My previous post on the effectiveness of residential treatment centers (RTCs) generated a lot of discussion. A point that was raised several times, on the blog, on Facebook and other forums was the fact that there are risks in choosing an RTC for treatment.

Laura Collins did a great job of articulating some of the risks in her comment:

Among the risks: delaying necessary changes at home, disempowering or alienating relationships at home that are necessary for longterm health, exposure to behaviors and habits that had not been an issue previously, exposure to unhealthy relationships with other clients, an artificial environment that can’t translate to life after RTC, and therapeutic methods or beliefs that are false or don’t apply.

There risks are not specific to RTCs. They hold true for inpatient treatment, partial hospitalization and to a lesser extent, outpatient treatment. I thought it would be nice to explore in more depth some of the risks associated with treatment. If you are receiving treatment or are the caregiver of someone who is, hopefully this will help you in recognizing what to avoid and when to seek alternative treatment options.

Inadvertent effects that are associated with the treatment itself, whether it is due to medication or actions of the physician/healthcare provider, are called iatrogenic.

Also, if you are wondering about Part 1, you can check it out here: When Clinicians Do More Harm Than Good (Attitudes Toward Patients with Eating Disorders). (Check out the comments, too!) The title of that entry is self-explanatory and I never meant to do a follow-up, but the content of this article is relevant, and so I titled it “Part 2”.

In 2011, Dr. Janet Treasure and colleagues published a nice article exploring some of the iatrogenic factors that may perpetuate and maintain eating disorder behaviour. The paper was inspired in response to a carer’s concern that physicians may often hamper treatment.

DAMAGING BEHAVIOURS BY CLINICIANS (CARERS’ PERSPECTIVES):

- telling parents/carers that they caused the illness

- telling parents/carers that the patient is not “sick enough” and/or doesn’t need treatment

- keeping parents/carers out of the treatment process, telling them to “take a back seat”

- telling them they are sick because they are too ‘attached’, or due to ‘bad parenting’

- not educating parents/carers what to do once out of treatment

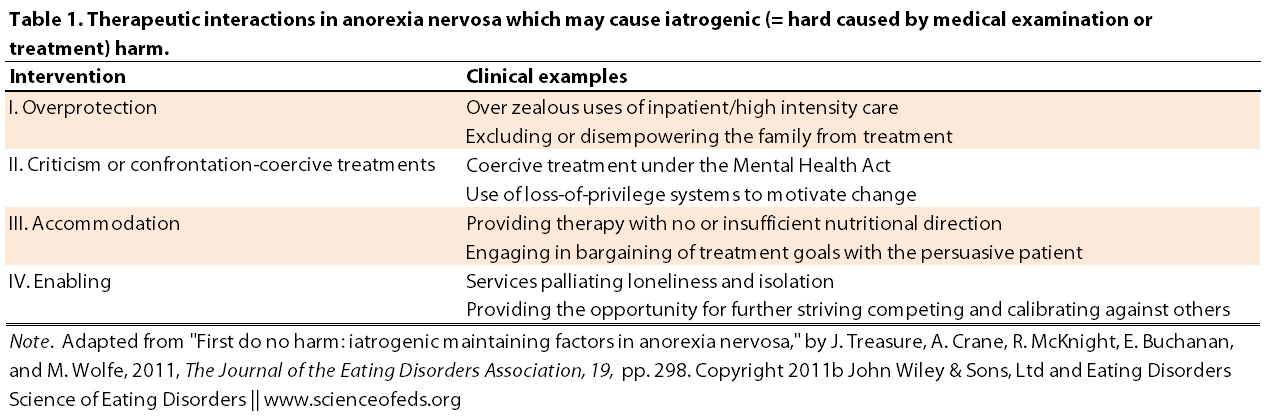

Treasure et al. summarize different “therapeutic interactions in AN that may cause iatrogenic harm” (see Table 3 below). The paper focuses particularly on anorexia but I think most – if not all – points apply to bulimia and EDNOS as well. Perhaps there are slight differences, but I do think there are more similarities than differences.

