Refeeding syndrome (RS) is a rare but potentially fatal condition that can occur during refeeding of severely malnourished individuals (such as anorexia nervosa patients). After prolonged starvation, the body begins to use fat and protein to produce energy because there are not enough carbohydrates. Upon refeeding, there’s a surge of insulin (because of the ingested carbohydrates) and a sudden shift from fat to carbohydrate metabolism. This sudden shift can lead to a whole set of problems that characterize the refeeding syndrome.

For example, one of the key features of RS is hypophosphotemia: abnormally low levels of phosphate in the blood. This occurs primarily because the insulin surge during food ingestion leads to a cellular uptake of phosphate. Phosphate is a very important molecule and its dysregulation affects almost every system in the body and can lead to “rhabdomyolysis, leucocyte dysfunction, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, hypotension, arrhythmias, seizures, coma, and sudden death.”

I’m not, however, going to go into too much detail on RS as there are pretty good sources available here, here, and here. Instead, I want to discuss some practical guidelines that have been recently proposed on how to avoid RS. These new suggestions have come about as a result of recent publications suggesting that current and commonly used refeeding guidelines might actually do more harm.

These new guidelines take into account clinical findings and pathophysiology of RS. Yay for evidence-based treatment!

What are the current clinical guidelines?

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends a gradual increase in calorie intake, regular physical monitoring and adjunctive oral supplements (such as phosphate). NICE guidelines also recommend a weekly weight gain of 0.5-1kg. The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, as well as the American Psychiatric Association echo these guidelines.

In all of these guidelines, initial caloric intake is below daily requirements, with slow increases recommended. It is important to emphasize that there is no evidence-based research behind recommendations in the current refeeding guidelines, which range from an initial rate of 10 to 60 kcal/kg per day.

(Just a note: 1 kcal = 1000 calories, but when we talk about food calories, we are actually talking about kilocalories or capital “C” calories, so 60 kcal/kg per day is the same as 60 calories/kg per day in normal speak. See this handy Wikipedia entry. Thanks Alison for pointing this out!)

In a short review of published studies on the occurrence of RS in anorexia nervosa patients, O’Connor and Goldin found that in all of the cases, the patients were following the currently published guidelines. “The refeeding syndrome presented itself with hypophophataemia, hypotension, and cardiac abnormalities while refeeding at an average rate of 27 kcal/kg per day.”

O’Connor and Goldin found that regardless of whether refeeding starts with 10 kcal/kg a day or 60 kcal/kg a day, there still seems to be a high risk of refeeding. So, simply starting low and increasing caloric intake doesn’t seem to prevent RS.

How can the current guidelines be improved?

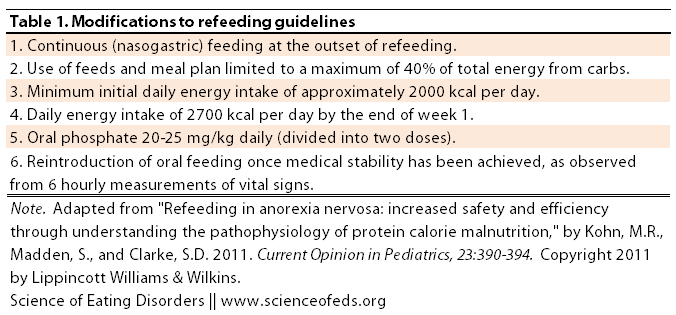

Kohn et al. suggest the following modifications to the current guidelines:

So why these recommendations?

Let’s go in order.

Number 1. A previous study by Gniuli (2001) found delayed insulin release and resulting hypoglycemia after ingesting a test meal in anorexia nervosa patients compared to controls.

“These metabolic alterations may represent a way to preserve calories by enhancing energy storage; however, they potentiate the risk of developing recurrent hypoglycemia [low blood sugar] with intermittent oral feeding, and are more pronounced with calories in the form of carbohydrate, as compared with protein or fat.”

Using nasogastric feeding–which results in a constant supply of calories–can help avoid low blood sugar levels which result from the delayed insulin response to food intake in AN patients.

Number 2. Limiting carbohydrate intake can help reduce the insulin surge that can lead to RS. O’Connor and Golding write that reducing the calories coming from carbohydrates (ie, glucose) would limit the “shift in fluid and electrolytes and therefore possibly avert the refeeding syndrome.”

