It is a relatively well known fact that eating disorders have a high relapse rate and many people, myself included, find themselves in multiple intensive – residential, inpatient, even partial hospitalization – treatments. One may ask if such intensive treatments really work or if long term intensive care is just a band-aid of sorts. I know I’ve had to ask myself, “why is this going to work this time when it hasn’t worked in the long run before.”

There is even debate in the field on whether residential treatment actually has evidence supporting its effectiveness (see Tetyana’s post here). I can speak from experience that the various intensive treatments I’ve personally done have saved my life and given me more perspective, skills training, and support than I could have had otherwise. However, despite having made significant changes, I’ve had more than my share of slips and relapses.

I am willing to bet I’m not alone.

Maintaining change after intensive treatment is a little-discussed topic. (Although it’s pretty important, I think. I mean, making the changes is difficult, but the changes need to be sustainable if the work is going to be worth it!) Cockell and colleagues explored the topic in their 2004 paper.

The article begins by acknowledging the common concern that both patients and treatment providers have when an intensive treatment comes to an end, which is: how does the patient maintain the changes that were made during her treatment [note: this article speaks only of females, I personally am not making that judgement] in an outpatient setting. Despite motivation, there is question about the patient’s “ability to choose non-eating disorder coping strategies when her[/his] distress level runs high.”

Furthermore, the transition from treatment to “real life” is inherently destabilizing and stressful, which almost seems to set the patient up for high-risk situations. Thus, “learning more about this critical phase of change [i.e the maintenance of change] is important, as relapse rates in the eating disorders are reported to range from 33% to 63% (Field et al., 1997; Herzog et al., 1999; Keel & Mitchell, 1997; Olmstead, Kaplan, & Rockert, 1994), and repeated admissions to treatment programs are common (Woodside, Kohn, & Kerr, 1998).”

The authors go on to cite several challenges in treating eating disorders that lead to high relapse and readmission rates. These can be grouped into three categories:

- Eating disorders are mental disorders with physical consequences, as such the coordination of mental and physical care is necessary or optimal treatment, however integrated care is not always available outside of an intensive treatment setting, and this may lead to poor prognosis.

- Comorbid disorders (such as anxiety, depression, PTSD) complicate and impede treatment of the ED

- Many patients with eating disorders feel ambivalent toward recovery. Despite negative consequences of the disorder, EDs can serve as a coping mechanism, and in pursuing recovery, the patient loses not only the negative aspects of the disorder but also the functional value of it (which can be quite high).

SO, WHAT WORKS?

Although recovery from an eating disorder is an enormous challenge, many individuals do attain partial or full recovery. While it is well understood that the course of recovery from an eating disorder is slow, what remains unclear is an understanding of what factors support a favorable outcome.

A small number of studies in the past several decades shed some light on this, but the work, which is dated anyway (from the late 80s to the early 90s!) most definitely left room for further investigation. And so, the present study aims to “identify factors that help or hinder the maintenance of change and the ongoing promotion of recovery during the critical 6 months immediately following eating disorder treatment.”

Cockell et al studied 32 women who had been admitted to (and completed) a 15 week residential treatment center (mean age 27.9 years (with a standard deviation of 10), mean duration of eating disorder was 11.6 years (with a standard deviation of 9)). Diagnoses were made by a clinical psychologist according to the DSM-IV. Prior to treatment, 21 women met diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, and 11 met criteria for an eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS).

Immediately following completion of the treatment program “all 32 reported a decrease in eating disorder symptoms but continued to meet criteria for an eating disorder not otherwise specified [italics mine]”

Specifically, most women had reported reduced behavioral symptoms (including maintaining an objectively healthy weight; no participants met the diagnostic weight criteria for AN) but not reduced cognitive symptoms, thought patterns, and so on..

This isn’t too surprising as the treatment center in this study (as with most others, in my experience) impose weight/behavioral guidelines that are generally adhered to at the facility and cognitive changes are slower to occur (and require, in my experience, more extensive/different/long-term work to change).

Six months after treatment was completed, the diagnoses were reassessed.” At that point, 5 women met diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, 1 met criteria for bulimia nervosa, 21 met criteria for EDNOS, and 5 no longer had an eating disorder diagnosis.” These numbers are consistent with what is generally observed in studies looking at partial recovery, full recovery and relapse (Strober et al., 1997).

