Eating disorders don’t discriminate against gender, age, sexual orientation or race. Veteran men in their 50’s can struggle with eating disorders, as can trans men and women of all ages and backgrounds, and so can congenitally blind (and deaf) individuals.

Besides the barriers that many of these patients face in simply getting diagnosed with an eating disorder, yes, even if they’ve passed that hurdle, many face an even bigger problem: getting appropriate treatment.

Naturally, no one treatment method will work for everyone, especially when the patient population is so diverse. What works for a 13-year-old female may not work for a man in his 40’s or 50’s. Unfortunately, treatment options (at least those that have some empirical evidence) are limited. As I’ve recently blogged, new treatments are being developed and utilized in treating adults and/or patients with with long-standing eating disorders – sub-populations that have largely been ignored for a long-time.

Following this trend of broadening the types of interventions available to treat eating disorder patients is UCAN: Uniting Couples in the treatment of Anorexia Nervosa.

Despite the gravity of its chronic morbidity, risk of premature death, and societal burden, the evidence base for treatment [of anorexia nervosa] — especially in adults — is weak. Guided by the finding that family-based interventions confer benefit in the treatment of anorexia nervosa in adolescents, we developed a cognitive-behavioral couple-based intervention for adults with anorexia nervosa who are in committed relationships that engages both the patient and her/his partner in the treatment process.

In reading through this paper (freely available here), I got the sense that although the authors are tailoring the treatment for anorexia nervosa patients, I, personally, don’t see why the exact same approach cannot be applied to bulimia nervosa patients (it is just that UCAN is a better acronym than UCBN?).

The idea is really rather simple. Eating disorders affect everyone who is close to the individual struggling with an ED. This is just as true in the context of the family as it is in the context of a romantic relationship. Caregivers – be it family or partners – are placed in tremendously difficult positions (something I plan to cover in the future). It is hard to take care of someone who has an eating disorder: it is/can be a hard thing to understand, it is very emotionally and financially draining, and it is really easy to inadvertently do or say the wrong thing.

Interestingly, individuals with AN (not sure about BN, but don’t think there’s a reason for it to be different – if anything, probably higher) “enter into committed relationships at rates comparable to healthy peers” (Maxwell et al., 2011). More than that, for patients who are recovered, the relationship often played a “driving force” in recovery (Tozzi, Sullivan, Fear, McKenzie, & Bulik, 2003). Of course an unhealthy or hostile relationship can do more harm than good, but, the evidence that individuals with eating disorders enter relationships and that these relationship can play a crucial role in recovery provides a great opportunity to develop a treatment program to aid couples in recovery.

UCAN is not meant to be a stand-alone approach to treatment, per se, but should be, in optimal situations, used in conjunction with medical treatment, nutritional counselling, and individual therapy.

As an augmentation therapy, and unlike family-based treatment for adolescent AN, partners are not asked to take responsibility for monitoring patient weight and eating. This developmentally appropriate approach avoids power imbalances that could emerge if the partner were in a position of complete authority.

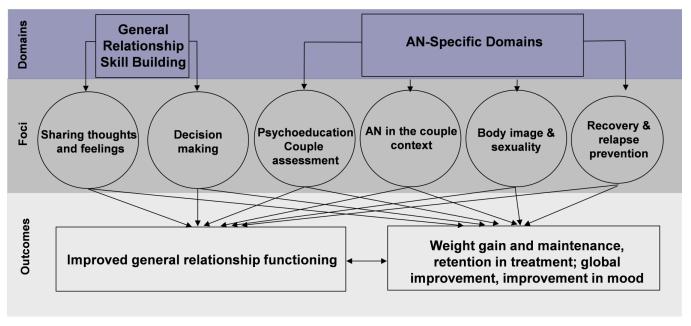

THE UCAN MODEL: (click on image to enlarge)

The UCAN model has three phases:

PHASE 1: FOUNDATION

- understanding couple’s experience with AN

- education about AN and recovery process

- teaching effective communication & problem solving skills

PHASE 2: ADDRESSING AN in a COUPLE CONTEXT

- attaining a healthy body weight and healthy eating behaviours

- tailored for each couple, based on assessing major challenges and how to respond to them effectively

- resolving how to best deal with body image and sexual issues and move past them

PHASE 3: RELAPSE PREVENTION + TERMINATION

- developing effective responses to deal with relapses and slips

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS FROM THE DEVELOPERS OF UCAN

The development of UCAN resulted from a collaboration of eating disorder researchers (Cynthia Bulik) and couple researchers and therapists (Donald Beacom and Jennifer Kirby). They provide personal reflections about their experiences. Dr. Bulik’s are particularly illuminating and so I’m going to quote her at length:

Historically and typically, partners are not systematically included in the treatment of adults with AN… Often family sessions are tailored more for parents than partners, and they inform rather than engage. The partner may be enlisted in times of crisis, to assist with financial matters, or for instrumental support; however, typically they remain in the dark about the complexities of the recovery process.

