They are crazy stories, really. It is hard to believe they are true.

A 28-year-old woman with anorexia nervosa complained about weakness and nausea following the insertion of a feeding tube. Her gastroenterologist sent her to the emergency room (ER). The woman was in the emergency room for two days without receiving any food. She was discharged home after she was told her lab tests and X-rays came back normal. Unfortunately, her X-rays weren’t normal. Her gastroenterologist determined she had a bowel obstruction and sent her back to the hospital. She lost a substantial amount of weight in those 3 days.

The second story is even worse.

A 26-year-old woman with a feeding tube was discharged prematurely from a residential facility. She began to feel dizzy and weak, and was admitted to a hospital. She did not receive any food for the 6 days she was there, despite extremely low blood sugar levels (half of what is defined as the threshold for low blood sugar). For reasons that are not clear, an order for tube feeding was cancelled and two days after discharge, she returned to the ER with a letter from her doctor stating that “she required medical supervision for the initiation of feeding.” Despite this, she was discharged from the ER within hours. She was re-admitted to the hospital the next day.

How could health care professionals screw up this much? We are not talking about forgetting to do a small and easily overlooked lab test.

No.

What we are talking about is the “omission of an essential therapeutic intervention”: food. “An analogy might be drawn to omitting insulin in the treatment of type 1 diabetes.”

