The approaches used in clinical practice to treat patients often lag behind the most up-to-date developments in research. It can take a long time to integrate scientific findings into clinical practice. This, of course, is not limited to eating disorders or even mental health issues. This so-called “science-practice gap” exists for many reasons, which vary depending on the medical discipline.

This issue, though, seems particularly bad when it comes to eating disorder treatment.

There’s the issue of conducting good studies – how do we determine what is efficacious? That’s a complicated task. What is “recovery” and how long is long-enough for follow-up? Is what we consider to be efficacious really efficacious or just slightly better than the rest?

Then there’s the training: mental health seems to be undervalued in medical school curricula for one, but even more importantly: “Clinicians tend to give more weight to their personal experiences than to science when making treatment decision.” And can’t you really blame them, most of us tend to stick to what we know and to doing things the way we were initially taught.

Wallace and von Ranson wanted to examine this “research-practice gap” among professionals who use various psychotherapies to treat eating disorder patients. They surveyed 402 members of two international eating disorder organizations (one open to clinicians/therapists and researchers and the other is exclusive to researchers) using an on-line survey.

The research-practice gap refers to a division of experts in the field of mental health into two groups – those who engage in research and those who engage in practice – that often hold different perceptions concerning the importance of research and clinical experience in providing the basis for best practice… This study surveyed ED professionals involved in research, practice, and both, allowing for direct comparison of the perceptions of each group.

Wallace & von Ranson used the American Psychological Association’s criteria for determining whether a therapy was empirically-supported (“probably efficacious treatment”):

According to these criteria, one of the three following conditions must be satisfied: (1) two experiments must demonstrate that the treatment is more effective than a waiting-list control group; (2) one or more experiments must demonstrate superior outcome to a pill, psychological placebo, or another treatment, or demonstrate equivalent outcome to an already established treatment in experiments with adequate statistical power; or (3) a series of single case design experiments (n > 3) with good experimental design must demonstrate efficacy in comparison to another treatment.

Survey responders:

- 80% female, 54.7% less than 45 years old

- 3/5th worked or went to school in the US, 15% in Canada, and the rest in other countries around the world

- On average, researchers (whether researchers or clinician-scientists), spent around 12 years doing research (including training)

- For clinicians and clinician-scientists, there was an average of almost 15 years in clinical practice (including training).

- 63% had degrees beyond a master’s level (MD, PhD, PsyD), 31% had a master’s dergee whereas 7% had a diploma/associate’s degree, etc..

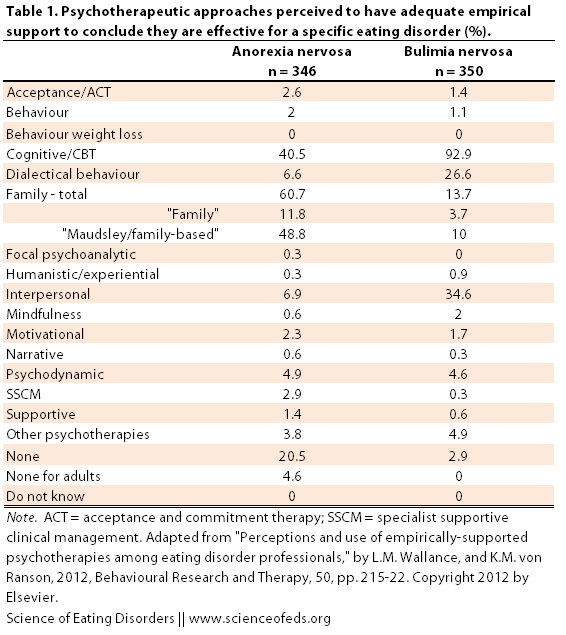

First, they “were asked to indicate which psychotherapies they perceived ‘to have adequate empirical support to conclude that they are effective’ for the treatment of each eating disorder. The results are shown below in Table 1. I highlighted some interesting results:

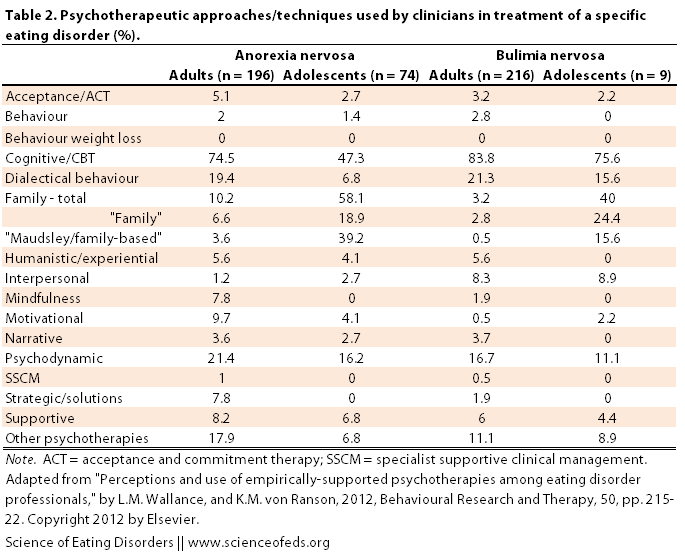

Then they “were asked to indicate the psychotherapeutic approach(es) they had provided to their most recent client with each ED.” Table 2, below, illustrates the results to this question. Again, I highlighted some numbers that seemed interesting to me, particularly the differences between adults and adolescents and between different disorders. Interestingly, about half said that they used more than one approach with their client: “AN (53.0%, n=143), BN (48.1%, n=126), and BED (46.1%, n=76)”.

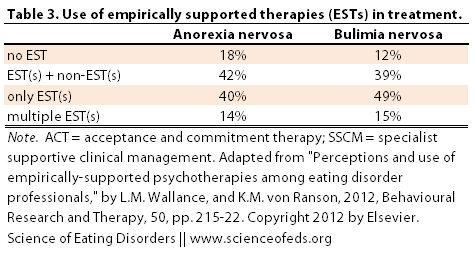

You can also organize the data in another way, based on whether the treatment individuals provided was empirically-supported or not. Wallace & von Ranson did not provide a table for this, so I organized the information in a table (below). They categorized the responses into those that provide only non-empirically-supported treatment (EST), a combination of EST and non-EST, or only EST. And of those providing only EST, how many provide more than one EST.

RESEARCH-PRACTICE GAP

Wallace and von Ranson then compared the perception of whether a psychotherapy was an EST between researchers, research-clinicians and clinicians. They found no significant differences between researchers and research-clinicians, but there was a difference between those involved in research and those exclusively in clinical practice.

Overall, there were few consistent differences in perceptions of ESTs between groups. Where significant differences arose, researchers/researcher-clinicians tended to be more likely than clinicians to perceive ESTs as having adequate empirical support…The opposite tendency appeared in regards to non-ESTs: clinicians were more likely than researchers/researcher-clinicians to have inaccurately endorsed non-ESTs as ESTs.

Overall, the perceptions the participants of the survey had with regard to correctly identifying ESTs and non-ESTs was good:

When participants were asked to identify psychotherapies that they perceived to be ESTs, more than 90% and 75% indicated CBT for BN and BED, respectively, and almost two-thirds indicated family therapy for AN. Thus, most agreed that at least one specific psychotherapy for each ED was an EST. However, there were considerable differences in perceptions in the large variety of additional psychotherapies – some with empirical support, some without – that a minority of participants perceived to be ESTs.

Wallace and von Ranson suggest increasing the efforts to provide clinicians’ with the latest information on empirically-supported psychotherapies as well as improving training and providing continuing education courses to “ensure that professionals remain informed of recent research developments”.

The good news is that a majority of survey-responders did use an EST in the treatment of EDs (82% for AN, 88% for BN and BED). But, Wallace and von Ranson report that a lot of the time, it wasn’t “implemented” in the same way that was studied in research trails, and it was often used in combination with non-ESTs. This, of course, makes it difficult to assess whether the treatment provided was actually as beneficial as research trials suggest.

An interesting point was raised in the discussion:

Considering the range in the number of psychotherapeutic approaches some participants used (i.e., up to five approaches provided to a single client), some psychotherapies were likely provided simultaneously, in combination. As a considerable portion of individuals with EDs fail to improve adequately with even the most effective psychotherapies, combining psychotherapeutic approaches might result in more efficacious treatment.

However, considering the current climate of managed healthcare, wherein the number of sessions provided to a client is often limited, use of multiple psychotherapies likely limits scope of each psychotherapy provided. Furthermore, risks of combining psychotherapies – even those that are individually efficacious – must be recognized. For example, combining psychotherapies may dilute essential mechanisms and targets of change of each treatment, and may not be conceptually and/or procedurally compatible.

