Hi all, Gina here, again. This article is short and sweet, as is my post. I’m becoming increasingly interested in some of the more cognitive aspects of eating disorders and seeing as my background on the subject is pretty limited (re: none, although I’m taking a cognitive science class this term), I was hoping to generate some discussion /or references from readers that I could incorporate into further posts. Cheers!

It has long been suggested that people with eating disorders (in this case, specifically anorexia nervosa) display some core deficits in cognitive ability — namely impairments in executive function (Fassino et al., 2002; Pendleton Jones et al., 1991; Tchanturia et al., 2001, 2002, 2004).

If you’re like me and don’t study cognitive science, executive function basically means that people with AN show abnormal mental rigidity, working memory, capacity to manage impulsive responses (response disinhibition) and abstraction skills (i.e. abstract thinking, complex problem solving).

Although the existence of these effects has been studied, at the time of this publication, little had been shown to explain the observed abnormalities. A 2007 study by Tokley and Kemps (available here) explored whether or not a preoccupation with detail could account for impaired executive function in patients with AN.

Specifically, Tokley and Kemps examined the role of field dependence-independence and obsessionality, as indicators of a preoccupation with detail, determining whether these variables could account for poor abstraction in patients with AN. They further studied the roles of perfectionism and mental rigidity (sub-components of obsessionality), as well as anxiety, depression and BMI, in cognitive deficits.

Field dependence-independence refers to a concept in cognitive science in which field independent people tend to focus on parts of things while field dependent people tend to take a more global view of the whole picture. Anorexics have tended to be more field independent, although there is not a universally accepted relationship between the two (Tchanturia et al., 2004).

Tokley and Kemps sampled 24 women age 16-31 with a current diagnosis of AN (being treated at the Flinders Medical Centre Weight Disorder Unit) and 24 healthy controls who were matched to the AN patients based on age, education and socio-economic status. It is worth noting that control patients were eligible for the study if they hadn’t displayed any ED behaviors (as determined by diagnostic questions on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire) for just 4 weeks. In my experience (and I imagine I’m not alone), being behavior free for a month does not necessarily mean that the person doesn’t have an eating disorder (although a month behavior free is great). The authors cite the lack of efficient screening of controls as a limitation of the study, as well.

Mental rigidity, field dependence, obsessionality, abstract thinking, perfectionism and depression/anxiety were all tested by self-reported questionnaires and cognitive assessments. The experimenters also assessed participants verbal IQ, processing speed crystallized intelligence (i.e. specific, acquired knowledge. Which differs from what is known as “fluid intelligence”, or ability to learn/reason) to ensure that results were not due to a general intellectual deficit. The paper goes on to explain exactly what tasks comprised each assessment which seemed a little verbose when I tried to summarize it. Refer to the text for the specific cognitive science behind testing each measure.

Results first indicated that patients with AN have reduced abstract thinking skills.

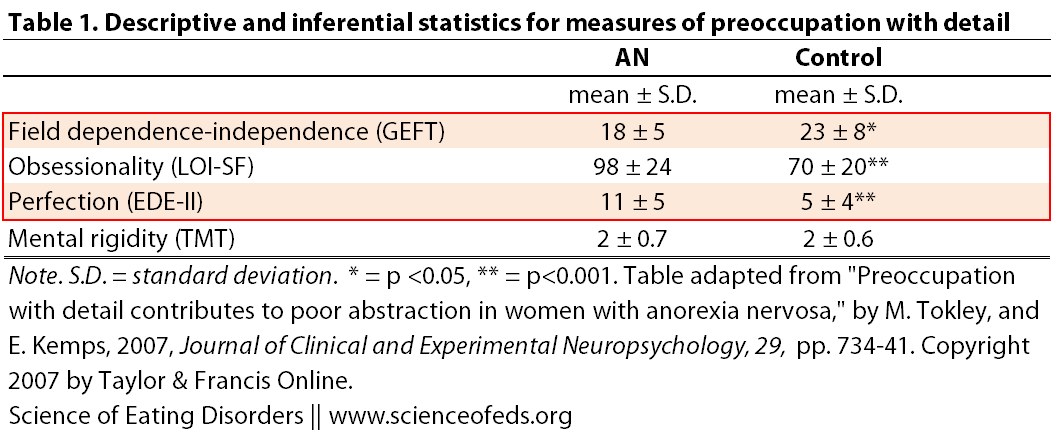

The table below shows statistical measurements made from assessing preoccupation with detail (click to enlarge).

