Treating anorexia nervosa is hard. Treating chronic and severe anorexia nervosa is a lot harder. Although the situation seems to be improving, there are really no evidence-based treatments for anorexia nervosa – particularly for those who have been sick for a long time.

Patients with severe and enduring anorexia nervosa have one of the most challenging disorders in mental health care (Strober, 2010).They have the highest mortality rate of any mental illness with markedly reduced life expectancy (Harbottle et al., 2008). At 20 years the mortality rate is 20%, and given the young age of onset this results in many young adults dying in their 30s, and a further 5–10% every decade thereafter (Steinhausen, 2002)… Patients are often under- or unemployed, on sickness benefits, suffer multiple medical complications… have repeated admissions to general and specialist medical facilities, and are frequent users of primary care services (Birmingham and Treasure, 2010; Robinson, 2009).. pose a significant burden to parents and carers (Treasure et al., 2001).

The treatments that many often claim are evidence-based are often only applicable to a select subgroup of ED patients, and even then, the evidence is usually weak. (I’m referring to Maudsley/FBT (family-based therapy) for adolescents with <3 yrs duration of AN and CBT for bulimia nervosa.) But what about those with long-standing anorexia nervosa? In a recent review, Phillipa Hay and colleagues set out to conduct a systematic review of randomized controlled trials of treatment for chronic AN.

Randomized controlled trials or RCTs are at the heart of evidence-based medicine:

The randomized controlled trial is one of the simplest but most powerful tools of research…[it is] a study in which people are allocated at random to receive one of several clinical interventions… the methodology of the randomized controlled trial has been increasingly accepted and the number of randomized controlled trials reported has grown exponentially… and they have become the underlying basis for what is currently called “evidence-based medicine”.

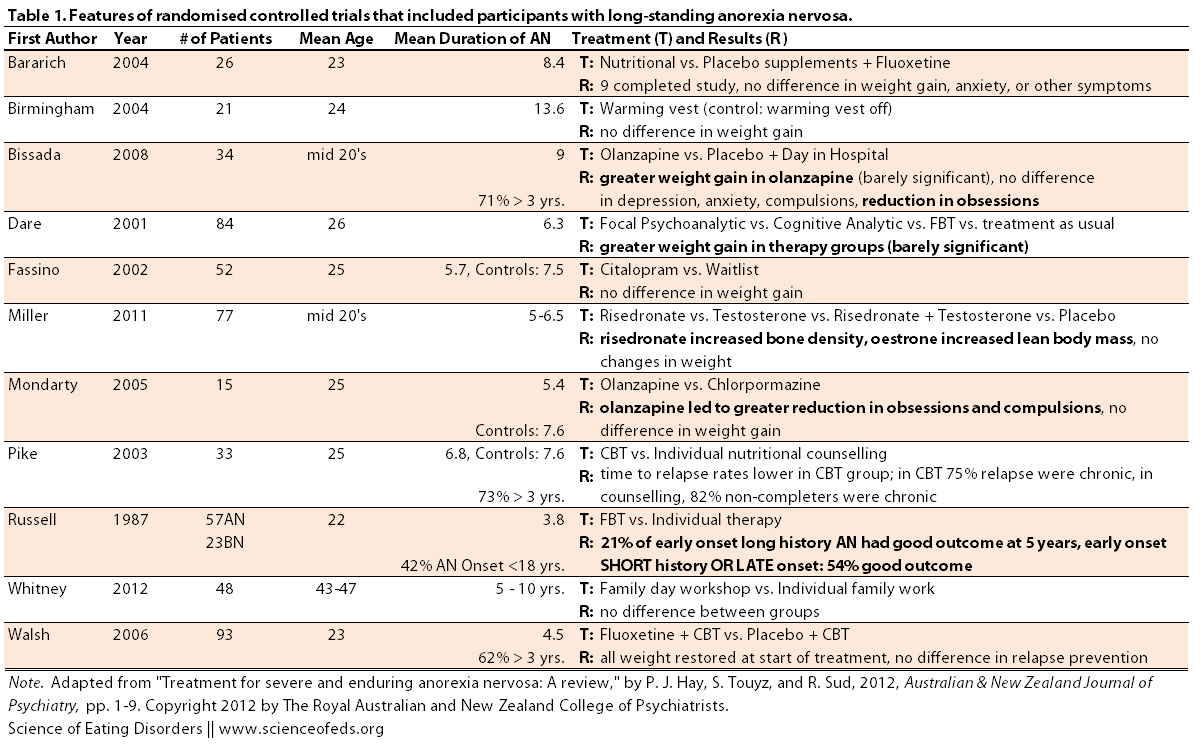

Hay et al searched the literature to identify RCTs where, among other criteria, the mean duration of illness was at least three years. They found eleven studies, but they could only confirm that a majority had a mean duration of over 3 years in just four of those studies.

