Most people hate starving, hate prolonged hunger and suck at dieting. Patients with anorexia nervosa (AN), on the other hand, excel in these areas. How can someone like being hungry? How are they able to exert such “self-control” (as many non-ED people often say) over their food intake? Part of the answer might lie with serotonin. But don’t worry, there’s no “chemical imbalance” – it is much more complex than that.

In this post, I’m going to continue discussing the review article in Nature Neuroscience (2009) by Kaye et al., focusing on what is currently known or hypothesized about the role of serotonin in anorexia (reminder, findings Kaye et al focuses are specific to restricting-type AN and may not apply to AN-BP or BN).

BUT FIRST, A LITTLE NEUROSCIENCE

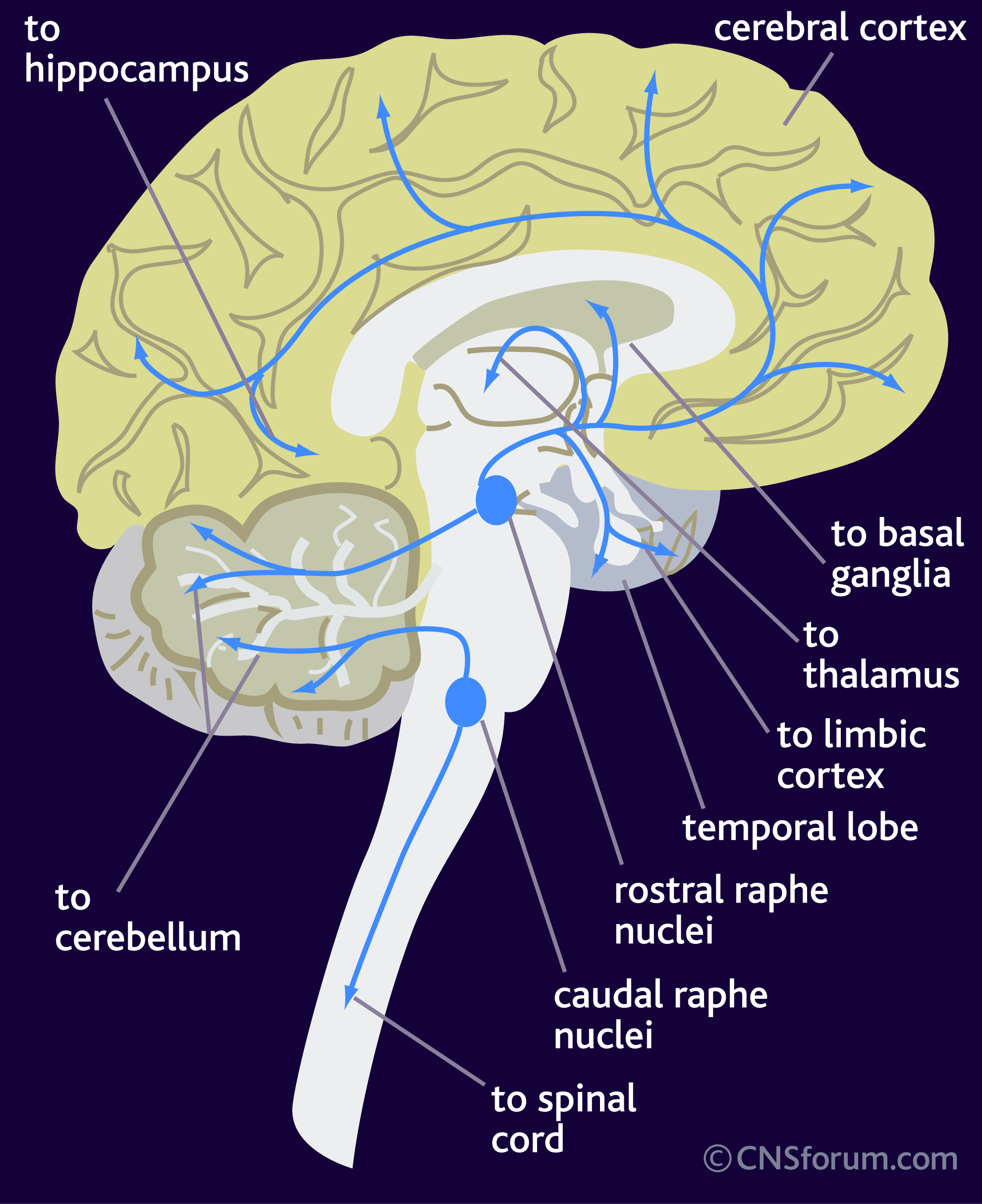

Serotonin (aka 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) is a neurotransmitter, meaning that it is a chemical messenger that cells in the brain use to communicate with one another. Neurons that make and release serotonin are located in a region called the raphe nucleus. These neurons project and “connect” to a variety of regions in the brain:

But this is where things start to get complicated. Thanks to clever marketing and sloppy science journalism, non-neuroscientists typically think that it is dopamine or serotonin or some other neurotransmitter, that’s responsible for making you feel happy, sad, anxious, depressed or what have you. Its release from a neuron is all that’s required for the behavioural effect.

Nope. Simply not true.

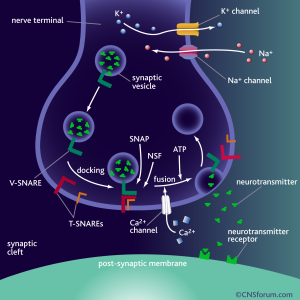

For a neurotransmitter to have some kind of effect, it has to be released from a neuron (called pre-synaptic neuron), transverse the synaptic cleft (a tiny space between two neurons) and bind to its receptor on the post-synaptic neuron. Released from neuron A and bind to its specific receptor on neuron B. Not just any receptor, but a receptor that recognizes this molecule. There is a serotonin receptor for serotonin, a dopamine receptor for dopamine, and so on.

Binding of the neurotransmitter to the receptor can lead to changes in what genes are turned “on” or “off” and the excitability of the cell (how easy it is to make it fire and send a signal?), among other things. It is the binding and the activation of the receptor and the pathways that lead to changes in what genes are turned “on” or “off”, and so on, that actually results in the behavioural outcomes, such as feeling happy or sad.

Ah, but it gets worse:

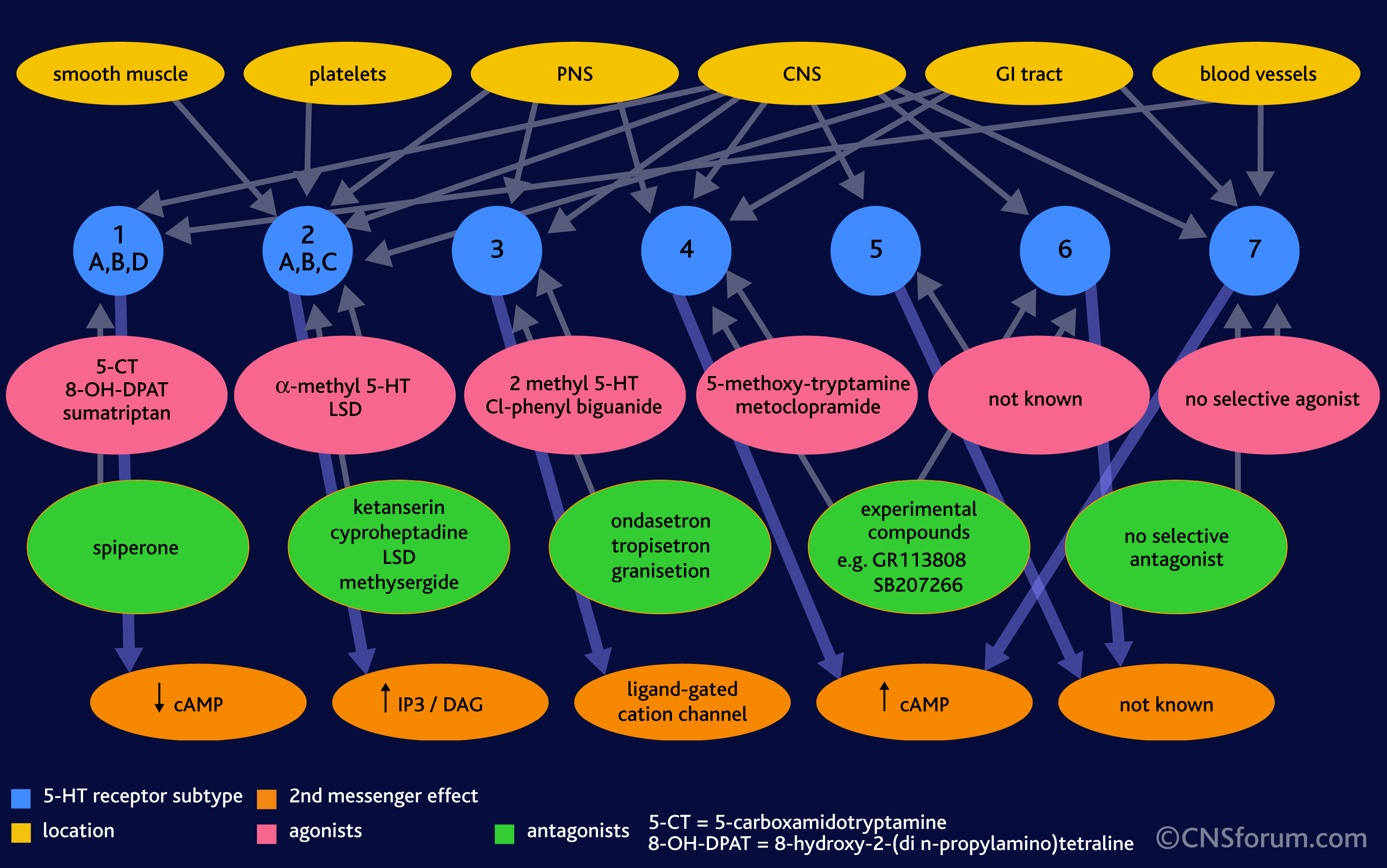

- there are *many* different kinds of receptors for each neurotransmitter (14+ for serotonin)

- they are expressed (or turned “on”) in different regions of the brain, some are only found in one area, some are found in an other, sometimes there is overlap

- a particular neuron might have several different kinds of serotonin receptors, and in different ratios

And even worse:

The effect of serotonin (and the end behavioural result or feeling) depends ENTIRELY on the receptor it binds to. Why? Because each receptor is different, it interacts with different proteins inside the cell, which can turn on or off different genes or change the properties of the cell, and many other things. One serotonin receptor can have a complete opposite effect than another receptor! Gives you a headache already, right?

In the image below, note that different cells and organs in the body (yellow/orange) have different serotonin receptors (blue), some have lots of different types, whereas other regions have only one or two. Note, too, that the effects on a cellular level of serotonin binding to these receptors is very different (red/orange). Different molecules are turned on and off.