To find out what helped or hindered recovery for the women in this study, in-depth, open-ended interviews were conducted with participants in which they were asked to identify what assisted or sabotaged their recovery, in their own words.

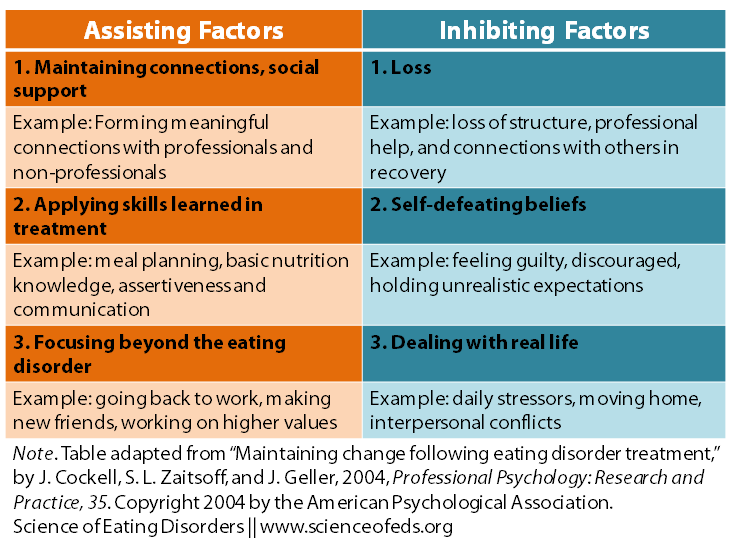

Analysis allowed the responses was broken down into specific factors, summarized in the table below.

Cockell et al break their findings down into three working categories: effective coping, social support and higher values. They further go one to provide treatment recommendations on how to incorporate their findings into outpatient treatment to facilitate the transition from intensive treatment to real life. Their recommendations are valid and seem to follow accordingly based on their results.

The basis of most of their ideas seems to be: have a treatment team that communicates with each other, encourages and facilitates building effective social support, helps prepare you for times of distress and works with you on building a life outside of the eating disorder that incorporates values you hold for yourself.

If you’re like me you may be thinking that this sounds like good practical advice based on first-hand accounts of research. You also may be thinking DUH. I’ve, personally, been in solid treatment programs that have incorporated everything mentioned in this study and beyond. I also have a treatment team (currently and in the past) that is well versed in eating disorders, communicate well with each other, with me, AND with my former treatment center(s).

I’ve also relapsed and gone back to treatment. In spite having all of this in place. (And I’m aware that no one on this project said that this is a fool-proof plan, but hang in there with me for a second.)

Although this study is valid, it fails to mention something pretty significant (in my opinion): in order for everything that they cite as “helpful” to in fact be helpful, the patient has to fight for it. Fight really hard. For example, having a treatment team that works with you on interpersonal skills and building meaningful relationships isn’t going to help if the patient doesn’t get out there, be vulnerable and do the work it takes to build relationships. Same with nutritional counseling and coping skills. I learned a lot of things in treatment and I continue to learn a lot of things that would be very helpful in maintaining recovery. For instance, I know that meal-planning is helpful. I know the importance of nutrition. I also know that getting through the anxiety, time and energy it takes to do the plan and eat is sometimes huge. I know I’m not alone.

Bottom line: I certainly think that everything Cockell et al report is useful. But I also think that another HUGE problem in maintaining change coming out of intensive treatment is doing the recovery behaviors long enough so that they become habit, less of a job, more of a way of life. This research cites one way in which that can happen which involves the support of others, but misses the other side of the coin that involves the work the patient must do themselves.

What are your thoughts, SEDs readers?

References

Cockell, J., Zaitsoff, S.L., & Geller, J. (2004). Maintaining Change Following Eating Disorder Treatment Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 35 (5), 527-534 DOI: 10.1037/0735-7028.35.5.527

Good topic. I agree that fighting for recovery is crucial. In order to fight, we need a whole lot, like the skills, the motivation, the hope that it will be worth it and a cheer squad/advisory board/treatment team helps a bit too.