It is not uncommon for parents (and/or caregivers), upon learning about their child’s (or partner’s, friend’s, etc..) eating disorder, to react in a highly emotional and anxious manner. Although this reaction is almost to be expected, it may act to reinforce the eating disorder. Conversely, failure to act, choosing instead to accommodate behaviors (even unknowingly) may also perpetuate symptoms.

It is a tough stop to be in, no question. Knowing how to act and what to say to a patient with an eating disorder is difficult. In my personal opinion, I think age and length of ED history are among the most important factors in guiding what to say and do and when to do or say it.

Knowing what to do is really hard if not impossible. And doing the right thing can also be really hard. There is no recipe, no protocol, no guidebook on how to successfully care for someone with an eating disorder. (And by care, I mean help in the recovery process.) But there are common ways that parents, partners, caregivers and clinicians often fail. I’d bet usually because they just don’t know that their behaviours and attitudes end up being counterproductive.

Treasure organizes the risks into several categories: overprotection, criticism or confrontation-coercive treatments, accommodation and enabling.

I’ve made a point form summary of the points Treasure et al. raised for each category:

Overprotection

- rushing to utilize intensive treatment too early on and for too long

- inpatient environment can be unhelpful (and often the content and precise goals of treatment are unclear)

- environment is very controlled (i.e. no ability to practice normal eating habits in the “real world”)

- families and caregivers are often excluded from treatment which prevents them from learning how to provide support outside of the hospital/residential setting

- even if home environment is toxic, the ‘abrupt reintegration upon discharge” creates a whole set of other problems, particularly if there’s no step-down process.

Criticism or Confrontation-Coercive Treatments

- there is a need to maintain a calm, compassionate and respectful relations between the physician and the patient, otherwise, “an attitude of defiance, rebellion and lack of compliance with treatment” may arise, leading to a “me versus them” mentality

- “Restricted activities, chaperoned exercise, limited use of computers/cell phones and increased meal plans can seem like a punishment, especially where the reasoning behind them is not explained and the patient is not given the opportunity to express their views.”

- Motivational interviewing technique may be useful in cases where patients are unmotivated to change

Accommodation

- Accommodating the patients desire to delay weight gain and physical stabilization might enable the ED behaviours to become even more habitual and entrenched, protracting the recovery process

Enabling

- Prolonged inpatient stays may result in patients learning new behaviours or compete with other patients, delaying the recovery process

- This point is crucial, and one I’ve seen manystruggle with: “services can set up a vicious circle whereby the clinician or inpatient service provides the main social network…. the sufferer may feel compelled to ‘hang on’ to their illness in order to keep within the service loop.” (If you recover and you don’t need your “team”, then what?! This is made worse if outside contact is very limited.

- Often patients believe that in order to receive care, or the same level of support, they can’t recover and must remain sick. I’ve experienced this myself, feeling that I wasn’t ‘sick enough’, but wanting more help. Thankfully, as I’ve gotten older, that feeling has passed. I realize when I need help and I don’t hesitate to ask for it.

- A stepped-care approach is crucial in helping the patient reintegrate into the world outside of the ED

Treasure et al. raise several other points that should be taken into account during treatment.

Nutritional stabilization is a necessary and crucial step in the treatment of anorexia nervosa as well as bulimia nervosa. Refeeding in the case of anorexia is difficult and has to be done with care:

Frequently all the foods used to refeed become associated with weight gain. A fear is produced which can stop the person from feeling they can maintain their weight whilst eating these normal foods, or leads them to act out their anger and frustration by bingeing on the foods that they were forced to eat. Graded meal plans where foods like puddings and calorific drinks are added last, or do not feature in maintenance plans, again fuel these beliefs.

There’s another important point that Treasure points out that is particularly true for patients in inpatient and residential treatment: the stable, structured environment filled with routines and rules.

Sounds great, right? Most anorexics and those with a history of anorexia thrive in such an environment. I do.