I’ve summarized the studies in Table 1 (click to enlarge), highlighting the differences that were found between the treatment and control groups. (Side note, those that I labelled barely significant had p values of around 0.3):

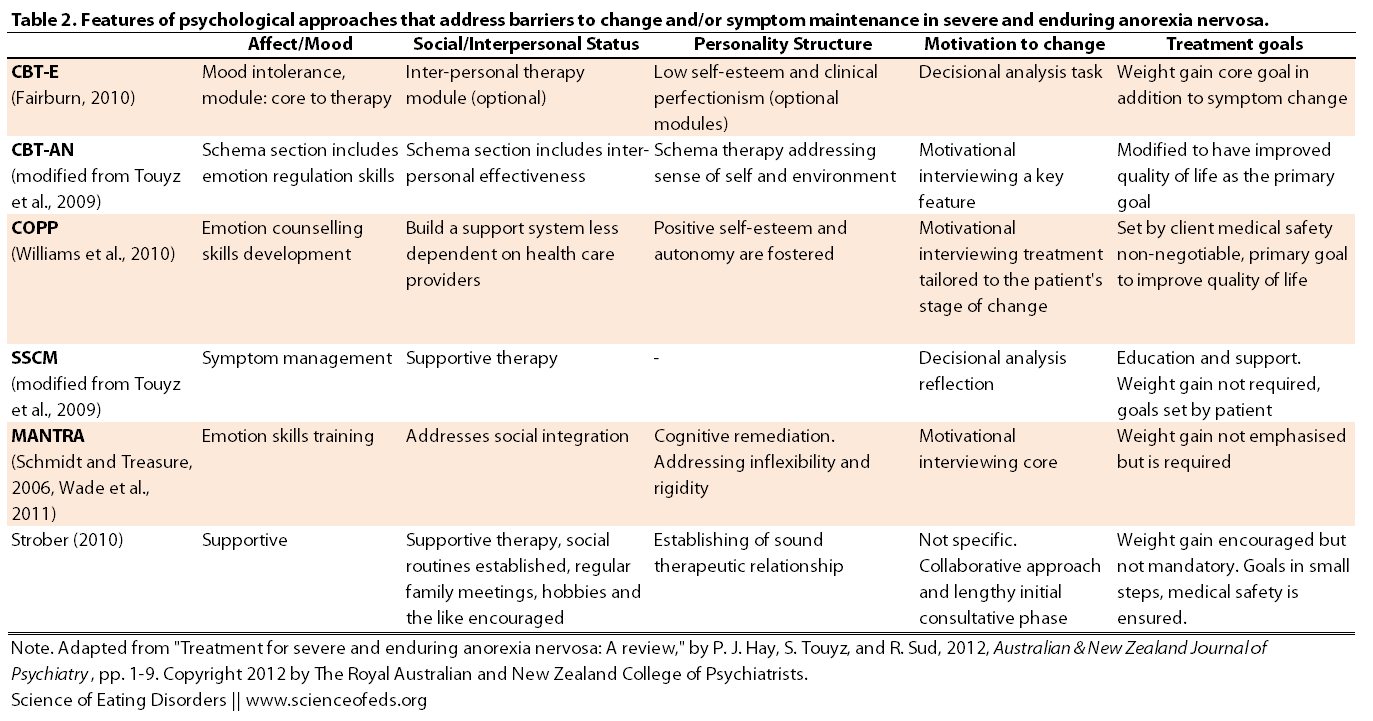

In addition to the aforementioned RCTs, Hay et al identified several case series and studies (which were not RCTs) that have specifically tried to address the perpetuating factors that lead to long-standing anorexia nervosa. The table below summarizes these novel treatment approaches.

One novel approach (Fairburn, 2010) uses a variant of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), developed specifically for chronic anorexia, called CBT-E (E for extended). In addition to the regular CBT modules, CBT-E includes additional modules that focus on factors that maintain and perpetuate AN, as well as dealing with mood intolerance, interpersonal relationships, perfectionism and self-esteem. In a study utilizing this approach conducted by Byrne et al. (2011), out of the 34 patients with AN (2 males, 32 females) with a mean duration of illness slightly over 10 years, 12 completed the study, 3 attained partial remission and 3 attained full remission. Full remission was defined as having a BMI of 18.5 and above, Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) scores less than 2.46 (which is within 1 standard deviation from the community norm), as well as the cessation of restricting and/or binge/purging behaviours.

That sounds pretty okay so far (remember the average duration of the illness is over 10 years). But here’s the kicker, I went to check the original paper: the “full remission” is based on the absence of symptoms for… drum-roll… 28 days. Err what?

