future, as it is an important but often misunderstood concept.)

- Heritability and environmentability are abstract concepts. No matter what the numbers are, heritability estimates tell us nothing about the specific genes that contribute to a trait…

- Heritability and environmentability are population concepts. They tell us nothing about an individual. A heritability of .40 informs us that, on average, about 40% of the individual differences that we observe in, say, shyness may in some way be attributable to genetic individual difference. It does NOT mean that 40% of any person’s shyness is due to his/her genes and the other 60% is due to his/her environment.

- Heritability depends on the range of typical environments in the population that is studied. If the environment of the population is fairly uniform, then heritability may be high, but if the range of environmental differences is very large, then heritability may be low…

- Heritability is no cause for therapeutic nihilism. Because heritability depends on the range of typical environments in the population studied, it tells us little about the extreme environmental interventions used in some therapies.

Some other things to remember (Visscher et al., 2008):

(Phenotype: the set of observable characteristics of an individual resulting from the interaction of its genotype with the environment.)

- Heritability is NOT the proportion of a phenotype (observable characteristics) passed on to the next generation: Genes are passed on (1/2 from each parent, and the half is unique to each offspring) not phenotypes

- High heritability DOES NOT MEAN genetic determination: It means that the majority of the variation that we see in a given trait (for example, perfectionism) between people in the population is caused by variation in genes/gene combinations among these people.

- Low heritability DOES NOT MEAN genetics are largely unimportant: It means that all the variation in the genes doesn’t account for much variation that we see in the observed behaviour/characteristic. There might be a lot of variance in genes that contribute though, it is just that environment plays a larger role (this is important, because in a different environment, this same genetic variation may play a larger role in determining the variation in the observed trait).

- Large heritability DOES NOT MEAN genes of large effect: In order words, we can’t determine the number of genes or their relative importance to a particular trait, from the heritability value. It may be a few, really important genes, or many, many genes that contribute a bit to the observed variation in the phenotype.

This last point is important: in eating disorders, the high heritability value might come from many, many genes that influence a plethora of different traits (phenotypes). Kaye et al. list some: “disordered eating attitudes, weight preoccupation, dissatisfaction with weight/shape, dietary restraint, binge eating and self-induced vomiting, and significant familiality of subthreshold EDs.” Heritable traits that seem to predispose individuals to AN and persist after recovery include: negative emotionality, perfectionism, harm avoidance, obsessive-compulsive personality traits, altered interoceptive awareness and others.

Keep in mind, of course, that no one of these traits is necessary for AN, and just a few of them may be sufficient to predispose someone to develop an ED during adolescence. Some sufferers might have a bit of all of those traits, while others may one or two of them (but they may be extreme). Likewise, for some, environmental factors might play a big role, for others, not so much.

Perhaps someone with a lot of family history of OCD, anxiety, perfectionism, etc.. might be pushed over toward anorexia with just a few negative experiences during adolescence, whereas someone with mild negative emotionality and harm avoidance (for example) might have to be faced with a lot of stressful experiences in order to develop an ED.

STATE-RELATED CHANGES

Starvation and chronic malnutrition has huge effects on the brain and the body. It changes the way one thinks and the way one’s body functions; it affects much more than just your libido. These changes may, and likely do, exacerbate and prolong the illness. (And that might be another reason recovery is so damn hard.) State-related changes, unlike predisposing trait, normalize (return to normal) after recovery. Examples of these for AN include: a reduction in brain volume, altered metabolism in the frontal, cingulate and parietal lobes and “regression to pre-pubertal gonadal function”. (Click here for a simple but neat Interactive Brain with some basic functional neuronatomy to get an idea of what those brain regions “do”.)