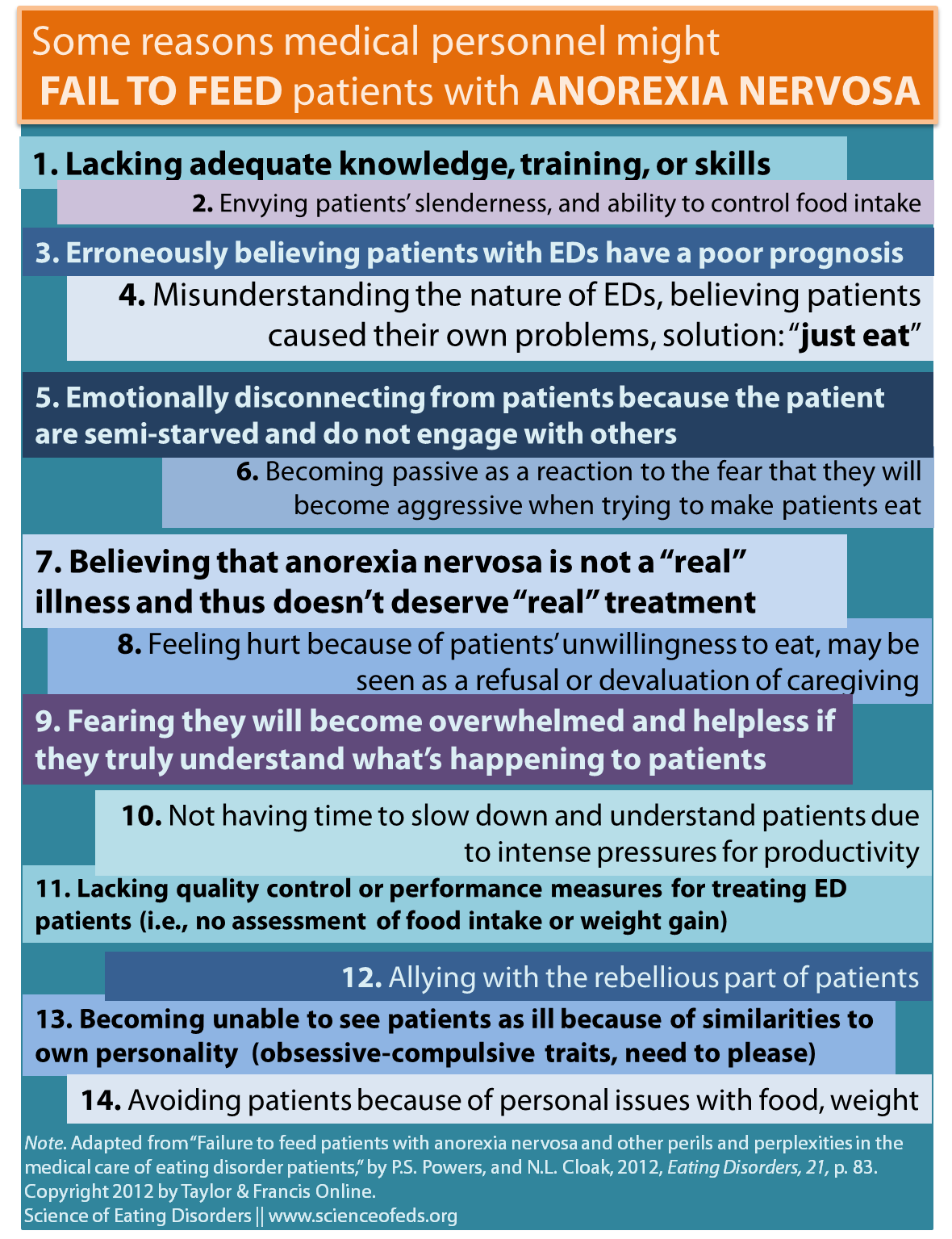

There are a number of possible reasons that, when combined together, lead to these extreme cases of medical negligence. Below is a list ofsome of the reasons that medical personnel might fail to feed, or otherwise care for, patients with anorexia nervosa. This list is taken from a longer list in the paper by Pauline Powers and Nancy Cloak (2012). Some of these reasons might be generalizable to all eating disorders or all mental disorders, whereas others are probably unique to anorexia nervosa.

I think number four and seven are really important. Observing my friends and my partner go through medical school made it very clear for me that, when compared to other facets of medicine, mental health is barely taught. The disparity is striking given that mental health issues affects nearly everyone, directly or indirectly. It is not something reserved for a particular group of individuals deemed “crazy.”

Powers and Clark wrote that when it comes to eating disorders,

Clinicians may not understand the mental processes that interfere with the patient’s ability to eat appropriately. This kind of response may relate not only to lack of information, but also to a kind of collusion with the patient’s denial of illness, or to a misunderstanding of eating disorders as caused by societal pressures for thinness.

There is a tendency–a desire that I think all of us have–to think of physicians and surgeons as always acting in the best interest of the patient. But that’s not always true. It is not true for many reasons, but from the list above, two broad categories appear: (1) lack of knowledge and (2) countertransference reactions.

Countertransference, as Wikipedia defines it, is “a redirection of a psychotherapist’s [or physician’s] feelings toward a client—or, more generally, as a therapist’s [/physician’s] emotional entanglement with a client.”

Think number thirteen or fourteen.

When it comes to knowledge about eating disorders or how to treat them, physicians don’t do so well:

- 42% of primary-care physicians felt they didn’t have the skills to screen for EDs, according to a US survey (Linville, Brown, & O’Neil, 2012)

- 72% were uncertain about how to managed patients with EDs (Linville, Benton, O’Neill, & Sturm, 2010)

- 42% of Ob/Gyn’s in the UK and Australia over-estimated the weight loss required for the anorexia nervosa diagnosis (J. F. Morgan, 1999), and in one UK survey, 53% of primary care physicians thought a BMI of 16 or less was required for the diagnosis of AN (Currin, Waller & Schmidt, 2009)

- 25% thought bulimia nervosa was untreatable (J. F. Morgan, 1999)

Adding to the general lack of knowledge about eating disorder diagnosis and prognosis is the bad reputation that ED patients have among health care professionals. Clinicians and therapists often feel envious, frustrated, and helpless when it comes to treating patients with EDs. Patients are often seen as being weak and manipulative (J. F. Morgan, 1999). The perceptions of nursing staff, therapists, and physicians are similar to that of the general public: patients with anorexia nervosa are not really sick. They are attention seeking, bratty, middle-upper class white girls. Nothing, of course, could be further from the truth.

In 1977, H.G. Morgan wrote in an article titled “Fasting girls and our attitude toward them” about countertransference:

We are of course anxious to feed those who take insufficient food, but if frustrated, our anxiety quickly turns to hostility at what seems to be an unnecessary, self-imposed disease . . . . we need to come to terms with [this] if our treatment is to be more effective than our predecessors.

I’m not in the healthcare profession, and I’m not old enough to know how much things have changed. But I do know that more needs to be done. A lot more.