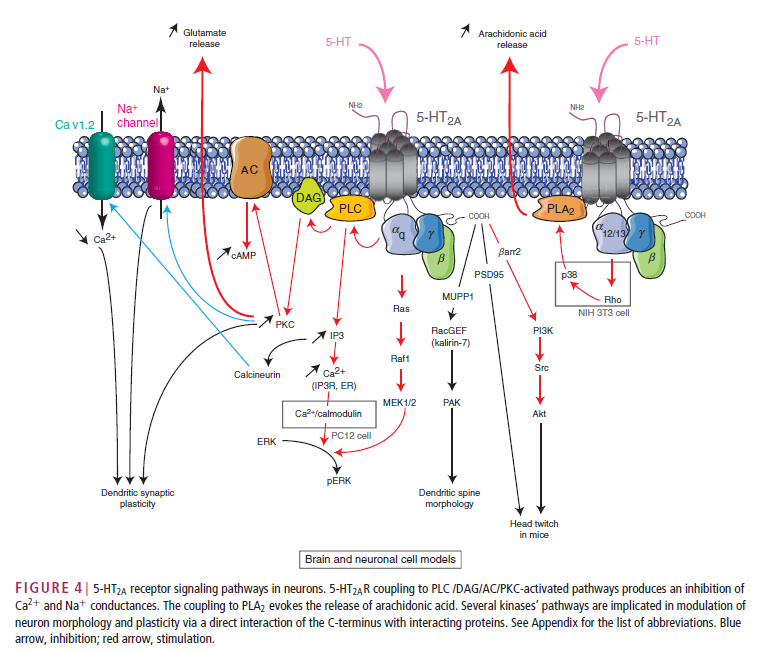

Actually, the picture is even more complex. There’s lots of stuff going on inside a cell once serotonin binds to a receptor. The picture below is just one example of what scientist think happens after serotonin (5-HT) binds to a receptor called 5-HT2A:

From: Masson, J., Emerit, M. B., Hamon, M. and Darmon, M. (2012), Serotonergic signaling: multiple effectors and pleiotropic effects. WIREs Membr Transp Signal, 1: 685–713. doi: 10.1002/wmts.50 (link)

In other words, the brain is complicated (as if you didn’t know that already). Adding to the complexity is that the neurotransmitter receptors on the cell membrane are in near-constant flux: the ratios of one serotonin receptor to another can change dramatically during development, but also throughout life, for example: in response to stress.

The brain is not static. And changing one thing can lead to a chain reaction – like removing or changing the size of a particular species in an ecosystem.

That means there’s no such thing as a “chemical imbalance”, because there is no such thing as a “chemical balance”.

The fact that the serotonin system is implicated in mediating some aspects of anorexia nervosa can mean alterations in all sorts of things: the amount of serotonin made, the amount of serotonin released, how well serotonin binds the receptor, what receptors are present and it what amounts, and much more..

I’ve mentioned before that it is difficult to tease apart whether some differences that scientists find are a cause or consequences of the disorder. Even studying patients after recovery and doing prospective studies (studying a large population before they get the disease/disorder you are interested in studying) doesn’t tell us the complete story. Keep this in mind when you read studies about eating disorders and other mental disorders in the popular press.

THE ANOREXIA NERVOSA BRAIN

The serotonergic system is involved in regulating feelings of satiety, impulse control, and mood (among many other things such as vasoconstriction, GI functions, nausea, and more).

A review paper I’ve discussed previously nicely summarized some interesting findings. When compared to healthy controls, individuals with AN had decreased 5-HT2A receptor density in some regions but increased 5-HT1A receptor density in others.

Kaye et al nicely summarizes what this might mean on a behavioural level:

“…People with anorexia nervosa (AN) enter a vicious cycle, whereby malnutrition and weight loss drive the desire for further restricted eating and emaciation” Why might that be?

“Evidence suggests that, compared with healthy individuals:

- individuals who are vulnerable to developing an eating disorder might have a trait [prior to eating disorder onset] for increased extracellular serotonin (5‑HT) concentrations and

- [a different ratio] in postsynaptic 5‑HT 1A and 5‑HT 2A receptor activity”

These two changes, together “might contribute to increased satiety and an anxious, harm‑avoidant temperament”

Gonadal steroid changes during menarche or stress related to adolescent individuation issues might further alter activity of the 5‑HT system and so exacerbate this temperament, resulting in a chronic dysphoric state.

It is important to note that food–mood relationships in AN are very different from those in healthy controls. That is, palatable foods in healthy subjects are associated with pleasure, and starvation is aversive. By contrast, palatable foods seem to be anxiogenic in AN, and starvation reduces dysphoric mood.”

So what happens when those with anorexia nervosa (or those prior to the full DSM-IV diagnosis, but on the way there) starve? or eat?

“In subjects with AN, starvation and weight loss result in

- reduced levels of [a serotonin metabolite] and inferentially reduced extracellular 5‑HT concentrations

- but exaggerated 5‑HT 1A receptor binding in limbic and cognitive cortical regions

Starvation‑induced reductions of extracelluar 5‑HT levels might result in reduced stimulation of postsynaptic 5‑HT 1A and 5‑HT 2A receptors, and thus decreased dysphoric symptoms.