Not including partners in treatment perpetuates a culture of secrecy and maintains “no talk zones” around many aspects of the eating disorder. In many ways, allowing this secrecy to continue colludes in maintaining the disorder.

In developing and piloting the UCAN trial, it became clear how poorly informed partners were about the illness. Many believed their loved ones were choosing to starve and failed to appreciate the underlying biological aspects of the illness … had preconceived expectations that recovery would be linear and had great difficulty appreciating … that recovery from AN was anything but a linear process … Partners clearly appreciated the gravity of the illness and feared for the patients’ lives, but they were often cornered into positions of learned helplessness, unable to find strategies or approaches that could “get through” to their loved one.

Traditional approaches in which the partner was not included are clearly highly frustrating and confusing for partners. The patient is hospitalized, in residential treatment, or in outpatient treatment, and none of the details of the therapeutic work is shared with the partner. The partner does not know when weight is increasing, when exchanges are being skipped, what is enough exercise, etc. They are effectively shut out of everything related to the eating disorder which permeates most aspects of life and have no idea what is therapeutic and what is not. Without guidelines partners remain deeply fearful that no matter what they say, they will do harm….

A useful parallel to consider is a patient with diabetes. Imagine if the partner had no information about what caused diabetes, what was an appropriate diet, when insulin or glucagon was required, and what a diabetic crisis looked like. The partner would live in constant fear and be ill-prepared to deal with the medical crises that would emerge if the patient was non-compliant with treatment recommendations. With no point of reference or anchor in “normality,” partners of individuals with AN simply have no idea what patients need to eat to maintain weight, how they need to curtail exercise, or how damaging laxative use can be, for example…

Partners also sacrificed their own health for the well-being of the patient. Many partners gained weight as they attempted to “eat with” the patient, hoping that this joint activity would encourage her to eat more. Others stopped exercising because the patients would be envious of their time at the gym or compete for who exercised more. Other partners became completely exhausted.. We have done a disservice to partners for years by not appreciating the magnitude of their co-suffering and proving them with a blueprint for dealing with AN….

Unlike other forms of psychopathology in which the patient is eager to achieve symptom remission, individuals with AN desperately cling to the starvation state… many believe this is because food restriction and exercise serve an anxiolytic role in these individuals who tend to be temperamentally anxious and dysphoric. Our treatments and the weight gain that entails, rather than leading to a greater sense of calm and decreased anxiety, actually can increase anxiety and dysphoria until other approaches at emotion regulation can be effectively implemented. We have observed that engaging the partners in treatment is clearly associated with lower drop-out.

Their presence can help the patient keep her [his] “eye on the prize” and weather the temporary discomfort and recrudescence of anxiety associated with renutrition and weight gain with an eye towards biological normalization and the eventual ability to manage anxiety and dysphoria by more effective means than starvation. There were many points during the UCAN clinical trial where, had patients been in individual therapy, we may never have seen them in the clinic again. But the partners, after already putting so much effort into team recovery, played an active role in keeping the patients in treatment.

MY OWN THOUGHTS

Of course this approach is not going to work for every couple – but no single approach will ever work for all patients. The goal, now, is to determine which couples will benefit the most from this treatment approach as well as tailor it for bulimia and binge eating disorders.

The authors conclude by reiterating that the current state of treatment for adults with AN is “unacceptably poor” and “treatment drop-out is exceedingly high”. New approaches need to be developed and tested, urgently. I’m excited to see the results from large trials of UCAN and, if shown to be efficacious, even for a subset of patients, seeing this approach become more widely accessible.

For me, personally, my partner is the single most important person in my recovery process; working together has been crucial. So I’m really excited about this, actually, because I think it has a lot of potential to help (at the very least) a subset of individuals with EDs. As a couple, I’m confident we would’ve benefited from something like this – particularly on his end, to better understand the ED and recovery process, and relate to others in similar situations. But, we benefited from many other factors specific to our situation. I’m not going to go into details here, but, feel free to email me privately, if you are interested in more details.

(Apologies for the dearth of posts in the last few days, I’m still – and will be for a while – focusing on writing my thesis and defending soon.)

References

Bulik, C.M., Baucom, D.H., & Kirby, J.S. (2012). Treating Anorexia Nervosa in the Couple Context. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26 (1), 19-33 PMID: 22904599