I often wonder if intensive treatment takes the patient too far too quickly. In my experience, the treatment team asserts that the best model of treatment is to get me to 20bmi, with inpatient then intensive outpatient care, in the space of 4 or so months, and then it’s discharge and cross fingers that I can maintain the weight and the eating pattern. Of course they taught me skills etc.

This puts a lot of pressure on to maintain recovery. It’s a lot of change in a relatively short space of time, in an environment unlike home and normal life. And the change has been created by the treatment team and not by choices that I’ve had a great deal of say in.

I’m sure that approach is quite ok for some patients.

I wish the pace of treatment could be more variable, rather than ‘one size fits all’, where the patient is involved in goal setting. In this way, recovery could be intentionally staged, ie. progressive in stages. Assuring of course, medical stability. One way this would help, as I see it, is increasing confidence in one’s ability to consolidate progress and reducing feelings of failure and discouragement from not being able to meet overly high expectations.

Anyone else ever thought this kind of approach would help?

I agree that having flexibility in the pace of treatment could be really beneficial. I think in residential, inpatient, php, iop etc, a lot of the pace is determined by insurance (i.e. why should we pay if progress is going so slowly). When there’s a time limit, I think Tx centers want to do as much as they possibly can, which is usually physical =/

I experienced a *little* more flexibility in residential this time … not at all with weight restoration which went at a ridiculously fast pace, but in terms of integrating other recovery behaviors. Also, DEFINITELY having a team that is encouraging/believes in your ability to do it.

The biggest lesson I learned in treatment this time was after I purged and told the RD at the treatment center. I was expecting to be put on some crazy observation or something and I was already pissed at myself for doing it. She said something along the lines of, “If it wasn’t relieving in the same way it used to be, then I’m sort of glad you did it, what a great lesson to learn in a safe environment. You need to be able to make mistakes and learn from them in a safe way.”

I was mind blown. That I could process a slip and not get in trouble for failing was huge. It also was kind of a red flag that I needed to have more support from staff/my therapist etc. We definitely need more of that.

I think there sound like there are huge differences in treatment here in Australia to other countries, so my experiences probably won’t be the same as others. But for me, it’s been a vicious cycle. The more inpatient treatment I’ve had, the sicker I’ve actually gotten all round. And this cycle just kept feeding itself for years, a pretty horrible situation.

Treatment in Australia seems to be more in theory than in practice. Apart from the scary shortage of actual beds for people with ED, if you manage to get in, you will find yourself looked after by a large percentage of staff who don’t know the first thing about eating disorders, and find you frustrating, because the ED unit will be a few beds on a general ward and short staffing/funding means they do need to use general staff, take them aside and give them a few (quickly forgotten) general pointers and consider them trained ED staff.

Lack of staff and funding also means that program content doesn’t happen. The programs I’ve been on mostly ended up having more than half their scheduled groups become video watching sessions (in order to ‘babysit’ the patients in after meal time by keeping them in one place but not having the staff to actually engage with them.) Any groups that do happen, there is no continuity and if you a repeat patient as many are, you do the same groups several times over.

And then there is the factor of being ‘forced’ to be there. In public hospital units in Australia, it seems these days that pretty much everyone there has been forced there under the mental health act. That makes for a unit full of angry people there against their will with their minds set on fighting the treatment any way they can – the attitude of the patients can often get very ugly and anti-authoritarian, groups are openly scoffed at and participation rates very low (and rudeness factor high since they still have to be in the group even if they are refusing to engage.)

My hospital has a good meal support program now – and by ‘good’ I mean very strict with all avenues of cheating limited. But I’ve never felt I’ve learnt how to eat ‘appropriately’ there because the meals are on a whole, much larger than would be normal since we are all on weight gain regimes, also there is the feeling of being held hostage because you have less than 20 minutes to eat every bite on your tray or you will drink your entire prescribed supplement. Even for one bite left. You aren’t listening to your body or tasting the food, you are shovelling it in like a robot and racing against the clock. My own treatment meant I mostly ate in bed – and I felt that I was completely clueless as to how to feed myself when I returned home, and clueless as to how to cope out there in the big overwhelming world after another few months on bedrest in a little white room.

Every unhelpful and even deadly behaviour I’ve learnt has been from fellow patients or dreamed up in reaction to something imposed by staff.