The other trials showed similar trends; there’s some improvement but often the weight gain is not sufficient to be in the normal weight range and the symptoms of rigidity and perfectionism are still present. That’s not to say that these approaches are useless. They are not: any improvement is better than no improvement – especially for someone with a long history of AN.

If you take a look at Table 2, you’ll see that a lot of the approaches are centered around CBT in combination with motivational interviewing. The idea, at least in part, is to address the thinking styles common in AN that tend to perpetuate the disorder. Also note that while weight gain is a goal in many treatment approaches, it is not mandatory and/or emphasized as the primary goal.

Now, I am predicting that a lot of Maudlsey/FBT proponents will comment about the importance of weight restoration and how psychological and cognitive changes cannot happen until normal weight is restored (or at least wont be as effective). That might be true for some BUT it is definitely not true for all. To say that it is, is to deny the very real experiences of many ED sufferers.

But, there are a few even more salient points I want to make:

- we are talking about long-lasting, chronic anorexia nervosa: at least 3+ years, but in many cases it is 6, 8 and 10, even 15+ years.

- most of these patients are adults, in their mid to late 20’s, and some are older (average age in one study in Table 1 was ~45)

- these patients likely failed (were kicked-out or dropped-out) from previous treatments, probably in inpatient care or residential treatment centers, or they relapsed soon after discharge, in other words: other treatments didn’t work for them, the treatments failed them as much as they failed the treatment.

I’m going to harp on this a little more because it is an important but often ignored issue. You wouldn’t treat stage I cancer the same way you’d treat advanced stage IV cancer, right? Nor do you treat mild cases of depression the same you’d treat long-lasting chronic depression, right? To keep trying to same approach, or slight variants of the same approach for all patients, regardless of age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnic background, family relations, socioeconomic status, duration of illness, comorbid psychiatric disorders, and so on, is.. well, stubborn to say the least. Almost dogmatic.

And don’t get me wrong: I do not think long-lasting anorexia (or bulimia) is untreatable, nor do I that high heritability means genetic determinism (it doesn’t). Eating disorders, not unlike cancer, are heterogeneous. To quote myself from my very first blog post:

… when comes to anorexia, genetics and the environment both play important roles. Furthermore, the precise influence of genes to environment will vary from person to person. For some patients, genetics may be the main factor, while for others, the environment might play a more important role in leading to anorexia. Naturally, this complicates the picture, in terms of research but also in terms of treatment. Perhaps – and this is just my hypothesis – this may explain why patients respond differently to various treatments. Perhaps a large part of it is due to differences in the degree to which genetic and environmental factors played a role in the development and maintenance of the patients eating disorder. Perhaps if we were able to determine the extent of, say, genetic influence in any given patient, we would be able to tailor treatment for that person…

But anyway, the other reason I’m bringing all of this up is because I want to point out a study that essentially used a harm reduction approach. Williams et al. (2010) (see Table 2) utilized a treatment approach meant “to improve quality of life and minimize harm.” The goals and the pace of therapy are “set by the client and the focus is on symptom management, skill development and understanding benefits and risks of symptoms.” Moreover, this approach doesn’t require inpatient or residential stays (which are problematic in their own ways): it is set in the patient’s own community. Medical safety, however, is a “non-negotiable” goal.

In 18 patients with a mean duration of AN for 15.2 years, this approach, called COPP (Community Outreach Partnership Program), led to significant improvements in some areas (but not all) outcomes that were evaluated after 25 month of treatment.

Note the link above (or here) leads to the full Williams et al paper, I shared it through my Dropbox folder because I think it is an important read. I strongly suggest everyone checks it out (although the excerpts about patients with EDs can be somewhat triggering or upsetting). We cannot forget about the patients that drop-out of treatment, relapse or stay chronically sick in and out of hospitals. And we cannot keep using the same treatment approaches and hoping that they will magically work, even though they’ve failed before.

In this ‘new kind of paradigm’ for chronic illness there is an emphasis on early treatment alliance and not hastening into a specific intervention, weight gain is not the principal objective, re-feeding is negotiated carefully and collaboratively. Nutritional improvement, however, is encouraged, routines of social activity are established, hobbies and pursuits encouraged, regular medical examinations done, and regular meetings are undertaken with family members and supportive others. [Strober (2010)] emphasises the professional challenge of working with these patients, the ability to ‘not require successes measured by patient progress…to face frailty and profound sickness with ease’ and therapists avoiding the ‘risks of treading too heavily on their (the patient’s) efforts at salvaging “marginal comforts.”

The authors stress the need for more randomized controlled trials in evaluating the effectiveness and efficacy of treatments, but at the same time noting the importance of open trials in exploring new treatment approaches.

