What is the impact of Western culture on eating disorders? Do images of thin cause eating disorders? I mean, it seems like such a nice and simple hypothesis. It makes intuitive sense: glamorize thin and make thin cool and BAM, everyone wants to be thin. It would be so much easier. Cause? Found. Solution? Easy: ban thin models. Unfortunately (or fortunately for me, since it gives me a lot to blog about) the answer is not that simple.

Just in the last couple of hours, some people who’ve ended up on the SEDs blog have searched:

- does the media cause eating disorders

- thin models on tv cause eating disorders to young girls

- do models influence anorexia

- ultra thin models causing eating disorders

- magazine article eating disorders caused by the media

- and the rare: media doesn’t cause eating disorders

I’m sure most of these search terms lead people to the blog post titled, Does Too Much Exposure to Thin Models Cause Eating Disorders? Anorexia, Bulimia in Blind Women? Since variants on this theme are common search queries, I thought I’d explore this topic a little more. (And there is a lot more to be explored. We are just hitting the tip of the iceberg.)

Cross-cultural research on eating disorders is something that I’ve become a lot more interested in since starting Science of Eating Disorders. Admittedly, I don’t know much about it. (My background is in neuroscience, so I really welcome readers to leave a comment.) But I came across a short and interesting paper comparing eating disorder symptoms in Iranian women living in Tehran, Iran, and those living in America.

The reason I wanted to blog about this study isn’t because I think it is representative (I can’t comment either way on this, I haven’t read enough), but because none of the hypotheses that were made by the authors of this study were supported by the data, and because the findings go against the mainstream and commonly accepted notion that the ubiquity of thin models causes eating disorders.

Yes this is just one study (which means it doesn’t prove or disprove anything, on its own), and other studies have found contradictory results. But because the idea that Western culture plays an important role in causing eating disorders is so prevalent, I want to highlight studies that poke holes in that hypothesis (and this is just one of them).

In this study published more than 10 years ago (“recent” is a very relative term around these parts), Panteha Abdollahi and Traci Mann compared Iranian women living in Iran with Iranian women living in America (specifically, Los Angeles), to “examine the role of Western sociocultural influences on risk factors for eating disorders.”

The traditionalist culture of Iran serves as a contrast to Western norms. Because access to the Western media is illegal in Iran, it is possible to compare women of Iranian descent with and without exposure to Western norms. In addition, women living in Iran are mandated by law to wear some form of [hijab], or full body covering, while in public. Women cover themselves with either the traditional dark full-length veil or with an overcoat that covers the whole body, along with a scarf that covers the hair. These coverings make it difficult to observe the size and shape of the female body, thereby reducing the emphasis on these features and possibly acting as a protective factor against eating disorders or body image concerns. The culture of Los Angeles, in which tight-fitting and body-baring clothes are common for women, provides an ideal contrast to the veiled Iranian culture.

Abdollahi and Mann hypothesized the following:

- women in Iran will have fewer behavioral and cognitive symptoms of eating disorders than Iranian women in LA

- women in Iran be more satisfied with their weight and shape than Iranian women in LA

- the more exposure Iranian women have to Western culture, the more ED symptoms and body image dissatisfaction they will have

- the more acculturated to Western norms Iranian women in LA are, the more symptoms of EDs and body image dissatisfaction they will have

They had 59 female Iranian students living in Tehran (only 4 had been outside of the Middle East) and 45 female students of Iranian descent living in LA, both from large public universities in their respective cities. Those residing in LA have lived in the US for an average of 15 years.

MAIN FINDINGS

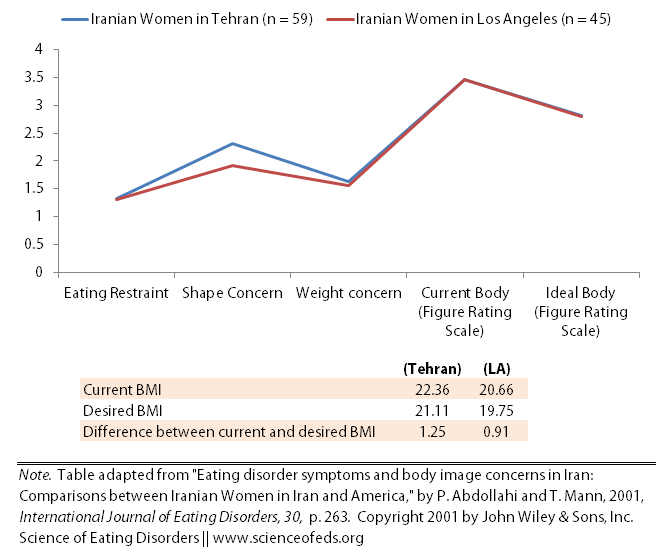

- No differences between the two groups on eating restraint (the extent to which food intake is restricted), eating concerns (the extent of disruptive preoccupation with food/eating) or shape concern (the extent of disruptive preoccupation with shape and degree of importance given to shape) (evaluated by the EDE-Q)