Number 3 & 4. The rationale for the relatively high initial daily energy intake (50 kcal/kg for a patient of 40kg, for example) is to avoid the the weight loss that occurs during the initial stages of refeeding (because the initial recommendations are still well below the daily metabolic requirements of the patients). Moreover, the authors report using these calorie guidelines in refeeding patients with good outcomes and no episodes of RS (Kohn & Madden, 2007; Whitelaw et al., 2010).

Number 5. Phosphate supplementation is crucial to avoid low phosphate levels. These recommendations are not new, but they are more specific (in terms of the actual amount to supplement) based on the authors’ clinical experience. Though, of course, the supplementation amount will vary from patient to patient and phosphate (and other electrolyte levels) must be measured regularly.

Number 6. This one is pretty straight forward: reintroduction of normal eating and the removal of the nasogastric tube.

So there you have it: a move toward evidence-based treatment guidelines, isn’t that great? I hope that the integration of these guidelines into mainstream medical practice prevents adverse outcomes and saves lives.

The authors conclude by summarizing their recommendations:

These studies highlight the importance of the maintenance of blood glucose and phosphate levels, and provision of adequate calories at the outset of refeeding, to establish early weight gain. The avoidance of low blood sugar from the effects of delayed insulin phase and metabolic changes with regard to glycogen storage and fatty oxidation support the use of continuous feeding strategies, such as nasogastric tube feeding at the outset of refeeding as well as limiting the proportion of daily calories from carbohydrates to less than 40%. Oral phosphate supplementation should be routine and blood phosphate levels should be maintained above 1.0 mg/dl.

References

O’Connor G, & Goldin J (2011). The refeeding syndrome and glucose load. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44 (2), 182-5 PMID: 20127933

Kohn, M., Madden, S., & Clarke, S. (2011). Refeeding in anorexia nervosa Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 23 (4), 390-394 DOI: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283487591

I’m always a fan of investigating (appropriately) anything of scientific interest. And I think it’s important to investigate different rates of re-feeding and the risks/benefits of each.

One thing I am NOT a fan of, however, is that these studies often ignore the potential psychological risk to the ‘research subjects’ that come as a result of refeeding- particularly when the calories and rate of weight gain are on the high end of the spectrum.

Again, I’m not saying we shouldn’t be studying this. But I haven’t seen any serious efforts to: 1. Tie these “nobody-died-so-these-feeding-rates-must-work” results to the eventual outcome of recovery (i.e. how does the weight of initial weight gain affect relapse rates and/or severity?), and 2. mitigate the *other* major risk factor for fatalities in low-weight patients: Suicide. Studies have shown in the past that treatment drop-out is high in programs that focus almost exclusively on weight restoration. We need to *ALSO* consider what’s happening to the psychological well-being of these patients when they’re being fattened up as fast as medically possible. And, to be fair, it may actually end up that people who gain weight super-fast actually do *better* psychologically. But we don’t yet KNOW that. So I wish there was more attention paid to this risk by those conducting these studies.

Yeah, I agree with you.

But I think the issue here is avoiding refeeding syndrome in the initial stages of refeeding and limiting the weight loss that typically happens when clinicians “start slow” because the caloric intake is still below the basal metabolic needs of the patient. To me, these studies aren’t looking at long-term rate of weight gain or thinking about weight-gain as the only treatment component. Instead, they are just focused on avoiding RS in the first few days/weeks of refeeding–they have nothing to say about the treatment program at large. It is just medical doctors/physiologists concerned about the medical safety of the patient.

I actually thought there were some studies that suggested a higher rate of weight gain was predictive of better outcomes?

And Joy, eating 2000 kcal/day isn’t going to lead to a super-fast weight gain, it will just prevent further weight loss initially.

The authors mentioned a few times that following this protocol seemed to have positive outcomes on the patients, as well.

For example, with regard to the NG tube: “The patient experience of nasogastric tube feeding has been recently reported by Halse et al. [26]. Consistent with other studies commenting on the experience of nasogastric tube feeding, no difficulties were experienced in re-establishing a diet with regular food, patients and families tolerated this treatment approach, and no psychological trauma was described in qualitative assessments of patients receiving this form of treatment.”

