Is there an association between socioeconomic status (SES) and mental health literacy? Can we predict the extent of an individual’s knowledge about mental disorders based on how much money they make, how much education they’ve received, or how far up the career ladder they’ve climbed?

That is the question that Olaf von dem Knesebeck and colleagues attempted to answer in a paper published recently in the journal Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology.

The authors interviewed 2,014 men and women, residents of two German cities Hamburg and Munich, using a telephone survey. The split is roughly 50/50 between men and women respondents and the mean age was 47.5. The authors presented each interviewee with two vignettes out of three (one on depression, one on schizophrenia, and one on eating disorders).

The gender in the depression and schizophrenia vignettes was varied 50/50 between male and female patients, but all vignettes about eating disorders (one on bulimia, one on anorexia) were about female patients. After reading the vignettes, the respondents were asked to identify the disorder, in an open ended question, then more specific questions (prevalence, treatment, etc..) were asked in a “yes/no” or a scale format (not at all >> very likely).

They assessed SES in three ways:

- highest level of education: “highly educated” meant upper secondary or higher (44.3% of respondents)

- occupational position: “leading” or “supervisor” position was defined as high (48% of respondents)

- household income: 1,500 Euro equivalence income (dividing total income by dependents, 1.0 for respondent and 0.5 for any additional person) was considered high (55% of respondents)

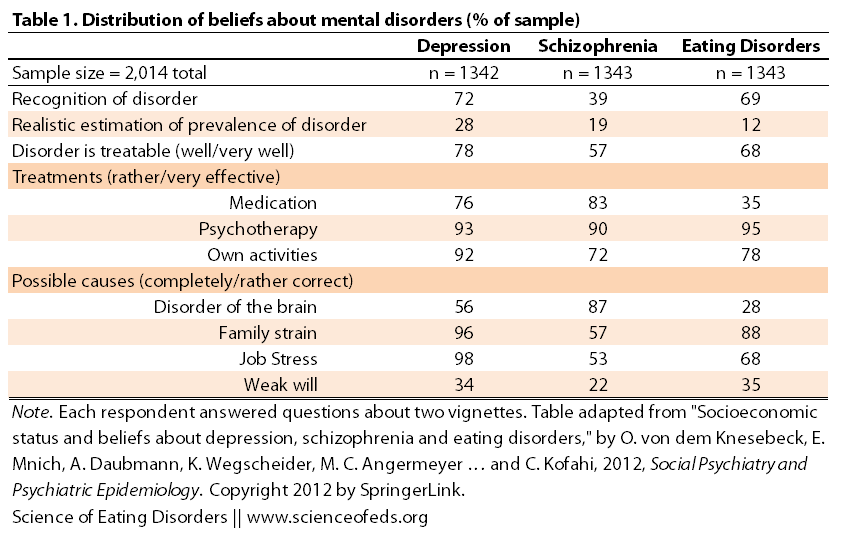

So, without taking into consideration the SES for now, what did they find? Since each person answered only two vignettes there are 1342-1343 responses for each of the 3 mental disorder cases. The numbers are % that either got the answer right or selected the option as a useful treatment or possible cause:

You might be wondering what the authors considered a “realistic estimation of prevalence”: based on other studies, they deemed “realistic” to be 10-25% for depression, 1-2% for schizophrenia and 1-2% eating disorders.

Keep in mind, this means that roughly (assuming this sample size is representative of the population at large, and it may not be) 10-25% of the respondents have or have had depression, 1-2% have schizophrenia and 1-2% have or have had an eating disorder. Moreover, you’d predict that even if they haven’t personally experienced any of these (and of course, there could easily be overlap, one individual could have all 3 and thus be counted in all three statistics), many surely know someone who has experienced at least one of them.

The authors, unfortunately, didn’t assess this, though I think it would be interesting to see just how different (if they are different at all) the numbers are for individuals who haven’t experienced a mental disorder/don’t know anyone who has, and for those who have or know someone close that has. I’m not sure if this has been done previously, I haven’t looked. Anyone?

There are a lot of interesting points in Table 1. Unfortunately, ~30% and ~50% of respondents think eating disorders and depression are disorders of the brain, respectively, while ~85% think that schizophrenia is a disorder of the brain (which is progress, at least we are no longer blaming mothers for schizophrenia!)

But still, huh?