However, when individuals with AN are forced to eat, the resulting increase in extracellular 5‑HT levels, and thus stimulation of postsynaptic 5‑HT 1A and 5‑HT 2A receptors, increases dysphoric mood, which makes eating and weight gain aversive…”

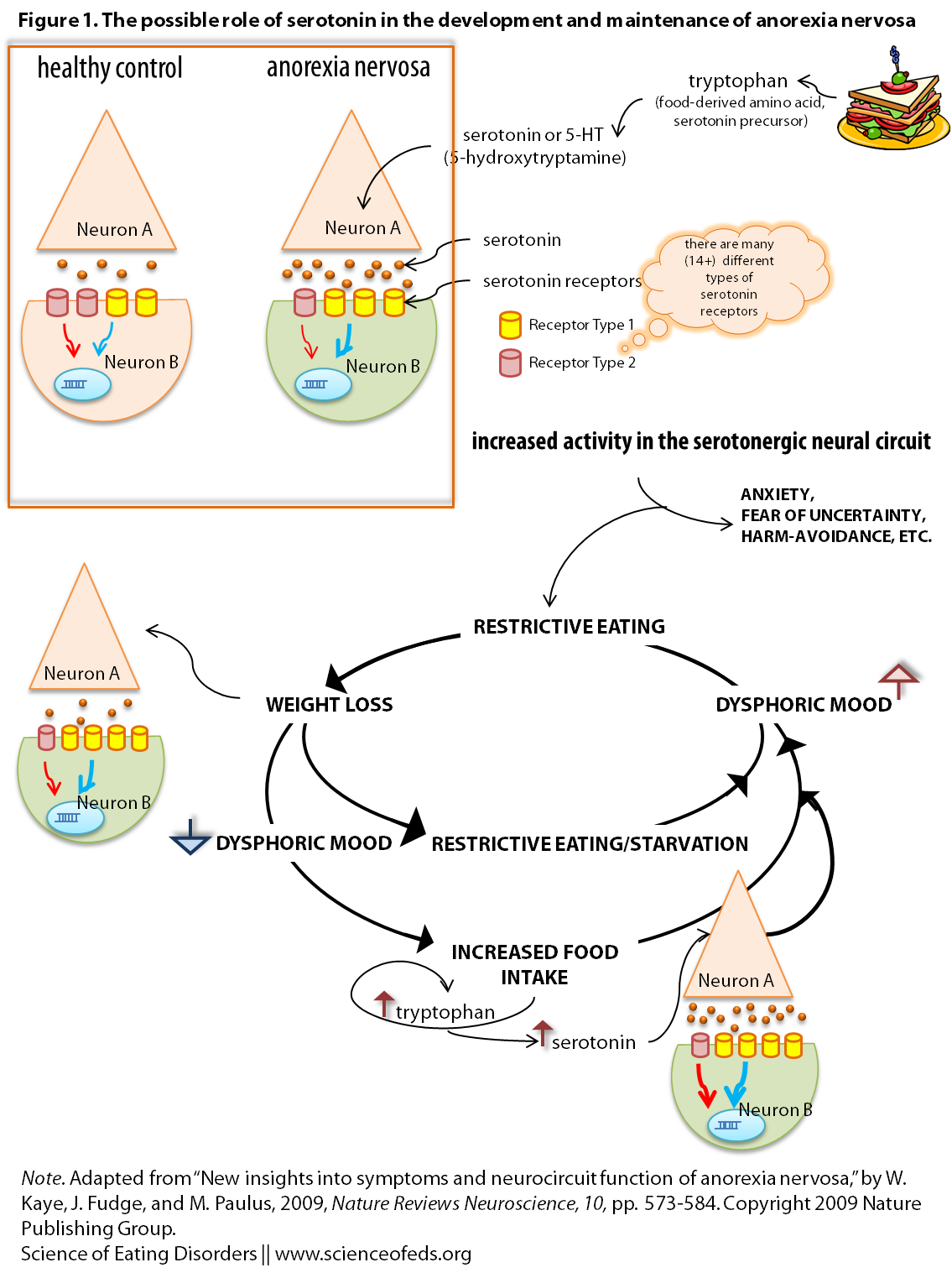

I adapted a figure from Kaye et al (Figure 2) for the purpose of this post, see the image below. It is a graphical representation of the hypothesized role of serotonin in mediating some aspects of anorexia nervosa.