- No differences between what participants picked for “current body” and “ideal body” on the Figure Rating Scale between the two groups

- There was a difference between the current average BMI between each group and the desired BMI between each group, between the difference between current and desired BMI (current-desired) was the same for both

- Current BMI: 22.4 (3.3 standard deviation) for Tehran sample; 20.7 (2.4 SD) for LA sample

- Desired BMI: 21.1 (2.8 SD) for Tehran sample; 19.8 (1.6 SD) for LA sample

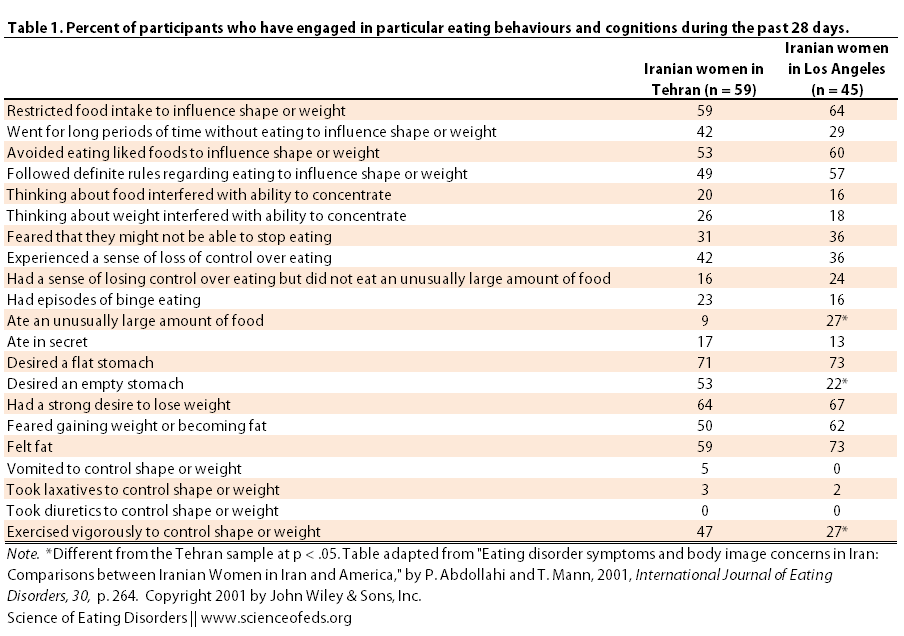

To find out a bit more detail, Abdollahi and Mann took some items from the EDE-Q and asked the participants about the frequency of various behaviours and cognitions in the last 28 days:

Out of the 20 items, 3 were significantly different between the two groups. More women in the Tehran cohort desired to have an “empty stomach” and reported to have “exercised vigorously to control weight or shape” while more women in the LA cohort reported eating “an unusually large amount of food.” Otherwise, the results were remarkably similar.

Now, is there a correlation between the exposure to Western media and disordered eating behaviours and/or body image concerns in the Tehran sample? There were two main ones: women that reported more exposure to Western media also reported more restrained eating on the EDE-Q scale. Interestingly, interest (not exposure) in Western culture was also correlated with current and desired BMI, such that those who had more interest in Western culture were closer to their desired BMI.

I find these results surprising. I would hypothesize that if the more exposure women had, the more they would be restraining their eating, that the more interest they had, the larger the difference between their current BMI and desired BMI (in other words, I’d think the desired BMI would keep being shifted downward).

Is there a correlation between acculturation and disordered eating behaviours and/or body image concerns in the LA sample? Acculturation was measured in two ways: (1) years in the US and (2) language use/comfort using a 9-item scale. No differences were found between either measure and “BMI, desired BMI, difference between current and desired BMI, FRS drawings or either of the three subscales of the EDE-Q”.