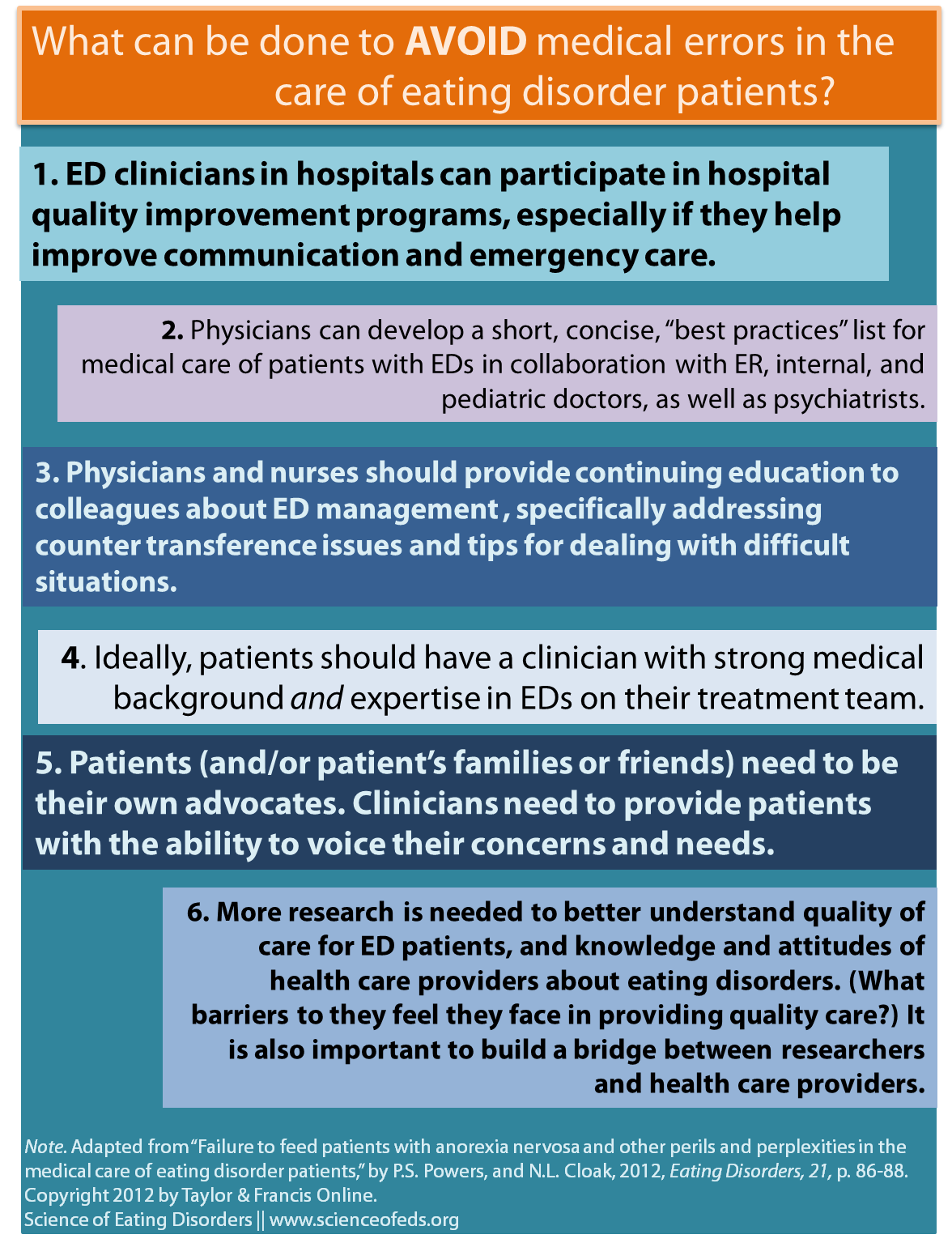

Powers and Cloak provide some advice–tailored not at specific individuals but at health care institutions more broadly–about how to minimize the risk of the medical errors such as those described in the stories above. I summarized their suggestions in the figure below:

This list is just skimming the surface. It is aimed at physicians and health care workers in hospitals or other health care institutions. It is aimed at working professionals and what they can do now. There are many more things that need to be addressed at the training level for physicians, nurses, therapists, social workers, and so on. We need more education for families and carers about how they can work together with their loved ones and the healthcare team to facilitate recovery.

Finally, I think we need to work toward a better public understanding of eating disorders. I want to see more stories about eating disorders in the medicine, health, and science sections of newspapers and magazines, as opposed to the fashion and celebrity news sections.

Naturally (because I write this blog), I think that for better eating disorder treatment and care, we need more research findings to get into the hands of clinicians and health care workers, parents, patients, and the general public. (Of course, these issues are not unique to eating disorders, and I would never imply that they are.)