In fact, as I’ve mentioned earlier, people in my life can probably readily observe when I’m entering a period characterized by bulimic behaviours: structure, routine, and stability fly out of the window. In my healthy state, I’m an organized and habit-loving person. Conversely, during my worst periods of anorexia, it was obsessive: a break from routine was catastrophic. Quite literally, it would make me incapable of focusing or doing anything.

Often the inpatient environment is highly structured with routine and rules pervading the day. This can be highly valued by those with an obsessive-compulsive temperament since it produces a sense of security, but on the downside allows the obsessive-compulsive traits to dominate. The nature of a daily inpatient routine with activities planned, meal times arranged and predictable menus leads to lack of practise in decision making involving everyday tasks. Additionally, such a rigid routine can lead to panic and distress when, in the ‘real world’ things do not run on time, plans are changed and portion sizes vary.

Of course, some routines are great. Learning to eat at normal times and training my body to be hungry at normal times of the day was very important. Going to bed and waking up at the same time was almost miraculous in its ability to extinguishing bulimic behaviors and chaotic eating.

But as I got more comfortable with it, I began performing experiments: what if I go to bed later (I’m at a concert, or at a friend’s party)? What if I eat lunch later, or earlier because of convenience? What if I don’t work out at that time, but at a different time? Sometimes those experiments went well, other times they didn’t.. and I learned something then, too.

Learning to be more flexible and generally more “chill” was very important to me. I would’ve thrived in a structured inpatient/residential environment and then fallen flat on my face upon discharge.

Treasure et al. also suggests that clinicians and families drop the “all-or-nothing” thinking about recovery. Patients can feel like they failed if they didn’t achieve recovery during a 3 month residential treatment stay, or after 20 sessions of CBT, for example. Feelings of failure can themselves lead to falling back into eating disorder behaviours. Viewing recovery as a process might be more beneficial in such cases.

Recovery is by nature a prolonged staged process and clinician and patient need to have nonperfectionist goals. Treatment needs to focus on developing flexibility, turning from detail to seeing the bigger picture and learning to cope with chaos.

Exactly. I really agree with this, particularly for patients who might not have an adequate support system, or have a long history of eating disorder behaviours.

Recovery is HARD. And I used to get really angry and mad at myself for not being recovered. I recall when I first started treatment at 14 I told myself: by the time I am 18, this bullshit has to stop. I thought, this is a waste of my time, I have better things to do than this. (Learning neuroscience, for one!)

At 18, however, I wasn’t recovered. I felt really sad. Every year I used to get really sad around my birthday as I’d realize another year has gone by, and I’m still dealing with this stupid eating disorder. I’m bored of you, go away. Of course, it is not that simple.

Now I’m less angry at myself when I slip up. I realize that some habits are hard to break. Sometimes life gets really stressful and unpredictable and it is hard not to fall back into ED behaviours.

But I noticed that when I would get really disappointed and frustrated at myself for screwing up, I’d fall harder and for longer. I’d feel like I failed, and that fueled more behaviours. But once I started actively trying to forget about the slip-up and return to normalcy at the next possible point (ie, the next meal), things would get better quicker. I’d be back to healthy routine in no time. Once I started accepting that I’ll continue screwing up on my way to full recovery, I became calmer and less depressed when I did slip-up, acknowledging the progress that I made, and try to move forward. Of course, this is all just my experience, my recovery.

This is getting long again, so I’ll end here.

Readers, what experiences have you found to be (maybe inadvertently) harmful in your recovery process? Can you relate to any of the points raised by Treasure et al.? Do you disagree with any of them?

(Side-note: I’m being very open and honest, so the only thing I’d ask is that you spare any advice on how to recover and what I should do. I am doing quite well at the moment; I’m happy where I am in my recovery and my life.)