Actually, being ‘fattened up’ plays a big part in doing better psychologically. When you are starved, you can’t think straight. Anxiety, depression, obsession with food, ect, is made worse with starvation. (Like in the Minnesota starvation experiment). In order to make progress with therapy, your brain has to function, and it doesn’t if you are still losing weight.

Obviously, this is only my own experience, and I’ve never been inpatient (though I’ve talked to others who feel the same way) so it doesn’t prove anything.

But I found that I had two ‘voices’ in my mind, one that was ‘me’ and wanted recovery, and the ED.

When a doctor listened to my ED voice and let me only gain 1kg in a month, it was… harder. Neither side of me was happy with this, and I was even more torn. When you have been so focused on only losing weight for so long, it’s confusing to be told to ‘Gain weight, but not too much. Eat more, but don’t overdo it. You have to restore your weight to be healthy, but we will only make you go up to the minimum safe amount.”

The eating disorder latches on to this. In my case, whether I’m eating 1500 or 2500, gaining 1 or 3kg, I feel horrible. I’d rather get over it as fast as possible (of course, it would be practically impossible to get anyone in the middle of an ED to admit to this!).

actually, Kohn and Madden have asked the kids how they feel about NG, and the weight, and looked at outcome data.

Glad to see this is being talked about more publicly, as it is an issue, I’ve found few people are aware of. It’s important that it become more well known for families, or people with eating disorders that are trying to improve on there own, will know of very necessary precautions. Personal experience has shown me that not many doctors (at least that I’ve worked with) are well educated on this matter, which made my life a lot more difficult, but can also risk someone’s life. Hopefully articles like this can help bring the issue to light, preventing further harm

Yeah, I agree with you. I’m particularly worried about patients trying to recover on their own (or without professional help, anyway). There are a lot of questions about what foods to eat and how much during early stages of refeeding, so I hope this info helps those who don’t have access to good medical help or are stuck with doctors who are not well educated on the topic (or following old guidelines that aren’t optimal for avoiding RS).

Happy to help! 🙂

And this was good to read. When I first started seeing my nutritionist, she was concerned about RS with me, though thankfully I seem to have avoided it. The main thing she had me do, which was new to me and helped a LOT, was the limiting of carbs and increasing of protein. This wasn’t super easy as I’m a vegetarian, but I found ways to do it and dang, did it help me feel better. I had severe gastric discomfort all the time before that, but after, it got much better.

I’m glad they’re working out better ways to approach RS though, because it sounds scary. When I first heard about it I was honestly almost afraid to even try recovering because of it, which is sort of silly, but…better the devil you know, I guess.

I’m glad that she had you do that (limit carbs and increase protein!).

It is scary but it is DEFINITELY avoidable, the key thing is really to monitor the patient regularly.

Where there specific foods you found really helped limit the gastric discomfort?

Hmm…well, I found when I switched to protein-rich nutrition bars as opposed to regular granola bars, that was a big help. Also, and I know some folks have their issues with soy, but soy-based products seemed much easier on me – veggie burgers for example. Also started eating nuts daily. But again, I think it was mostly just the “more protein” thing that helped, because before that change I was probably barely getting any.

RS can be a really serious issue. It happened to me the last time I was in IP treatment and I had to be transferred to the medical hospital as a result. And in the IP admission before that one, in another facility, we were started off with a liquid diet, but calories were so low… 900 and 1200 calories to start with. They were supposed to be monitoring my wonky electrolytes, but lost my labs somehow, and I ended up losing weight on their diet, so I just left the programme… I’m anorexic, I can lose weight on my own, you know?

In my country, ED research isn’t the most advanced (a lot of emphasis is put on psychotherapy and psychoanalysis, instead of biological, genetic, epigenetic, brain structure abnormalities, not to mention behaviours being driven by actual malnutrition), so with certain aspects of recovery practitioners are often not well-versed – especially with the medical and scientific matters. I even know one woman here whose daughter died whilst IP in one of our major hospitals here, because she was not being medically monitored for RS.

The next time I have to go IP (which I really do want, in order to get intial structure and support during refeeding that is hard to get at home), I will go to a nearby country that is larger and a bit more current when it comes to medical monitoring and the latest scientific research.