There are also endocrine and metabolic changes that occur as a result of starvation, namely altered concentrations of hormones and peptides that influence food intake and satiety, including neuropeptide Y, leptin, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), cholecystokinin, beta-endorphin and pancreatic polypeptide. This, of course, makes sense. And you might wonder, who cares? Anorexia is a brain problem, not a stomach problem. Kaye et al. would agree, but the GI system (controlled by the enteric nervous system and part of the autonomic nervous system) is very well-connected to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord). There is even a field called neurogastroenterology which focuses on the “brain-gut-axis”.

Kaye, Fudge and Paulus:

such alterations are likely to cause alterations in mood, cognitive function, impulse control and autonomic and hormonal systems, which indicates that they might contribute to the behavioural symptoms associated with the ill state… CRH administration in experimental animals produces many of the physiological and behavioural changes associated with AN, including hypothalamic hypogonadism, altered emotionality, decreased sexual activity, hyperactivity and decreased feeding behaviour. Therefore, it can be argued that some secondary changes in peptide concentrations can sustain AN behaviours by driving a desire for more dieting and weight loss. Moreover, malnutrition-associated alterations exaggerate emotional dysregulation…

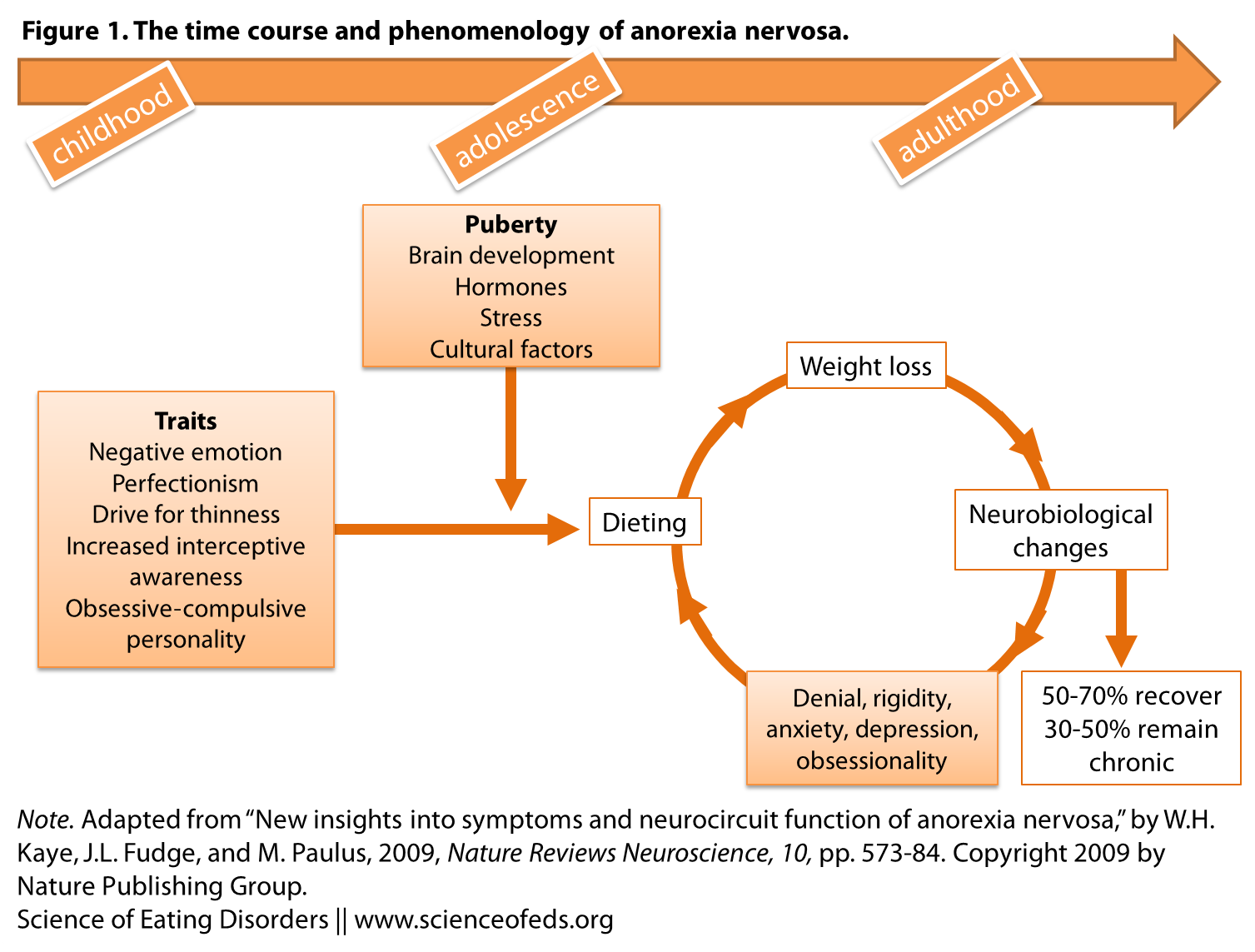

The figure below illustrates how the combination of traits (predisposing heritable factors), environmental factors (stress, culture) and state-related changes are the result of weight-loss due (due to dieting, for example) can result in the development and maintenance of this disorder (resulting in chronic illness for a notable percentage of individuals. (Keep in mind, this review focuses on restricting-type AN only, particularly those that have not experienced diagnostic crossover within the first 5 years of diagnosis.)

So how do we know whether the symptoms in AN patients are due to state-related changes (starvation) or stable traits that likely predisposed them to develop AN in the first place? It is a tricky question for researchers, and “a major confound in the research of this disorder,” according to Kaye and colleagues. Nonetheless, they end this first section of the review article with this:

…. studies have described temperament and character traits that still persist after long-term recovery from AN, such as negative emotionality, harm avoidance, perfectionism, desire for thinness and mild dietary preoccupation. It is possible that such persistent symptoms are ‘scars’ caused by chronic malnutrition. However, the fact that such behaviours are similar to those described for children who will develop AN argues that they reflect underlying traits that contribute to the pathogenesis of this disorder…

In upcoming posts I’ll summarize the rest of the review article (which includes a section on the neurobiology and behaviour and on the neurocircuitry of appetite).

Also, read this short and great post about the findings summarized in this review on the Brain Posts blog, written by Dr. William Yates. Check out his blog while you are there. His posts are shorter and more concise than mine, and his blog has a much broader focus.

References

Kaye, W.H., Fudge, J.L., & Paulus, M. (2009). New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10 (8), 573-84 PMID: 19603056

Please forgive me if I misread, but didn’t Dr. William Yates say on his blog that anorexia nervosa restricting subtype is more serious (on a biological level) than purging subtype or bulimia nervosa? :/

Sarah, where did Dr. Yates say that, and also, is this with regard to my statement that some findings may extend to AN-BP, BN?

I’m not sure what “more serious on a biological level” means. What do you mean?

Also – no need to apologize, even if you did misread!

lol he does the thing in psychology blogs where they put a picture of a bear next to an article about ocd XD

http://brainposts.blogspot.ca/2010/03/course-and-outcome-in-eating-disorders.html

The authors of the study concluded: “The outlook for patients with eating disorders suggests reasons for optimism for both patients seeking treatment and the clinicians treating them, particularly for patients seen in outpatient settings.” However, this was not true for women requiring inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. This group appears more chronic and treatment resistant. Additional treatment development and research is necessary for this more seriously ill population.

and

http://brainposts.blogspot.ca/2011/03/cognitive-biomarkers-in-eating.html

‘This model proposes that anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype is the most severe category of the eating disorders with bulimia nervosa being the least severe (on a general basis, it is possible for some individuals with bulimia nervosa to have a more severe eating disorder than some individuals with anorexia nervosa, restricting subtype). The data from this study indicate the anorexia nervosa restricting subtype demonstrated the most severe neurocognitive impairment with bulimia nervosa the least impairment.’