I’m not blaming my treatment for how sick I became, I have only myself to blame for that, but I sincerely do not think inpatient treatment is good for people with eating disorders unless they are critically ill and need urgent stabilisation. I think transition house style treatment and day patient treatment would be the best way to go, try to keep people as engaged in the real world as possible, doing as much for themselves to practice valuable skills as possible, and to avoid their whole world and group of social contacts from diminishing into an ED world. the more disengaged we become from real life and real people, the harder it is for us to get out there and be part of it and that in turn negatively affects the patient’s chances of freeing themselves from the disorder.

I definitely think this is geared toward treatment in the states (although I guess I’m not too well versed on international treatment besides, like, the UK). Anyway, just from personal experience my treatments here have been vastly different than what you described, but mostly because I think I’ve been lucky enough to have some treatment providers that were/are very-well versed in eating disorders…I know that revolving-door of Tx exists here too, especially when you enter the realm of psych ward/inpatient treatment. I do think, despite having subjectively “good” treatment, some things remain. I definitely also learned a lot of behaviors from fellow patients and became much MUCH more sneaky after playing games with staff during my first couple of intensive treatments.

You say it pretty well…the most effective things I learned in treatment were how to put a meal together for myself. (In residential, we cooked/prepared a lot of meals for ourselves in an actual kitchen, very helpful). And also, having the opportunity to follow a meal plan with treatment support AFTER I had restored weight. Eating a normal amount of food is still hard, but it’s REALLY different from weight restoration amounts.

Really interesting differences (and still similarities in outcomes despite some really big differences in Tx approach).

Cheers.

This is the one of the major faults in a system that limits or denies access to treatment resources until the patient is severely ill. By the time they reach that point, it is almost impossible to expect patients to participate in treatment in a meaningful way, from

what we know about eating disorders and the effects of starvation on the brain. Hence setting the program up for failure and the individuals for recidivism and relapse.

This article supports my 31 years of experience in successfully treating those with eating disorders into recovery.

Throughout my entire career working with ED Clients I have been aware of several important facets to the real recovery process. 1) as research states recovery from an eating disorder takes from 3-10 years! 2) It is my belief that while there is a need for inpatient treatment – PURPOSE: Primarily to stabilize life-threatening out of control behavior associated with the ED – Period. 3) A long-term group therapy course + individual care as needed allows for the establishment of invaluable healthy relationships/support that focuses/addresses the cognitive distortions/faulty thinking clients present with. 4) This type of group provides a safe environment for the client to try new social behavior such as setting boundaries, new ways of thinking, finally addressing the SHAME that underlies all disordered eating behavior and ALL the though process distortions. 5) Ultimately our clients display interesting and universal outcome – ED behavior simply melts away w/o the constant ‘battle’ described by clients. (Yes I did just say our clients symptoms simply fade away!) 6) During the course of treatment our clients learn effective coping skills for life’s challenges, attain a healthy support group of people, are able to learn to express themselves and their feelings within a very emotionally safe environment!

After 31 years of research, education & experience this has been the MOST SUCCESSFUL method of treatment for these life-threatening disorders! So I whole-heartedly agree with the this article’s main positions!

P.S. Our program meets 3 evenings a week for 3 hours and provides text and phone support between sessions. It also provides dietary assistance and weight monitoring weekly with RD, and involves 3 therapists with well over 50 years of combined experience treating EDs.

All this allows for the client to maintain their life within the world and the recovery process.

Wow, that’s very impressive. If you (EDRC) keep records/stats on patient outcomes or have published your findings, I’d love to see them – and we at SEDs would be happy to review and write a post on them!

I’m curious as to what percentage of your clients are in a position (have the financial resources/insurance coverage) to complete the full course of treatment as described above, if you happen to have an estimate.

We have the outcome studies on the website. Additionally there is a video of clients talking about the recovery process with us. http://www.addictions.net

Our clients primarily use insurance companies – so 100% of our clients are able to afford the treatment. We have made sure that we are in-network providers for most insurers. Additionally, the drop down level cost is ridiculously low and still provides the very same treatment. Making treatment affordable has been one of our mission statements goals.

Thanx for the response I have dedicated my entire career to achieving several goals and have been fortunate enough to attain them. It’s wonderful seeing someone become able to take back control over their own lives.