Feel free to ask me any questions if it is confusing, but here’s the run down:

- Tryptophan is an amino acid found in food, and a precursor to serotonin.

- Patients with AN have an “overdrive” in the serotonin system, producing/releasing more serotonin, as well as a different ratio of two receptors on the receiving end (the post-synaptic neuron, “Neuron B”)

- This overdrive leads to higher anxiety and harm-avoidant traits.

- Reducing caloric intake results in less tryptophan, and thus, less serotonin being made. This reduces the feelings that resulted from an overdrive of the serotonin system (anxiety, harm-avoidant temperament, etc..)

- BUT, the nervous system is not static. It adapts to a reduced intake and compensates.

- It compensates by putting MORE receptors on the post-synaptic neuron (Neuron B), so that there are more chances and opportunities for the limited serotonin released, to bind.

- Given these changes, when an individual with anorexia nervosa eats: suddenly there is more tryptophan and thus serotonin in the system, it leads to EVEN more anxiety. Because now, there’s lots of serotonin, but there are also a LOT of receptors on “Neuron B”, and the more receptors serotonin binds to, the more changes occur that in the end may lead to heightened anxiety, harm-avoidance, etc…

- OR, if they continue restricting: changes in the neuropeptide systems (increase in stress-hormones for example, and many other things) drive restriction FURTHER, and contribute to changes in behaviour and cognition (prolonged starvation definitely changes the way one views themselves and the world),

- This of course, perpetuates the cycle. Leading to MORE restriction, and so on..

Of course, many recover: just as the system can adapt to less food, and thus less overall serotonin, it can adapt to increased serotonin and remove some of the extra receptors on the cell membrane (in Neuron B, in our example). One must remember: the brain is NOT static.

Why do we think that more serotonin leads to behavioural traits commonly seen in AN? And, is it fair to make that assumption, as it underlies the entire argument?

Moreover, imaging studies provide insight into how disturbed 5-HT function is related to dysphoric mood in AN. That is, PET imaging studies show striking and consistent positive correlations between the binding potential of both 5-HT 1A and 5-HT 2A receptors and harm avoidance — a multifaceted temperament trait that contains elements of anxiety, inhibition, and inflexibility. Studies in animals and healthy humans support the possibility that 5-HT 1A and 5-HT 2A receptor activity has a role in anxiety.

Furthermore,

Importantly, experimental manipulations that reduce the levels of tryptophan in the brain decrease anxiety in both ill and recovered AN subjects.

So what’s the take home message? (This, too, is really, really simplified)

Alterations in the serotonergic system (too much serotonin/5-HT, a different ratio of receptors) leads to increased “anxiety, inhibition, inflexibility”. [Patients with anorexia nervosa], by reducing their caloric intake, reduce the anxiety and dysphoria associated with the serotonin system overdrive, by decreasing tryptophan intake (precursor to serotonin, food-derived amino acid). Compensatory changes in the nervous system due to starvation lead to an even bigger overdrive when the AN patients are forced to eat (exaggerating the dysphoric mood).

Thus, individuals with AN might pursue starvation in an attempt to avoid the dysphoric consequences of eating and consequently spiral out of control.