Maybe I’m just deep in my neuroscience specialization bubble, but, all behaviour has a neurobiological underpinning. Maybe the respondents are opposed to saying it is a disorder? But I somehow doubt that. Everything you do is the result of specific brain activity. Yes, genes and the environment can influence brain development and function, but feelings, emotions, actions, thoughts, and the internal of your appetite, sleep schedule, hormone release, etc.. happens at the level of the brain.

The only times that’s not true is in cases where, for example, you can’t walk because your muscles have atrophied or you broke your bone, not because the motor cortex in your brain is not functioning, or because those neurons can’t send a signal to the muscles to move. Then, it is not due to a problem in the brain, but otherwise, whether you decide to call it a disorder, a personality quirk or a variation of normal behaviour: it is coming from the brain, and that activity in the brain is the result of genetic and environmental factors.

Moving past that, I think it is interesting just how high the percentages are for other potential causes, 96% for family strain and almost 98% for job stress, for depression, slightly lower numbers for eating disorders, and in the 50’s for schizophrenia. A good 1/3 think “weak will” is a potential cause of depression and eating disorders, and 1/5 think that for schizophrenia.

To be honest, I’m mostly surprised that 1/5th think that’s true for schizophrenia not so much that 1/3 think that for the others. But, how can 87% think it is a disorder of the brain and 22% also think it is due to a weak will? I wonder what the people that picked both were thinking?

Also interesting is how many think psychotherapy is an effective treatment for all three disorders: in the 90’s! I’d like to see an option for interdisciplinary treatment or something for EDs because that’s important. I mean, I’d have a hard time with that question, I would either pick all or none! Medication can be helpful, but so can psychotherapy, own activities, and a treatment team. But are any of them “very effective”? I don’t know…

What happens when we look at the responses of those in with a high socioeconomic status, as evaluated by the three measures (education, income, occupation status)?

Socioeconomic Status and Beliefs About Mental Disorders

Common trends for depression, schizophrenia and eating disorders:

- high education status was associated with an INCREASED likelihood of correctly recognizing the disorder and its prevalence, in addition, for depression, high income and high occupational position were also associated with a realistic estimate of prevalence rates

- high education status was associated with an INCREASED likelihood of selecting medication as an effective treatment for depression and schizophrenia and a DECREASED likelihood of selecting medication as an effective treatment for EDs

- high education status was associated with a DECREASED likelihood of selecting “family strain”, “job strain”, and “weak will” for all three disorders

Other notable findings

Schizophrenia

- individuals with high education status were significantly MORE likely to select “medication” as an effective treatment and significantly LESS likely to select “own activities” as effective

- individuals with high occupational positions were MORE likely to select that the disorder was very treatable

Eating Disorders

- individuals with high income were LESS likely than others to agree that the disorder is very treatable

- individuals with high occupational positions were LESS likely to select “own activities” as an effective treatment and MORE likely to pick “psychotherapy” (the high education group were least likely to select this)

So what do we make of this?

The authors conclude that these findings illustrate that those with low SES know less about the prevalence and symptoms of depression, schizophrenia, and eating disorders. Moreover, they are also more likely to attribute “weak will” as a possible cause of these disorders.

In terms of variations according to the SES indicators used, associations of beliefs about mental disorders with education are stronger and more consistent than with income and occupational position… occupational and income inequalities in beliefs about mental disorders are largely due to education.

Their findings seem to be in line with previous studies that have also identified that higher education is associated with a decreased likelihood of blaming the individual as being “weak willed” for the fact that they are struggling with a mental disorder.

As always, I’d like to point out the limitations of the study so that the findings are understood in context:

- 51% of those that were called agreed to participate, which brings into question: is there a selection bias? In other words, is there something particular about individuals that agreed versus those that declined, with regard to their understanding of mental disorders or anything that may impact their mental health literacy status?

- Can the wording or content of the vignettes bias the results? As the authors write, “it is possible that the respondents have a notion of mental disorders that differs from the scientific conception… this has to be kept in mind when interpreting their beliefs about the causes, symptoms, prevalence and treatment..”

- The other big problem I see with this study in terms of its utility in evaluating the relationship between SES and mental health literacy is that for many of the questions, we don’t really have or know the answer. So, how can we evaluate if someone else is literate in the subject matter, when, we ourselves don’t have a good idea of what is true and what isn’t. (Specifically for treatment.)

- Moreover, when the respondents select the possible “causes”, they may be interpreting the word “cause” in many different ways: is it a trigger? or is it enough to precipitate the disorder without any neurological or genetic predispositions? is it a contributing factor for the majority of the patients but a small one nonetheless (common but not the most predictive)? Are they just selecting factors that are typically associated with the disorders?