References

Treasure, J., Crane, A., McKnight, R., Buchanan, E., & Wolfe, M. (2011). First do no harm: iatrogenic maintaining factors in anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 19 (4), 296-302 PMID: 21714039

I think there are a lot of very good points in here. It wasn’t until I went to a treatment center that did a much better job at normalising behaviors around food. It’s incredibly hard to develop a relatively normal relationship with food when it is something that is dispensed and forced upon you. I think, more often than not, professionals are trying to force patients in to treatment when they may not be ready. I understand that it could be for a variety if reasons one being liability and other a fear that the patient will become even more unstable. It’s a catch-22 really because you cannot force someone to get better, there has to be some willingness. In my experience I am coerced into treatment and I go to appease others but am not interested in recovery.

Eating disorders are very ego-centric by nature. I recently started seeing a specialist again for medical monitoring and one of the first things I said was that I didn’t want a lot of focus to be on my anorexia because it’s hard to not focus on numbers or symptoms when everyone else is focused on them. I think one of the most effective things is focusing on harm reduction when possible. I know that it’s not uncommon for people with a mental illness to become a revolving door patient because that is the identity and they don’t know how else to live. I cannot tell you how many people I know(including myself) who have just been in and out of treatment.

Eating disorders are incredibly frustrating for both the professional and the sufferer because they do not make any logical sense. I am both baffled and frustrated by the lack of treatment that is known to be effective. I feel like a disorder as deadly as these there should be more research not only on effective treatment but causes. I cannot believe there is not as much research on the correlation between severe EDs and trauma

Karina, thank you for your comment, I think you’ve made some really important points.

I completely agree with you that a huge part of treatment is normalizing eating behaviors. I think the vast majority need help and support in that process – it may not be residential or inpatient treatment, but certainly some kind of support: family, friends, significant others, etc.. It does sometimes feel like a catch-22 situation, for sure. I think the recent stories about the right to die in AN patients, or the right to refuse food, really highlight the problem. It is reasonable to assume that with more nutritional stabilization, these patients might desire to recover or fight the illness to some extent, yet, forcing them into recovery not always the best idea and can backfire, too. It is incredibly difficult – and every situation is slightly different about these issues, too.

Regarding the numbers, I agree with you, too. I think clinicians often don’t realize the obsession with numbers during recovery can be very counterproductive. That point is often missed, I find.

And ditto on lack of evidence-based approaches. I’m planning to cover this huge topic in more depth in future posts.

Thanks again for your comment 🙂

Tetyana

I know this was written a while ago, but I have just found your blog (amazing!) and feel compelled to comment.

I have had an ED for 13 years (I’m 24 now) and also other comorbid things…severe and recurrent depression, anxiety, yada yada. At age 13 I was admitted to a child inpatient unit, because I attempted suicide. It became clear to the clinicians there that I had previously undiagnosed anorexia nervosa, but believe it or not the ED was never treated or even discussed again after I was diagnosed, even though I remained an inpatient there for 18 months!

Throughout my teens I had relapsing and remitting anorexia/bulimia, which was known by my outpatient treatment team, and also the staff at the community youth psych place I lived at, but they never once referred me to the eating disorders service (I’m lucky enough to live in a country where healthcare is free and we have specialist services). It was only when I was 17 and had already had an ED for 6 years that I was referred to the ED service as an outpatient. However, they refused to see me because of my “high risk” of self harming behaviours. There was an appalling lack of communication between the different services I was seeing, so a huge part of my problems were completely ignored.

I FINALLY began to see the eating disorders team (specialist dietician, medical doctor, psychiatrist, psychologist and nurses) when I was 20 (!!!) and then it just all felt too late. The therapy was very good, but they suffered from a lack of resources and the inpatient unit there only has 6 beds to serve a population of 2 million. You can imagine that there were a whole lot of sick people needing beds who didn’t get them, and it was only when you were on death’s door that you were admitted. There was very good treatment for severe anorexics, who would undergo a long term admission (6 months to 1 year) and they had a very high recovery rate for that group. For me, I was underweight but not imminently dying, so I was only admitted once for a 2 week stabilisation when I had a cardiac arrythmia and neutropenia. My therapy as an outpatient continued and was brilliant because I was seen by a multidisciplinary team of experts.