I’m so sorry to hear about your terrible experiences and about the death :(. It is so terrible when these things are easily avoidable with knowledge and proper medical monitoring, you know?

The initial weight loss isn’t surprising given the low caloric intake they started you with. This is why Kohn et al suggest starting with at least 2000 but using an NG tube and low carbs to avoid RS and insulin surges.

I hope IP in another country if possible–will be more fruitful. I agree that the structured nature of these programs is really crucial, particularly in the early stages, and to make sure that any medical emergencies can be dealt with immediately.

Tetyana

This is a great resource! I don’t have any experience with refeeding syndrome, but I’ll definitely redirect people to this post who want/need to know more about preventing the condition.

🙂 Thanks!

Interesting and a well written article.

I’ve briefly looked both of those articles in the past. I’ve just though had a quick look at the other authors Khon et al 2007 article and i’ll quote from it.

“In the last 10 years, over 400 adolescents, with mean age 13.8 years and mean body mass index 14.1 kg/m2, have been admitted to the Adolescent Eating Disorder Service at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead for refeeding to treat PEM associated with AN.

Adolscents with AN with a mean BMI of 14. On admission in excess of 80% of patients have not been medically stable (i.e. pulse <40/min, temperature <35.5C, or systolic blood pressure <70 mmHg). Refeeding syndrome, as recognised by the occurrence of delirium, has been diagnosed in two of these patients. There have been no significant cardiac events recorded, nor have any patients required supplementation with other than a standard multivitamin preparation and phosphate. Replacement fluid and nutrition have been supplied by oral feeding and/or nasogastric tube. Calories from carbohydrates constitute less than half the total energy, with 30–40% of calories being derived from fat. Weight gain has averaged 0.75 kg each week for this cohort of patients, who are graded up to receive 3000 kcal daily."

……………………………

These group of young adolescents with a mean BMI of 14.1 at 40kg this may equal a 50kcal refeeding rate at 2000kcal. Another group in inpatient with a mean BMI of 10 or 11 this initial 2000kcal figure will put their refeeding rate above the current recommended 10kcal-60kcal. This would put the kcal rate at about 75kcal which appears to be way above 75% of TEI. I think it is better to focus more on the kcal. A lower weight <30 IBW also increases the risk of RS. Some people will demand a more specialised refeeding approach.

"Prognosis in 41 severely malnourished anorexia nervosa patients"

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22459953

"Specialized refeeding treatment for anorexia nervosa patients suffering from extreme undernutrition".

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20416994

The group though of severely emaciated patients with a long history may for example be more likely to develop cardiac issues during the refeeding process so going slower may be more appropriate. Other complications due to longstanding AN might possibly complicate/prolong the initial refeeding process also.

For many adolescents though a more aggressive program like this may be useful given such the short window there there is <3 years before things are meant to get harder to get right. This approach though may not be appropriate for all adolescents or all adults.

But, i agree though that it's good that more research has been conducted into carbohydrate ratios.

Even still though when talking about standard practice, those higher rates is higher than what is being used in a lot of units at least in the UK anyway, it's challenging to the status quo, but not going to deny it, my response to this personally i guess would be typical, so i'm not going to go there lol.

When i wrote it is better to focus on kcal, i meant rather than going by a specific calorie amounts.

The ratio of carbohydrate, protein and fat is important and at lower kcal rates to is very important. Some people still though due to their needs may demand different amounts of each group.

I should add as well that metabolic rates will still vary among different people in all BMI groups. May be some professionals will be more responsive to this. The current kcal being consumed pre ip is sometimes taken into account also.

“I should add as well that metabolic rates will still vary among different people in all BMI groups. May be some professionals will be more responsive to this. The current kcal being consumed pre ip is sometimes taken into account also.” Definitely, I especially agree with the latter point.

missr, I’m a bit confused, to be honest.

“even still though when talking about standard practice, those higher rates is higher than what is being used in a lot of units at least in the UK anyway, it’s challenging to the status quo, but not going to deny it, my response to this personally i guess would be typical, so i’m not going to go there lol.”

What do you mean?

I just mean that 50kcal refeeding rates or at least 2,000 calories does not seem to be the norm yet to start most people of on it seems at least where i live. This new research on the refeeding rates/carbohydrate ratios challenges what has been accepted as standard practice by many.