References

Pietrini, F., Castellini, G., Ricca, V., Polito, C., Pupi, A., & Faravelli, C. (2011). Functional neuroimaging in anorexia nervosa: A clinical approach European Psychiatry, 26 (3), 176-182 DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.07.011

Kaye, W., Fudge, J., & Paulus, M. (2009). New insights into symptoms and neurocircuit function of anorexia nervosa Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10 (8), 573-584 DOI: 10.1038/nrn2682

Tetyana, have you found that there are more research studies done specifically about anorexia than bulimia? A friend of mine posted in response to one of your posts and mentioned in passing how, with her diagnosis of AN b/p, she identifies most strongly with AN personality traits, etc. I have the same diagnosis but identify heavily with the bulimic side of things (though I do identify with both, I’d say I fit MORE in the bulimic category). So while I love love love your blog and find it interesting on so many levels, I wonder if you’ve read any studies on Bulimia (apart from the correlation between bulimic behavior and impulsivity); maybe about what in the brain is affected? I’ve heard (though I can’t remember where) that dopamine seems to be more of a factor in bulimia than anorexia. Do you know anything about this?

SB: my gist of things is that there is more research on AN-R, because it is easier to do, in the sense that your study group is more homogenous and it is easier to control, in that sense. That’s harder in AN-BP or BN – given that there is a lot of crossover, for these diagnoses. That makes it harder to study and to really figure out what the data you get means. Do you know what I mean? Often times studies focus on AN patients either really early on in the disorder, or those who haven’t crossed over to another diagnosis in 5 years (when their chance of doing so markedly decreases). And it could also be because AN was ‘identified’ earlier and perhaps it is viewed as a more legitimate problem? At least it was known to the medical and research community earlier than BN – as far as I understand.

I will blog more about bulimia, for sure. And yes, I’ve read tons of studies :-), it is just often difficult picking one to write about. And, I’ve only been doing this for less than 4 month (30 posts so far), so there’s so much more that I want to and need to cover. Way more! But yes, thank you for that request – I’ll definitely try to find a good paper on neurobiology of BN.

This was such an interesting read! I love science so much, and I love that you’re promoting using science to better explain EDs! In the time leading up to my diagnosis (EDNOS), nobody really understood what I meant when I told them I got a euphoria, or even, “high,” off of starving, and that eating made me depressed. I’ve never been worried about my weight (I’ve always been naturally skinny), but I love the feeling I get from restricting. Which sounds terrible when I type it out :/ eep!

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed the post! I totally get you on the hunger high. I just make sure I never (or, well, rarely since it is never 100% preventable) go too long without eating, because things can tumble down pretty quickly.

This is so fascinating! But I’m left wondering how to correct the problem – particularly if there is a way to help deal with the serotonin system overdrive that hits hard during refeeding after prolonged starvation. Any ideas?

Good question! Outside of just powering through it, I’m not sure. I don’t know if anyone has an answer to that, to be honest (but I also can’t say I looked thoroughly for an answer). Ultimately, it will suck: Eating more will be anxiety-inducing and crappy, but after a while that will (hopefully) subside. I’m not sure what would make the process easier though.

Some patients have found that avoiding/limiting foods high in tryptophan (which is difficult, I must add), can help.

Also, using pharmacological therapy, you can try and “break” the habit of feeling excessively anxious regarding food intake. With your doctor, you can develop a plan to help condition your mind and body to be able to at least CONTROL those feels of anxiety…the same way someone with a phobia of social situations or other intense fears can eventually learn to live with them.

The fears, thoughts, and feelings may never leave but they don’t have to control you… You can learn to control them.

Thanks for a great article Tetyana.

(P.S. Experience: PhD in neuroscience and cognitive psychology; life coach for ED/addiction patients; former AN patient now 5 years in recovery.)

Hello, very interesting, correct me if I’m wrong, but if serotonin causes the anxiety symptoms, why are so many ED patients prescribed SSRI’s? won’t this just make referring more difficult and anxiety provoking?

Yes, but many ED patients are also suffering from depression and its generally helpful to initially try and “lift” the person out of such depression (old school thoughts).

However, this is also the reason why many patients become non-compliant with their SSRI medications…especially after they have been in some level of treatment for some time.

Many clinicians and neuroscientists (like myself) who study these behaviors now realize that in fact, there are other pharma. targets which are more helpful in treating the anxiety related to eating… many of these are the same drugs being used to help those suffering from PTSD. Anti-anxiety drugs are thus becoming a a more common and more effective method of pharmacological interventions.