As an aside, this is probably (99% likely) my last post for 2012. Happy New Year! And as always, thank you so much for reading, commenting, tweeting, sharing, and sending me lovely messages about how much you enjoy the blog. It means so, so much to me!

References

Powers, P., & Cloak, N. (2013). Failure to Feed Patients With Anorexia Nervosa and Other Perils and Perplexities in the Medical Care of Eating Disorder Patients Eating Disorders, 21 (1), 81-89 DOI: 10.1080/10640266.2013.741994

“I want to see more stories about eating disorders in the medicine, health, and science sections of newspapers and magazines, as opposed to the fashion and celebrity news sections.” Absolutely.

Excellent blogging, as always. This one should be circulated to any medical professional who has even the slightest chance of dealing with folk with eds during their career.

Hoping for a happy, well-informed new year for all!

Hi Rufty,

Thanks! I’ll probably write an article for the University of Toronto Medical Journal for their upcoming mental health issue and I think I’ll frame it around these issues. I’m not sure what exactly yet, but, something along the lines of what doctors need to know, maybe what some common misconceptions are, something like that. I think the problem is that many of them don’t think they’ll deal with EDs. They think it is just an issue psychiatrists deal with! So, so, wrong!

Happy New Year!

Tetyana

Another related case is Leslie George. She had bulimia and went to the ER with a perforated stomach after a massive binge. The hospital decided she just wanted them to help her purge and delayed treatment. She died of sepsis the next day. If they had been more open-minded about treatment, she may have survived.

There are too many cases like that or similar 🙁 Way too many.

Thanks for bringing this up, though. I might use some of these cases for an article I’ll probably write for the UofT Medical Journal.

I can put you in touch with Leslie’s parents if you want to interview them. They have been very open about her case.

Amazing! Definitely, I’ll email you?

Happy New Year!

Great topic.

I thought it was bad enough being in Emergency for 12 hours without being fed or even offered anything! It truly is a serious and widespread issue.

At the time I was well enough that I would have eaten something. I feel they’ve assumed that just because I have anorexia that I would refuse any food. Though I do figure it’s normal that food isn’t served in the ED, surely someone’s there for any length of time would be fed, especially someone with an NG tube.

“At the time I was well enough that I would have eaten something. I feel they’ve assumed that just because I have anorexia that I would refuse any food. Though I do figure it’s normal that food isn’t served in the ED, surely someone’s there for any length of time would be fed, especially someone with an NG tube”

Exactly. I was often well-enough to eat, I just didn’t eat enough or didn’t eat a wide range of food. But, it negligent to not feed anyone. I understand if it is the ER, you can’t treat and cure a patient with an ED, but they could ask them what kind of food they can eat and maybe make it comfortable for them to do so (if they want to eat alone, or with someone, or cut it up into 20 equal pieces). I think that’s a realistic approach, but I don’t know. I could be wrong. I probably wouldn’t have eaten hospital food, but, I would’ve eaten fruits and veggies. I mean, six days without food? That’s absurd!!

Patients with EDs can be difficult patients, I understand that, but it is the job of a doctor to find a way to treat them, to communicate with them, to care for them. We don’t expect teachers only to teach the model kids, right, they have to team the whole class, help those who are struggling, and even motivate those that don’t want to learn.

Still, I wouldn’t put the blame on individual doctors as much as I’d (as always, I suppose) but the blame on the system.

Happy New Year!

Tetyana

Happy New Year, we are already in it here in Australia 🙂

I think that the Marsipan guidelines are pretty good – from what I could read (dumb ED brain, sorry) but the problem is, how many medicos will have read that?

My treatment team has now drawn up emergency guidelines for anywhere I might present to so that whoever is treating/admitting me can make sure it goes as smoothly and safely as possible. But I find the scariest thing of all was in the initial stages of many of my admissions in the ED unit itself. I would be placed straight on an ‘admitting food plan’ no matter that they had years of history of my eating and the problems I’d faced – straight back to square one. I would go usually two weeks, often more, each admission pretty much deteriorating vastly due to inability to eat what they put me on, then the ‘stepping up’ of that plan making me MORE scared and struggle more, until they finally placed me on feeds/restraints etc. I never understood why they couldn’t at least intervene asap when someone is markedly deteriorating.

Happy New Year! We’ve got 13 more hours of 2012 to go here in Toronto!