I think when looking at treatment approaches and determining what works and what doesn’t, we cannot put all anorexic patients into one group, or simply divide them based on the presence or absence of bingeing and purging behaviour. I think the effectiveness of therapies that might work incredibly well for a subpopulation of patients gets diluted in a large trial by subpopulations for whom the treatment is ineffective (or harmful). I think clinicians and health professionals who work with ED patients need to listen to them as well as their families/caregivers/partners. Alliance with the patients and, when applicable, the patients family, is crucial for treatment to be successful.

It is hard. There’s no question about that. But treatment that may work for a self-aware, highly educated single female in her late 20’s or early 30’s, who is estranged from her family, will be different than treatment that may work for an adolescent female who is in denial of her illness and lives with her stable middle-class family. Replace “female” with “male” or “trans female” or “trans male”, or add some psychiatric comorbidities, and without question the best approaches to treatment change, too.

References

Hay, P.J., Touyz, S., & Sud, R. (2012). Treatment for severe and enduring anorexia nervosa: A review. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry PMID: 22696548

I agree with you on many many levels. Every patient is different and their treatment should be tailored to THEM, not to what works for the majority.

A couple of random (non evidence based) theories. One is neuroplasticity – building new pathways in the brain so that the “default to eating disorder behaviours” pathway is weakened?

The other is that by narrowing the diagnostic criteria to the DSM is particularly unhelpful. We are narrowing the treatment options by recommending (and continuing with) treatment that works for the majority, rather than working out it is not working and trying something else.

I am not sure that all “anorexia nervosa” patients are suffering from the same illness. There are many similarities (aversion to food being one!) but there are also unique features that need to be tackled and treated.

Sigh.

Charlotte, thanks for your comment!

I think neuroplasticity or the idea of strengthening some pathways while weakening others is essentially what happens during recovery, regardless of how you approach it. CBT, for example, is just another name, in my view, for that. Thinking differently, behaving differently and dealing with emotions in a different way can all be connected to neurobiological changes. It is not even necessary “building new pathways”, as much as strengthening and weakining different connections. But, I don’t think neuroscience is anywhere close to figuring these things out such a fine level, but the concepts are nonetheless useful.

The DSM is crap, I completely agree. There are plenty of non-fat phobic patients, those with BMIs in the higher ranges because they are either not that sick yet, have high starting BMI, or are in partial remission, amenorrhea is one that’s often ignored by researchers and is getting removed anyway, but yeah… there’s very little in the DSM on eating disorders that I think has scientific validity. But maybe I’m hyper-critical. I don’t think clinicians really use it or rely on it (at least not good ones), it is made by scientists, mostly, and scientists like to classify, organize, demarcate things.. it makes research oh-so-much easier, but may have little connection to the real world.

The idea of that not all patients with AN have the same illness is a good point. I think that there is some commonality among all patients who have an inability to maintain a normal weight and a desire or compulsion to restrict their intake (for whatever reason). they might have different causal factors, but, it is almost crazy how starvation seems to lead to remarkably homogeneous characteristics in most people. I do think that the etiology is important, though. Like I mentioned in my previous post, for example, trans women or men have a whole different set of issues to deal with, and even though their EDs might look the same, from the outside, resolving their EDs might mean going through with gender reassignment surgery and hormone therapy, as opposed to “loving their body”.

Yes, you’re right, I’m stuck on the weight restoration part. It’s like discussing whether or not to pull drowning people out of the water and considering one inch below the surface as better than one foot below.

Without full restoration and behavioral normalization for 6-12 months we’re comparing one inch with one foot and — predictably — not seeing a difference.

I consider it iatrogenic and a massive public fail that we don’t do this, and deeply disappointing. I don’t think this should be different for young patients new to the disorder than so-called “chronic” patients. Your analogy to later stage cancer is apt because we don’t wait to treat early cancer while we wait for it to advance and we understand that the failure to treat effectively early is what causes later stage disease.

We wouldn’t have a set of protocols for diabetes like this — where we don’t consider blood sugar normalization a bottom line. We oughtn’t for nutrition and behaviors, either. Another generation of ED patients is at risk here and we are losing the chance to save them.

Laura, thanks for your comment! (I totally did put that in there for you ;-)).

I just wanted to say one thing. Your analogy of a drowning person and how there’s no difference between one inch below the surface compared to one foot below is missing one key element: quality of life.

To that drowning person, their quality of life is the same at one inch below the surface as it is one foot below. But, to someone with an eating disorder, gaining from a severely underweight BMI, to just slightly underweight, can mean the difference between life and death, resumption of menses, the ability to have a social life, to resume/begin school/work again, and all sorts of things. To someone with bulimia, reducing binge/purge episodes from a few times a day, to once or twice a week, can mean the difference between being able to work and go to school, to being essentially paralyzed by the disorder. Is it “ideal”? No. But, aiming too high too fast can, and often does, lead to relapses and failures.

who may not be able to tolerate, at least initially or ever, a normal weight, still deserves and benefits from treatment, often times substantially. Often times, full weight restoration might just set them up for relapse. I’m not talking about everyone here. I do think weight restoration is important, I do.