In my opinion, these points illustrate really well why studying the effectiveness of a given treatment is really difficult. One can use this data and argue that, oh, clinicians, as a whole, are misinformed about which treatments have empirical support and which don’t, and given that they are more likely to provide treatment they themselves think is empirically supported, they are not providing the best possible treatment.

Maybe.

But, it is also true that findings from treatment studies, particularly for very complex mental health disorders are difficult to assess. Sure, you can split ED patients into AN, BN and BED, but I’d argue AN-binge/purging subtype can be more similar to BN than AN-restricting type, for some individuals. My point here is these demarcations between anorexia subtypes and bulimia are rather arbitrary, and I think combining restricting and binge/purging anorexics into one group is not ideal for these studies. But then again, diagnostic crossover is really common.

And then there are the points I raised earlier: what’s a long-enough follow-up time? What is “recovery”? Do the studies consider what the patients themselves want to achieve? Maybe they didn’t recover by the researchers standards, but they are happy with their progress? I suspect I’d fall into that category a lot if I was enrolled in a study. I had periods where I would fit into the DSM-IV category for AN, but, mentally, it was one of the healthiest times in the last 9 years (no over-exercise, no obsession with food or weight, eating 3 meals with snacks, going out to eat, etc.. my weight was just low because I wasn’t binging and purging at all). Based on metrics, I’d fail, but, in my world, I was ecstatic: I was free from bulimic symptoms, I was free of the obsession with numbers, the anxiety over weight and calories. It was phenomenal.

I’m sure I’m not alone here.

So, you can make the argument that, maybe clinicians that aren’t using what Wallace & von Ranson consider to be an EST, are using psychotherapies that are actually more beneficial and helpful for their clients.

Of course, this makes things really complex. Particularly if you are in search of a therapist or psychiatrist, or are the parent/care-giver of someone who is in need of psychotherapy. How do you know what approach to take? How do you know, even if the therapist is using CBT, that it is the same CBT that has been evaluated in treatment studies?

Hard questions, for which, I don’t have any answers, unfortunately. I don’t know.

One thing I was wondering when reading this paper was how the results would look if you sorted it based on the level of training that survey participants had.

One really important point to keep in mind with regard to the findings in this paper:

“We used the APA’s criteria for a “probably efficacious treatment” (Chambless et al., 1996) to identify ESTs, which is only one of various sets of criteria developed to identify ESTs (see Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Using alternative criteria likely would have affected the findings.”

Moreover, the authors had no knowledge of the clients, their ED histories, stage and duration of illness, psychiatric co-morbidities, family history, age, gender, sexual orientation and so on. That is another limiting factor that should be considered when reading this study.

They conclude by suggesting that: “increasing clinicians’ awareness of a range of research evidence, particularly regarding the variety of psychotherapies shown effective for a problem, may also help to close the research practice gap, as participants involved in research demonstrated more accurate awareness of a range of ESTs.”

[toggle title_open=”APPENDIX: What did they consider to be an EST in this study?” title_closed=”APPENDIX: What did they consider to be an EST in this study?” hide=”yes” border=”yes” style=”default” excerpt_length=”0″ read_more_text=”Read More” read_less_text=”Read Less” include_excerpt_html=”no”]

Anorexia Nervosa:

- Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT, for relapse prevention post weight-restoration)

- Focal psychoanalytic therapy

- Maudsley/family-based treatment

- Motivational interviewing

- Specialist supportive clinical management

Bulimia Nervosa:

- CBT

- Interpersonal psychotherapy

- Maudsley/family-based treatment

- Motivational enhancement therapy

Binge Eating Disorder:

- Behavioural weight loss

- CBT

- DBT (Dialectical behavioural therapy)

- Interpersonal psychotherapy

- Motivational interventions[/toggle]

I’m really curious to find out what you think about the findings in this paper? What psychotherapy treatments have you had and what do you think has worked for you?

What are your thoughts on how to integrate and make sense of the EST data with the findings in Eddy et al. papers (here and here) that illustrates the high rates of diagnostic crossover?

References

Wallace, L.M., & von Ranson, K.M. (2012). Perceptions and use of empirically-supported psychotherapies among eating disorder professionals. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50 (3), 215-22 PMID: 22342168