None of the three primary hypotheses of the study [were] supported. First, there is no evidence to suggest that college-aged women in Iran have fewer symptoms of eating disorders than college-aged Iranian American women in Los Angeles…

Second, in the Tehran sample, participants who were exposed to Western media did not exhibit more symptoms of eating disorders or body dissatisfaction than participants with less exposure.

Finally, for Iranian women in Los Angeles, more acculturation to Western norms was not associated with more symptoms of eating disorders or body dissatisfaction.

In an epidemiological study published in 2000, Minoo Nobakht and Mahmood Dezkham reported that the prevalence of eating disorders among 3,100 female adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18 was nearly identical to those found in Western countries: 0.9% for AN, 3.2% for BN (a bit higher than reported in Western countries) and 6.6% for partial syndrome (AN+BN).

The most common compensatory behaviors were dieting and excessive exercising: 16.7% used dieting and 15.22 % used excessive exercising to control weight. Also, 1.51% of the total sample reported using self-induced vomiting to control weight, 2.51% used laxatives and diuretics, 2.13% used dieting pills, and 0.25% used drugs to induce vomiting.

The numbers in the second study for excessive exercising are lower than in the first, which may be due to several reasons, including: (1) the larger sample size (and thus more representative figure of the entire population) in the second study or (2) because of the age differences between the women in the two samples.

Nonetheless, all of this means is that perhaps the etiology of disordered eating behaviours is more complex than some would like to believe. And by extension, perhaps banning thin models (or pro-ana) isn’t going to make a big dent in prevalence rates of eating disorders. Which means we need to continue focusing on finding the underlying physiological and neurobiological reasons for eating disorder behaviours. (And it is always important to reiterate that finding biological risk factors is no cause for therapeutic nihilism.)

What are the limitations of these studies?

The studies did not assess eating disorders specifically, just disordered eating behaviours, and all the data was self-reported. It was not formally assessed by trained professionals. The other weakness that the authors mention for the Abdollahi and Mann study is the limited measures of acculturation (just two). It is possible that the lack of differences between the Tehran and LA samples is due to the fact that Iranian women living in LA may still identify strongly with their original culture and not accept or internalize Western norms. (I feel that my wording here is not the best, please do correct me or suggest alternatives if you know what I’m generally trying to say.)

There are other factors to keep in mind, when interpreting this study:

We suggest that this lack of differences supports the claim that issues of Western norms and focus on body are not as central as previously thought in the development of eating disorders. However, it is possible that those issues are indeed critical factors in the development of eating disorders, but the Tehran culture may have other factors that increase the risk of eating disorders or the Los Angeles culture may have factors that decrease the risk of eating disorders. Finally, the Tehran culture might be somewhat different from that of the rest of Iran, just as the Los Angeles culture is somewhat different from the rest of the United States.

What if the authors sampled Iranian women living in rural areas? It is always very difficult to control for all the possible factors in these types of studies, but I do think the contrast between Tehran, where exposure to Western culture is limited and women’s bodies are covered, to Los Angeles, where image is oh-so-important.

Of course, it is important to mention that other studies have found that individuals who have moved to Western countries exhibit more disordered eating behaviours than individuals who haven’t migrated. Abdollahi and Mann list some:

- Fichter et al (1983) found that Greek women living in Germany had a higher prevalence of anorexia, despite having lower rates of figure consciousness, dieting behavior, and preoccupation with eating, than Greek women living in Greece [1.1% versus 0.4%]

- Nasser (1986) found that Arab college students in London [n=50] had more symptoms of eating disorders than Arab college students in Cairo

- Choudry & Mumford (1992) found higher prevalence of bulimia nervosa among Pakistani immigrants living in the UK than in Pakistan

One possible explanation that must be considered is that before the Islamic revolution in 1978, Iran was a highly westernized country and there may be lingering effects of this westernization. In particular, although study participants in the Tehran sample were not familiar with Western culture, they were raised by parents who were. It is also possible that the large Iranian population of Los Angeles somehow functioned as a protective buffer against Western norms for the participants in the Los Angeles sample.

References

Abdollahi, P., & Mann, T. (2001). Eating disorder symptoms and body image concerns in Iran: Comparisons between Iranian women in Iran and in America International Journal of Eating Disorders, 30 (3), 259-268 DOI: 10.1002/eat.1083

Nobakht, M., & Dezhkam, M. (2000). An Epidemiological Study of Eating Disorders in Iran. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28 (3), 265-71 PMID: 10942912