But to view it as this black and white thing – above or below the water – is to miss everything that is gained by reducing symptom frequency, symptom intensity, and the disordered through processes. In other words, quality of life measures.

I just can’t agree with you. Quality of life would be a better measure if the lack of weight normalization and behavioral normalization were not a major part of why the patient thinks and acts in this way.

When we as parents, clinicians, and advocates set the bar lower than OUT of the water we do so for our own comfort – not in the patient’s best interests.

Letting the cancer grow, staying with the analogy, because the chemo is harrowing is a failure on our part and not one the patient can be expected to guide.

“Too fast” is a medical decision. Once we’ve allowed a patient to be ill for a while we need to set a pace that is medically safe. But every hour, every month, every year we collude on sub-optimal nourishment and partial remission of behaviors is — if we understand it — keeping the patient ill.

We have to change thinking, laws, and protocols to make this the standard but that is OUR problem to solve and not a reason to let ED write ED policy.

I’m not entirely comfortable with using analogies to cancer, etc. but if we’re going to make that comparison, let’s at least make it an accurate one. Not all people with cancer elect chemotherapy and radiation as their treatment of choice. Or invasive surgery. Doctors rarely mandate a course of treatment. While a strong medical recommendation may be made, ultimately the final decision rests with the (adult) individual – and some decide that they would rather not undergo the arduous side effects, illness, pain and nausea from invasive treatments, even if it means a better survival rate. And so on. The presence of ego-syntonic features ≠ psychosis, and neither ego-syntonic features nor psychosis are a free pass for medical paternalism.

The focus on refeeding and weight restoration is vitally important and often underrated, I agree. But when presented as the sole option, presents a significant barrier to engaging in treatment (remember, we’re not all adolescents living in a supportive home environment with access to resources for FBT), and that’s not the population this article is targeted towards. For many independent adults, “life” doesn’t “stop until we eat” but rather, life must carry on regardless. Programs like United Couples Against Anorexia (U CAN) are an excellent idea but the problem is, often the people with chronic/severe and enduring eating disorders are isolated and lacking in those kind of close friendships or familial or romantic relationships than can form the basis of supportive treatment.

The standard treatment modalities we have now aren’t working, and I’m in agreement with you that there is too much focus on “fluff”, but I wonder how we can change the conversation about weight restoration and refeeding to include what happens AFTERWARDS, as well – otherwise the focus is merely a throwback to earlier ineffective models. A family member of mine was treated for anorexia as a teen in the early 1970’s with alternating doses of food and Valium, nothing else, and released after her weight reached a target #. She continued to struggle with periods of full relapse and subclinical symptoms for the next 20 years. I have acquaintances now who’ve been weight restored appropriately, have had their eating normalized by months in varying levels of treatment – and as a result, have no self-efficacy nor any intrinsic motivation to maintain their progress. I used to lurk on the ATDT forums for years – having someone make me eat and sit with me after, non-negotiable, was a fantasy. I would have loved to have that responsibility taken from me. But in later years, it’s become apparent than if I wait for someone to step in and take that responsibility from me, I’ll be waiting forever – it’s no one’s responsibility but mine. No one is going to make me eat and keep me from purging, so I’d better figure out how to step up to the plate (pun intended) because I have things I want to do with my life that are incompatible with having an eating disorder.

We should not let “ED” write ED policy but neither should we allow traumatized caregivers to do so, either. In both cases, judgement is clouded to some degree (and both groups, I think, are prone to black-and-white thinking.) And I think there’s much to be gained from looking at a patient-driven approach for this segment of the population (chronic/severe-enduring) and asking questions like What do YOU want out of treatment? What is important to you? What keeps you from pursuing treatment? What are YOUR goals?

Harm-reduction doesn’t necessarily mean accepting stasis, in fact progress is a crucial component of the model as proposed in Tatarsky’s model of integrative harm reduction psychotherapy (IHRP) – but it’s patient-driven and -defined. (N.B. There’s actually an interesting offshoot of HR called Gradualism, where the eventual goal is elimination of maladaptive behaviors or symptoms.)

“Harm-reduction doesn’t necessarily mean accepting stasis, in fact progress is a crucial component of the model as proposed in Tatarsky’s model of integrative harm reduction psychotherapy (IHRP) – but it’s patient-driven and -defined. (N.B. There’s actually an interesting offshoot of HR called Gradualism, where the eventual goal is elimination of maladaptive behaviors or symptoms.)”