AN patients displayed a more field-independent cognitive style than the controls…AN patients also reported significantly higher levels of obsessionality and its sub-component perfectionism. However, there was no group difference in mental rigidity…contrary to expectations, AN patients did not display greater mental rigidity [than healthy controls]

I boxed (in red) statistically significant differences between the healthy controls group and patients with AN, however I’d like to point out that since each trait was measured using different assessments, the actual numbers of each measurement in this table (from Tokley and Kemps, 2007) should be taken with a grain of salt. The statistical significance is more important to this particular study than the scores of participants on each assessment.

After establishing that anorexics have a reduced abstract thinking ability compared to the control and that there are significant differences in preoccupation with detail between the two groups, Tokley and Kemps analyzed the data to determine whether or not preoccupation with detail could account for the difference seen in abstraction. Of the various indicators of preoccupation with detail measured in this study, only field dependence–independence made a significant contribution to poor abstract thinking skills. Even low BMI, anxiety and depression showed little correlation to poor abstract thinking. This is concordant with previous findings that have failed to find a relationship between anxiety/depression or weight and cognitive function.

Regardless of the fact that there was not overwhelming support for the hypothesis that preoccupation with detail leads to poor cognitive function, there is evidence that patients with AN are more detail oriented than healthy controls and that they have reduced abstract thinking capacity. Both of these things, separately, can impact treatment of AN.

…a reduced ability to generate plausible solutions to problems and engage in conceptual thought [i.e abstract thinking] may impinge on the ability of AN patients to appreciate the seriousness of their disorder and fully engage in therapy. Hence, strategies aimed at the remediation of poor abstraction and obsessive preoccupation with detail could usefully be incorporated in eating disorders treatment protocols (Lena et al., 2004).

I know in my experience, being too focused on the details has turned things that are supposed to be helpful into a giant mess. For instance: the meal plan. I firmly believe in having a meal plan and I rely on that structure. But I am learning that I have to let go of some of the details and look at the big picture. I have spent numerous dietary sessions arguing about what the measurement of some exchange is, it’s almost more disordered! The meal plan is a good guide, but at this point in my recovery, I need to let go of some of the nitty gritty. This is where abstract thinking would come in handy — if I could conceptualize more than one dimension of the meal plan (i.e beyond “right or wrong”), I could wrap my head around letting go of some of the details.

This is just one example, but my point (and the end line of this paper) is that whether or not there is a cause/effect relationship, cognitive deficits and obsession with detail both play a role in AN and in recovery.

References

Tokley, M., & Kemps, E. (2007). Preoccupation with detail contributes to poor abstraction in women with anorexia nervosa. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 29 (7), 734-41 PMID: 17896199

I would be really interested to see how a similar study played out with OCD. I suspect there could be similar results.

Great article, Gina. My one annoyance is that the subtypes of AN are not differentiated in many of these studies. Although a majority of people with AN have the AN-BP subtype, much of the literature (particularly in areas of neuro- and cognitive science) speak to the AN-R subtype but do not refer to it as such- a gross negligence in my opinion. In sum, many of these findings refer only to a very small subset of AN.

Katie: I agree with you, that is a great point. A lot of studies focus on restricting AN *only*, with no history of b/p-ing, or BN. And that may bias the results/not apply to AN-BP.

It’s interesting that there was no correlation to weight, but perhaps there would be a correlation to degree of nutritional deficiencies or length of time with insufficient energy intake. I have noticed this myself as I have been up and down with recovery and relapses, or at times much the same low weight, but at times eating well or at other times restricting.