Exactly, few read them. I didn’t mention in my post this finding:

“Although the recent publication of guidelines for medical care of eating disorders by the Academy for Eating Disorders (AED) is encouraging, a survey of primary care physicians found that only 3.8% used published guidelines when making clinical decisions about patients with eating disorders (Currin et al., 2007).”

Not even one in 20 physicians use published guidelines in making clinical decisions about patients with EDs according to this survey. In some places, of course, the number might be much higher and in others, much lower, it is just a survey, but still: what in the world… 3.8%?!

That’s something Powers and Clark mentioned, “Some of the reasons medical providers rarely use practice guidelines for eating disorders are that existing guidelines tend to be lengthy, focused on the psychosocial aspects of treatment, and developed mainly by experts in eating disorders.”

So, we need shorter guidelines and frankly, I think a lot of this needs to be taught during medical school and residency.

My boyfriend learned about a lot of very, very rare neurological diseases but he had only one vignette about eating disorders in his first year of medical school (as far as I remember, if I’m wrong, I’ll update). I don’t mean that med school students (or nursing students, or any other healthcare professionals) need to be taught about the ins-and-out of eating disorder diagnosis and treatment, but I feel that without any training or very limited training, what we end up getting are physicians who have the exact same misconceptions about eating disorders are the general public. That’s unacceptable.

As your experience highlights, another huge problem I think with ED treatment is complete disregard for the patient’s desires, wishes, and even medical history sometimes. I think a lot of medical care infantilizes eating disorder patients: suddenly you have no say in your care, at all. I think you should have some say, anyway, especially when you know what they are doing is only making things worse.

Ugh, I’m so sorry to hear that you want through that. It makes me so angry.

Tetyana

Hi 🙂 I’m glad my comment made it through, I thought I forgot to fll out the form – thought that it would have disappeared.

3.8%??? I don’t even know what to say. That is astounding.

Totally agree with your comment about being infantilised and our desires not being regarded. What makes my situation (I think) worse is that I was a repeat patient, we are talking about the same consultants, often the same registrars, and mostly the same nursing staff, dieticians etc, as had been treating me continually for YEARS – no matter what had ended up ‘helping’ me the last time around, they would revert back to ‘protocol’ each new admission as though I had NEVER been there before. Even if the subsequent admission was only a few weeks or even less than a week later – no, back to the same plan each first time admitted patient would be started off on.

If it was for refeeding purposes I can understand that, but the ‘admitting’ meal plan at our unit is pretty much a basic normal hospital diet – which is probably not very safe to give any anorexia patient or patient at risk of refeeding syndrome in their first days of admission!

Gah. So many frustrations 🙁 Often I feel like i’ve been their guinea pig over the years, I can see so many ways in which they have (finally) made huge improvements but in so many ways, I feel like I went through an extra little bit of hell for them to finally realise “Oh this didn’t work”. And if WE tell them it’s not helping us, the stock standard answer is “Of COURSE you are going to not like this – you are an ED patient and you will never like what we do for you, you will always look for some excuse to reject treatment’ 🙁

Oh well. Looking to the future and more awareness and understanding. Happy new year again, weird to be posting from the future haha 🙂

Dr Powers et al. Extremely well thought out list of treatment interfering issues. The best I have ever seen. Thank you for that

I was hospitalized for two days after having an electrolyte imbalance caused by my bulimia. The doctors had me on a potassium IV and forced me to drink a potassium supplement. During those two days, they encouraged me to order meals to my room, but I refused (knowing full well that I couldn’t purge with my electrolytes as bad as they were). They didn’t press the issue or really even try to get me to eat. I was in hospital from 2am Sunday morning until 6pm monday night without food. Doesn’t sound like very long, but for someone with an eating disorder, it wasn’t the best situation. I’m definitely not blaming them, as it was my choice, but at the same time, you would think they would know how to handle the situation a little bit better.

Thanks for your comment, Andrea.

I agree: they should know better. Yes and no on blaming them. I mean, it is a difficult situation to be in for you and for the doctors, no doubt, but having a patient with an eating disorder who denies food is not a good reason to not give them food or to not find a workable solution to at least get some nutrients in.

In your perspective, now, what would be the ideal way for them to have handled the situation, do you think?

Thanks for the post! Did either of the stories result in a lawsuit? I am trying to locate a case for a grad school project. Any leads would be appreciated!