In any case, the findings are interesting and can play an important role in shaping policies aimed at promoting mental health literacy and decreasing mental health stigma among people with a low SES. This study is actually part of a bigger project on mental health in Hamburg (“The aim of the project is to promote mental health today and in the future, and to achieve an early diagnosis and effective treatment of mental illnesses”), so I’ll definitely be follow-up with this project to see how successful it is in achieving its goals.

And just to be on the safe side, I’ll be absolutely clear: This is not, ever, meant to imply that individuals with a low SES are dumber, lazier, more ignorant, etc.. than those with a higher SES. There is no judgement here, moreover, there is no attempt to really understand why this is the case. It is just a study to see if there is a trend, and if there is, will this be useful for planning policies.

SEDs readers, what do you think? Did anything surprise you or is it same old, same old?

References

von dem Knesebeck, O., Mnich, E., Daubmann, A., Wegscheider, K., Angermeyer, M.C., Lambert, M., Karow, A., Härter, M., & Kofahl, C. (2012). Socioeconomic status and beliefs about depression, schizophrenia and eating disorders. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology PMID: 23052428

This is really interesting, thank you. It’s most interesting to me how it’s people of lower socioeconomic status – in these studies at least – who seem less knowledgeable about mental illnesses. I would have thought it the other way around going by my own experience and that of friends of mine, and I’ve found people of lower SES more accepting as a rule – we all have problems, right? But it makes sense that not having the opportunity to learn/hear/be educated would make an impact on their knowledge.

I think there are some things that might be of influence here – just some thoughts (sorry my brain is dumb today so I hope I am making sense)

– people of lower SES might not be financially able to be sick. A lot of them have to power on through it because if they can’t work for eg, they don’t eat, neither do their families. Neither do many of them have the funds to seek help for illnesses, physical illnesses let alone mental, and the mental illnesses would probably be seen as a lesser priority than something life-threatening in a visible physical way.

– and then, with their beliefs about whether their mental illness is treatable – I would imagine that having less access to treatment/funds would highly bias the lower SES opinion.

– It’s interesting how Schizophrenia respondents and ED respondents seem to choose the opposite responses for whether their own activities are helpful and medications are helpful depending on SES. I don’t know what I think about that yet… interesting.

Thank you. I’m sorry I couldn’t say anything more interesting and enlightening!

to clarify, when I said that I would have thought lower SES people to be more knowledgeable even though higher SES people would have had more access to information/education – I guess I felt that people who are better off have more choices about the people they include in their personal lives and can choose to not have to ‘put up’ with those who have a mental illness. Schools for example – are more ‘exclusive’ and difficult to get into. Whereas when you are poorer, the people around you come from all walks of life and all backgrounds, and you can’t really choose where you go and who you are around so easily. Many can’t choose which schools they go to and with school attendance often compulsory, kids with problems would be far more likely to be among the population.

another thing of interest would be the area that people lived in. one area, for example, might have a bit of a ‘culture’ where ignorance prevailed, whereas another area might be more open and accepting, and I think it would be interesting to see how this affects SES/knowledge too.

Hey Fiona:

Your comments are very insightful! And I definitely see your line of reasoning.

I think the fact that schizophrenia and EDs are somewhat opposite, may be because of how most individuals still EDs — that is, now that’s it is more accepted that schizophrenia has strong genetic underpinnings, individuals are less likely to blame the person, and perhaps feel that medication is more likely to work in something that is clearly a “brain things” (both are, equally).

I definitely see what you mean about lower SES individuals being more exposed to hardship and perhaps depression, addiction, etc. and thus be more understanding of it. But, EDs are still viewed as a middle-class white girl thing, which might be why a lot individuals on the lower end of the socioeconomic scale, just don’t “get it”?

Keep in mind, there are a lot of confounds and limitations in these studies. I would be interested if the information was split more along the lines of: one group that either has experienced either of the three disorders or knows someone close that has and another that hasn’t/doesn’t know anyone. Is there a difference in how they answer? If depression affects 10-25% of the population (what the authors here took for prevalence), does that mean that only those who have suffered from depression/know someone who has, got the vignette correct??!?? That’s hard to believe! (The vignettes, by the way, which are in the appendix of the paper, are quite obvious. A few sentences essentially describing someone who is a typical patient, right out of the DSM. Which is, in some ways a problem, too: what if what most people think is anorexia, bulimia, schizophrenia or depression not how it is actually defined in the DSM??)

In other words, what do we define as “literate”?