Saren made a GREAT point here, Laura — and it is something that is often missed when people begin to throw around terms like “harm reduction”. Harm reduction DOES NOT mean giving up, and it IS NOT palliative care under a more politically correct name. You are correct that weight restoration is extremely important, but I think we need to acknowledge that with adult sufferers who have SEED (severe and enduring eating disorders), traditional treatments have likely been tried and have failed. . . In addition, these patients are unlikely to SEEK voluntary treatment because they are either afraid of the “non-negotiables” of treatment (i.e. rapid weight restoration, etc.) or they are skeptical that another round of similar treatment will help.

HR, when applied properly, allows for clinicians and the sufferer to meet one another “half-way,” so to speak. A patient is much more likely to continue to see their treatment team if they are setting goals are achievable and realistic. As Tetyana pointed out, with regard to QUALITY OF LIFE, there is a huge difference between a severely ill non-functional individual (i.e. low caloric intake, passing out from exhaustion, frequent purging leading to medical complication) vs. someone who is still at a low weight, but working to eliminate or reduce the purging, up their caloric intake to a stable level to maintain weight, etc.

I think your fear that HR can be used as a cover for clinician “laziness” is well-founded (i.e. HR protocols in the UK are ridiculous and frankly dangerous). HR should only take place when the clinician/sufferer have agreed it would be the best course of action, NOT as a cost-saving strategy in which chronically ill but treatment ambivalent or treatment motivated patients are assigned to HR based upon their past failures in traditional treatment.

In addition, I liked Saren’s point about Gradualism. HR is what it means — reduction of harm that is caused by the ED. Therefore, stasis and complacency on the part of the professional or sufferer should never be a part of this protocol. When the hypothetical ED patient has eliminated purging and upped calories to a sufficient levels to maintain weight, perhaps it is then time to discuss slow weight gain, adding variety to the diet, reducing exercise by 10minutes per day, eating 1 meal/week in public or with a family member, etc. . .

The key principle is that it enables the clinician to meet the sufferer at their level with the ultimate goal of facilitating recovery (either full or partial).

Laura — you run a forum, a blog and an organization that is dedicated to FBT — Given Tetyana’s analysis of this peer-reviewed literature, I don’t see how you can refute that this is an option that at least requires exploration. . . Maudsley was a paradigm shift that turned conventional therapy in the ED world on its head — is it so hard to believe that HR or Gradualism might be similar?

In addition — I think the most obvious issue to point out, is what IS a chronic ED or a SEED? What does it look like for AN, for BN, for ED-NOS. . . What is recovery? What is remission? What is partial remission?

We need scientifically validated definitions for all of these terms before we can really begin to compare treatments. . .

I’ve noticed how the DSM defines the severity of anorexia nervosa by lowness of BMI, but that doesn’t make sense, because there are some people with BMIs of 17 who eat more than people with BMIs of 23 and a low weight doesn’t necessarily mean you’re more entrenched or distressed.

Yeah, the DSM is crap.

I think it would be a good article idea to write about ED treatment in the UK, because recovery sites are generally US based (and the UK does have issues with how it treats ED’s).

Hmm, good idea. I know NOTHING about treatment in the UK and how it differs from US or Canada (or other English speaking countries). Do you have any particular links/papers that talk about treatment in the UK (or anyone else for that matter)?

http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR162.pdf

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/erv.2400010104/abstract

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/erv.492/abstract

idk if all those links are relevant, i just searched ‘anorexia treatment uk’

http://bjp.rcpsych.org/content/175/2/147.short

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01726.x/abstract?deniedAccessCustomisedMessage=&userIsAuthenticated=false

(Trigger warning for weights in the articles)

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2074086/Kate-Chilver-dies-16-year-anorexia-battle-worst-case-doctors-seen.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2094031/Dr-Melanie-Spooner-inquest-Childrens-doctor-tortured-anorexia-died-3st-11lb.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2131420/Head-girl-17-died-anorexia-trying-hide-year-battle-illness-parents.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1127710/Gifted-Cambridge-bound-student-dead-year-battle-anorexia.htmlhttp://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-1320292/Anorexia-killed-Anna-Wood-16-1-year-starting-diet-mother.html

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2137423/Bethaney-Wallace-Anorexic-cover-girl-model-19-dies-sleep-weight-drops-6-stone.html

I think those articles (of which there are many more I didn’t link) are evidence that treatment here isn’t good enough really.