However….after 6 months my depression took a very bad dive and I was admitted to the adult acute psych ward. The eating disorders service discharged me on the spot because I was now “too complex”. Once again, the ED was forgotten. In the psych ward the nurses and doctors there were incredibly dismissive, told me I wasn’t that skinny, that my ED was “mild”, and turned a blind eye to my destructive behaviours.

I mostly recovered from my ED, no thanks to professional help I might add. SO MANY TIMES I was told that I weighed too much to be treated and that I just needed to eat 6 small meals, etc. And in the ED ward I was told by a nurse that I should feel “grateful” that I wasn’t really sick like some of the girls there, which fuelled the anorexic thinking even more and made me feel completely undeserving of treatment, and like a “failed anorexic”.

Sorry for the essay, I haven’t put it all down like that before, and it suddenly makes sense that I am still struggling a lot with this demon when I have never been treated properly!

Love your blog, and thankyou.

xx

Hi bets,

Thank you for your comment! Don’t be sorry for the length–I love long comments. I’m sorry to hear you had to deal with all that crap. I am sorry, too, that so many others have to deal with it as well. It is BS, really. Complete BS. But, I’m glad you wrote what you did, because it is SO important for others to read it and to understand the crap that ED patients often face. It needs to be known and talked about.

I mean, lack of resources is one thing, because it is not the doctor’s fault, but dismissive and harmful comments (like being told you weren’t really sick, or turning a blind eye on your destructive behaviours) is appalling.

Ugh, it makes me so angry! I hope you are get good treatment soon and kick this demon in the ass.

Glad you like the blog! I like running it :).

Cheers,

Tetyana

I really like these articles because I relate to them.

About a year ago (March 30th will be a year..) I was completely out of control, to be honest. My eating disorder, at the time would be ENDOS (restricting and fasting and over-exercising with short periods of binging and purging) coupled with anxiety issues, self injury, and severe depression. I was walking home from school, planning on killing myself, when I decided instead to finally tell my mother about my eating disorder. It went well and we brought it up with our family doctor (who had been trying to figure out my dizzy spells and heart problems.. Oops). I was scared he was going to be like the health care professionals in these articles, but he was really good. He referred me to the eating disorder clinic 3 hours away.

That’s where the problem was. My first experience with them was talking to the youth therapist over the phone, which went well. I wanted to recover, and had started recovery on my own. Eventually (early June), I went into their office. I had been doing alright with my eating disorder recovery, although still cutting, still suicidal, and hating the fact that I was in recovery (still eating a less than healthy, but enough to fool even myself, amount of calories). Again, talking with the therapist went alright, she said I was doing good on my own. During the physical/medical examination, I didn’t have any immediate problems, and my weight was healthy. They said to me that I was doing good, might want to go see a counselor, and haven’t spoken to me since. They didn’t diagnose me with anything, and while they weren’t rude, they made me feel very illegitimate.

I’ve since relapsed completely into bulimia, am seeing a counselor (two for a while), but struggling a lot without any treatment available to me.

As far as depression goes, I’m not diagnosed with that either, despite ending up in the hospital overdosing (suicide attempt).

I think it’s because of these things that I minimize my problem a lot.

Thank you for this article and I apologize for such a lengthy comment.

Kayla,

Thank you for the comment. What you wrote is really important and I’m really sorry you’ve had to experience that and feel illegitimated. (Also, never apologize for the length of the comment! It is not lengthy and it is important. It is fine to take up pixels, seriously.)

Do you know why they didn’t diagnose you with anything? Is it possible to get diagnosed and will that help you with getting access to treatment?

Bulimia and depression are incredibly serious issues. I would urge you to try to get diagnosed if possible and try to emphasize–not minimize–your problems. I know we all tend to think we’ll be okay (except when shit gets really bad) and things are not “that bad” — but they are bad, and we all need help sometimes (and sometimes for very long periods of time.)

Please let me know what happens and if you are able to get more treatment. I’m worried.

Tetyana