Also interesting that there was no correlation with Anxiety, but perhaps there would be a correlation with more generalised internal distress, not specifically a diagnosable anxiety disorder. I suspect that internal distress increases the need to narrow focus to detail, to simplify. I have noticed this myself. It reminds me of what I’ve read about right brain vs left brain type functions. ‘Right brain’ sees big picture, thinks abstract and is more emotional. ‘Left brain’ thinks linear, is more verbal. That may help to explain the benefits of other therapies like art therapy and movement therapy that get both sides of the brain working together. The theory is that we can quite naturally reduce the connection between left and right hemispheres, shutting feelings out and overutilising left brain processes, sometimes to our disadvantage.

I’m quite sure that the two of these mechanisms could work together – undernutrition and deferring to left brain processes and each one could worsen the other.

Thanks for a good topic, Gina.

I was surprised, too, that there was no correlation with weight/BMI. But, like you said, I think it has more to do with nutrition and less to do with weight (they do always say that it’s not about weight! ;] ). I know for myself, too, that when I’m undernourished at any weight, I can be a total cognitive mess.

I think that there probably is some relationship between detail oriented/obsessive behaviors and anxiety (although, still only speaking from personal experiences). The way this study analyzed their data, they didn’t really screen for that but it would be interesting to look at for sure. I am continually intrigued by the role of anxiety in my disorder/behaviors.

Thanks for reading =]

If what you’re saying has any effect, the wouldnt we be able to get a better insight in other disorders/behaviors.If peoples mental processes are messed up in some sort of way, can they really be treated with pills, or sessions with people? Or could you control it with practice but always have it there in the back of your mind like people who quit smoking do?

I think that a really common question is whether or not people fully recover or whether or not recovery is a life long process and the answer tends to vary from individual to individual. Given that we know there is a biological/neurobiological component to eating disorders (they’re sometimes referred to as “brain disorders”), a lot of people believe that you’re always fighting the disorder, but learn to live day-to-day without behaviors. On the flip side, many believe that full recovery/mental freedom is possible.

Regardless, therapy and medication can help (in my opinion). Meds can help restore some chemical imbalances in the brain making the day-to-day easier (in my experience). Talk therapy is helpful (although not for everyone), and we know that through repetitive behavior modification, we can rewire neurons/neural pathways (Tetanya would be a better person to talk about that, I think).

Yeah, that was a long reply, but I think the points you raise are common questions that circulate this field. =]

Like everyone else, i too was surprised that they found no correlation to weight. i really was expecting a negative correlation betweeen the two. you would think that as these obsessive behaviors and detail oriented thoughts happened that they (people with AN) would eat less. i believe that anorexia is a brain disorder that can be treated with pills (my opinion)if scientists can find a pill that can treat their anxiety and obsessive behaviors I think those would really help w/ the chemical imbalances. I’m sure that scientists know which parts of the brain produce these intense behaviors and emotions. So it shouldn’t be hard to prescribe something that could at least help. Although i said i think it can be treated with pills, i think that counseling is needed as well to see what underlying issues are causing them to pay so much attention to their body image/weight rather than other things. I also feel that bad things going on in someones life or a tragic experience can cause someone to under-nourish themselves or not eat at all. It could have been a good idea to look at those types of people as well because they sometimes don’t under-nourish themselves consciously. Studying a person who consciously under-nourishes and someone who doesn’t purposely under-nourish themselves would be more helpful to find a drug that could help these types of people. As someone said earlier they shouldn’t have just limited it to one type of eating disorder. i think if they expanded their study to look at AN-BP as well they may get an even better understanding.

also i would like to add that poor cognitive functioning is connected to many diseases eg, mental retardation, certain learning disabilities such as dyslexia,dementia etc. with that being said anorexia is a sickness. i hate when people say that there’s nothing wrong with them (people with AN) and things like they just need to eat more. Looking at this article should further explain to people that it isn’t easy as that for people with this disorder. The way that their brain functions is different from people who eat normally.

I agree that AN is a brain disorder and drugs definitely help treatment. There are a lot of studies that focus on parts of the brain that are specifically affected in people with eating disorder (not just AN), that gives us a better idea of what types of drugs are potentially helpful. I think part of the reason that they couldn’t find a correlation to weight MIGHT be because cognitive function is related to how nourished someone is (regardless of weight). That is just what I’ve noticed in my experience & other readings I’ve done.