IMO patients with anorexia who are very sick should be sectioned- it’s not forced recovery but I don’t believe in letting sufferers choose to starve to death. :/

I wish I could “like” this entire comment. 😛 I could not agree more… for so many adults with chronic EDs it’s simply NOT POSSIBLE to obtain the type and duration of treatment required to obtain “full weight restoration” nor is it often possible to have the 24 hour intensive support needed to ensure this happens. Of course it would be awesome if everyone could get this kind of help, but they can’t. The “full nutrition/full weight restoration or you’re giving up on the patient” argument makes no sense. Helping someone maintain a healthier but still underweight BMI, focusing on manageable symptom reduction, in severe cases even just “not dying”… how is that giving up on the patient? In the real world, you have to work with what you have. Isn’t it better for someone to live a LIFE with some lingering ED symptoms than to DIE “giving up” because they think it’s all or nothing, full recovery or throw in the towel?

Becca, thanks for your comment! I was playing around with various comment rating plugins and didn’t like them or screwed up other things because they weren’t compatible with the current wordpress version! Is it something you’d like to see? To be honest, I don’t know if I want to “rate/like” comments so much, because I kind of think everyone’s opinion is important and I don’t want to “gang up” on people just based on who happens to be in the majority of readers for a particular post, you know what I mean?

And I agree, Saren articulated her points really really well. I also completely agree with you.

I’m not talking about harm reduction in a sense of letting someone stay at a really low BMI. To me, HR means always trying to improve and aiming, at the pace suitable for the patient, for full recovery. Like you said, life is not an ideal situation, and it is certainly better to have an almost normal but still slightly underweight BMI, than be really sick and not medically stable. No, it is not “ideal”, but little in life is ideal. It is certainly not giving up, it is being realistic given the financial and social situations of that patient; not everyone has supportive parents or caregivers, unfortunately.

“I’m not talking about harm reduction in a sense of letting someone stay at a really low BMI. To me, HR means always trying to improve and aiming, at the pace suitable for the patient, for full recovery. ”

This, I think is the entire post and discussion compressed into two sentences. I really don’t understand how anyone could disagree with this philosphy given what we know about treatment-resistant AN.

What about people who just have not been able to tolerate weight restoration? Half of deaths caused by anorexia are related to suicide. I think someone has a better qualify of life receiving support measures without unrealistic expectations that life will resume to normalcy with weigh restoration. NOT EVERYONE WILL FULLY RECOVER. Maybe everyone can, but they do not. What you suggest may be of benefit to the majority, but what about the minority who go on suffering, labeled as “treatment resistant” and so forth? What a disservice to us!!!

Tetyana, thank you for writing this article and including the references and links.

I, as a parent of a person whose ED is severely entrenched and who is almost 40, I was encouraged to see your emphasis on the medical piece being non-negotiable.

I also am now on the fence about full weight restoration not only because my recovery from bulimia involved ten years of weight restoration following my decision to quit but also because I think I would look for more rational decision-making and engagement as well as the ability to set-shift (Tchanturia) in order to begin the treatment you describe. I think the ability to think “rationally” comes before the body’s set point.

I have shared your piece with this person’s team.

Thank you, again.

Jennifer, thank you for your comment.

I do think medical stabilization is important. It is true, one cannot think clearly when they are severely underweight or, often, if they are stuck in the bulimic cycle.

I think you are absolutely right when you say that you “think the ability to think “rationally” comes before the body’s set point.” Indeed, I think so too. In fact, I KNOW it is true for me.

Thank you so much for this, Tetyana. In more recent years I’ve become less and less hopeful about better outcomes for those of us with severe chronic ed. Part of this is the rise of treatments targeted at younger people with families or partners/carers who are able to commit to helping their loved one 24/7.

I know nobody has actually said this, but I’ve felt a strong sense of “If you are older and have chronic ED, you are a lost cause, and we are wasting our time trying to help you.” I’m ALL for early intervention, and for expending every possible resource in trying to turn around the course of the ED as early as possible in the person’s life, and for that reason, I strongly agree that weight restoration is absolutely necessary in these cases because yes it’s absolutely true, proper therapy cannot happen without it, the personal perspective on weight, themselves, the world, etc can’t become more rational, issues like depression will not improve etc. Also preventing as much physical consequence as possible is essential.

But when you are chronically ill, weight restoration seems to become the only thing they have left to offer you – and from experience – many many many experiences – I have been through refeeding/weight restoration well over 100 times in my lifetime – it often doesn’t work for us. And doing it over, and over and over, putting us through that distress and our bodies through even more of an extreme up and down yoyo pattern than if we’d be left as we were, makes us psychologically and physically MUCH sicker than if we’d been left alone too. At some point, there needs to be an opportunity to concentrate on quality of life and stability rather than the all or nothing gain weight or go away and suffer alone approach (for those who aren’t on involuntary orders).

For this, there needs to be so much support. There need to be therapists who are willing to take the challenge to meet these people where they are at and work with them in whatever capacity they are capable of – it may be greatly reduced, but those with chronic eds often do develop an ability to function despite very low weights if they are more stable, in a reduced capacity, but enough nonetheless to engage in even a small amount of therapy that might help them at least find more peace within themselves and with their issues. There needs to be support for them living in the community with greatly weakened and fragile physiques, (like home and community care and recognition as ED as causing mobility problems so they can access support for that) and access to respite care when needed.