The second part really wasn’t intended to be taken seriously at all and I just basically meant that someone might complain about the higher rates etc.

Why aren’t doctors better educated about this?

I had a very sudden onset of AN, at age 15, and only severely restricted for a couple of months. By the time my mother dragged me to the pediatrician, I’d been eating < 1000 calories for weeks but had stepped up my intake in the last few days because of parental pressure (and fear of parental interference). The doctor didn't know what to do with me except give me a lecture, order bloodwork, and send me home. It turned out I had borderline hypophosphotemia. Well, the doctor didn't know what to do with that either, and I never got phosphate supplements or monitoring for refeeding syndrome, even after I started seeing an ED-specialist team. In hindsight, this is terrifying to me.

E, that is very terrifying.

“Why aren’t doctors better educated about this?”

That’s a complex question, and I think the answer is multifaceted. Priorities, stigma, lack of awareness of the issue. I don’t know.

I’m wondering how long refeeding syndrome can last? I ask because I know I gained 30 pounds of water in the first few weeks of recovery and continued to gain at 10 pound intervals for weeks after. I have continued to gain, despite being in recovery for over a year, and being very far above my set point. I have never released the water retention, so am probably carrying around 50 pounds of water if not more. I’ve had blood work done, with nothing really standing out, but with no doctors that really seem to understand eating disorders and recovery, getting answers has been incredibly hard. I was finally able to talk to someone somewhat knowledgeable about recovery, and she mentioned to me that she wondered if I had had refeeding syndrome and that it lead to something else. But, I have no idea what that would be. Very frustrating when doctors do not help at all and accuse me of overeating my way into drastic weight gain, which is not at all true.

I read your comment and can relate to everything you’ve experienced. I too am about a year into recovery but am holding onto a good deal of the water and am well over my normal set point, as a result of the fluid retention. Blood/physical tests are all normal. I’m also running into dead ends when I try to get answers to the chronic edema and digestive issues. One doctor mistook the edema for actual weight assuming that I’m overeating or something, which is frustrating because I’ve stuck to a very healthy diet of 2500-3000 calories since starting recovery.

I can only hope we get some answers KO. Every doctor I have been to has mistaken my edema for weight and have accused me of binge eating. One even suggested I attend Over Eaters Anonymous! Great for a recovering anorexic! Of course I continue to worry that something else is wrong with me, but with no one willing to take me seriously, I continue to trudge forward, hoping to one day wake up and not look like the stay-puff marshmallow man. Recovery is baffling sometimes.

Two things have really helped to drastically reduce the edema for me recently (over the past few weeks). I didn’t believe they would help when my doc recommended them but they did. I basically reduced my intake of simple carbs while increasing my intake of proteins and healthy fats. I also take a high quality probiotic, which seems to help with digestion. I think the reduction in simple carbs is what really did the trick for me in terms of water reduction, however. I replaced simple sugars/carbs (like juices, pastas and sweets) with proteins and healthy fats (like turkey, chicken and olive oils). I basically choose meats, cheeses, etc over pasta dishes, breads, etc. Continue eating complex carbs like vegetables, fruits and whole grains. I’ve been struggling with the blasted edema for well over a year and this simple diet change has helped me immeasurably. Nothing else worked prior to this and I’ve tried just about everything. I was struggling to finish meals and often suffered with severe abdominal distention and bloating after every meal. Now I am finally regaining my appetite and eating without much stomach upset. The water swelling has reduced by at least 75%. Give yourself a week or two before you’ll notice swelling reduction. Hope you’re feeling better soon

One more thing: if you’re not too savvy with nutritional info like me, then just pay attention to the sugar content of your foods (something with 30grams sugar would be high whereas 2grams would be low). Try to stick with foods that have low total sugars, similar to diabetic diets. I’ve found that I can eat/drink pretty much anything that I’d like as long as it’s not too sweet (which often correlates with high sugar/carb content). It seems that carb loading/sugars are responsible for much of the bloating and overshoot weight gain that occurs for some patients during recovery. You won’t hear MDs talks about this, however, because most know nothing at all about nutrition, particularly as it applies to recovering anorexics. Sorry if I rambled on. Best of luck to you