All of this might sound pretty hopeless BUT – it isn’t giving up. In my own case, I was put through almost 15 years of HELL because the only options those treating me had were weight gain or let me die, and legally they cannot let me die.It was like reliving that hell, over and over and over, and I would have rather died for most of it, it was psychological and physical torture far greater than the ED itself.

Anyway, after all these years something has finally clicked just enough for me to manage to stabilise myself, but I still have questions – would I have gotten this physically or psychologically unwell if I’d been allowed to stabilise much earlier rather than forced repeatedly to gain very large amounts of weight very fast, causing even greater distress and physical stress? Much of this time, I would stabilise at a low weight, and probably would have stayed there long term but when I was forced to gain weight, every single time I lost it again pretty much immediately I lost MORE, leading to an ever downward spiral.

A huge question is, how to identify when someone would be better served with this approach? I would hate for anyone to miss out on what might have been ‘the’ refeeding event when something finally ‘clicked’ for them and they took off from there and kept going. But in my experience, if it hasn’t happened after several tries and the person is just getting sicker, then most likely further attempts at the same thing isn’t going to help them, only exacerbate things… just please don’t then give up on us altogether and leave us out in the cold. Thank you – I hope this makes sense!

Yes, Fiona, it does make a lot of sense and yes, one of the BIG questions is who should be offered these approaches (which perhaps would be better named something like “Patient Centred” rather than “Harm Reduction”?, I don’t know), along with all A:)’s questions of what IS a chronic ED or a SEED? What does it look like for AN, for BN, for ED-NOS. . . What is recovery? What is remission? What is partial remission? Also who should continue to be offered the existing evidence based treatments like FBT, CBT, time and time again and not be brushed off as a failure, “treatment resistant” or “non-compliant”.

I do think though that ALL cases probably need a lot more time and care after weight restoration than they are habitually given by treatment providers, certainly in residential and hospital settings and probably even at home via FBT in many cases. That is not in the least to infantalise the suffer and keep them in the sick role for longer than necessary, but just to acknowledge that these are hugely difficult illnesses deserving of care and attention from professionals and the community in the long term. Going back the question of care in the UK, one service I know of is having trouble with demand and long waiting lists – a suggestion seriously made by the financial management was to offer people only 10 weeks of CBT-E instead of 20 and then they’d be able to treat twice as many people! Talk about selling patient, clinicians and the science short.

I want to stand up and give these people a round of applause. Treatment like this has been a long time coming.

Indeed – I agree.

That is my daughters email address! She will be 22 and has been battling anorexia since age 12!

Hi Julie, who is your comment directed to? I’m a little bit confused.

Having been in treatment as both an inpatient and an outpatient, I have to say that the greatest challenge is usually encountered in the afterwards. Treatment directed at where you are (in my case, a teenager the first time) doesn’t prepare the patient for what comes next, nor does it equip the family enough to be supportive without enabling, ignoring, or intruding. As an adult patient (with two children, a mortgage, a spouse, a job, a home) it’s not as easy to just put life on hold to “get better” – and again, what happens afterwards? In all my years of treatment, the most disappointing and frustrating part has been wanting to understand and being told “it’ll all work out when your weight is restored”. There seems to be a lack of willingness, at least in canada, to use the technology available and get the kind of data that would help patients, clinicians, researchers alike. As I prepare to enter my second decade with anorexia/bulimia/anxiety/exercise addiction, I wonder what will be in store for me physically, and yet I can’t find a doctor willing to do a CAT scan, bone density test, EKG, etc because “the results won’t matter when your weight is restored”. I get it, a healthy weight is important, but doesn’t it make more sense to let me work my way up to it, understanding the science behind each step, feeling confident that I’m actually making changes for the better, for the future?

Rachel, I could not agree more. The part you mention near the end of your comment relates to what Andrea wrote on her latest blog post: “it makes a lot of sense, in my opinion, to honour the voices of the individuals with lived experience when defining recovery and trying to assist in its achievement. If those individuals disagree with the definition you are putting forward, the goals you are setting in getting there, and the ultimate outcome, what is the point?”

I’ve also seen well-meaning but incredibly annoying “inspiration” quotes about how *everything will work out* (e.g., bills will be paid) if one prioritized ED recovery. Unfortunately, that’s not always (or often) the case. Ignoring the reality that adults living with enduring eating disorders face won’t get us anywhere, I feel.

Thanks so much for your comment and I really hope that you will be able to find a doctor who will be willing to work with you and actually listen to your goals and desires. :/