What is different about anorexia nervosa sufferers that, in contrast to most dieters, enables them to maintain a persistent calorie deficit? Although no one can truthfully claim they know the full answer to that question, we do know that part of the answer most likely lies with serotonin (5-HT), a molecule that neurons use to communicate with each other.

I’ve written about serotonin in the context of anorexia nervosa before, so I’ll just do a brief summary of the important points here:

- Serotonin has a lot of functions in the body; it plays a role in regulating appetite (satiety), sleep, mood, behaviour, learning and memory, and a variety of other things

- Serotonin has been implicated in obsessionality, harm avoidance, and behavioural inhibition

- Alterations in serotonin function have been linked to many disorders, including depression, OCD, anxiety, and eating disorders

- Serotonin is made from tryptophan, an essential amino acid (meaning that our bodies cannot synthesize it and we must get it from our diet)

Given that serotonin mediates a lot of psychological and physiological traits associated with anorexia nervosa, and given that altering food intake affects how much serotonin is made in our bodies, it is no surprise that it has been a popular research target among eating disorder researchers.

Two important findings that are particularly relevant to the study I will discuss below are:

- Underweight AN individuals have reduced concentrations of 5-HT (actually, reduced concentrations of a metabolite of 5-HT, 5-HIAA, measured in the cerebral spinal fluid), suggesting there’s a reduction of 5-HT activity during the ill state

- Weight-restored AN individuals have increased concentrations of 5-HT (again, deduced from the reduction of serotonin’s metabolite, 5-HIAA)

These findings suggest that individuals with AN may have premorbid (or intrinsic) abnormalities in the serotonergic system (elevated 5-HT activity compared to healthy controls), which may mediate behavioural and/or temperamental traits that in turn predispose these individuals to develop AN (perhaps as a means of reducing, and in turn “normalizing”, their serotonin activity by modulating their dietary intake of tryptophan).

This raises the question: What are the psychological effects of reducing serotonin in anorexia nervosa sufferers?

Luckily, researchers can address this questions experimentally using a procedure called acute tryptophan depletion (ATD). ATD reduces plasma tryptophan and thus decreases serotonin synthesis, release, and neurotransmission.

In 2003, Walter Kaye and colleagues published a study that examined the effects of reducing serotonin neurotransmission through ATD decreased anxiety in individuals with anorexia nervosa. Using a randomized double-blinded study design, they evaluated the effects of ATD in ill (ILL AN), weight-restored (REC AN), and healthy control women (CW).

They hypothesized that “people with AN have a trait-related increase in 5-HT neuronal transmission that occurs in the premorbid state and persists after recovery. Increased 5-HT neurotransmission in turn contributes to uncomfortable core symptoms such as obsessionality, perfectionism, harm avoidance, and anxiety. […] [And] that people with AN starve themselves to reduce 5-HT neuronal activity and thus reduce a dysphoric behavioral state.

The participants reported their levels of anxiety, depression, and irritability prior to the experiment and hourly (for 6 hours) following ATD.

MAIN RESULTS

- Baseline tryptophan levels were highest in the REC AN group and were significantly different from the ILL AN and CW groups; there were no differences between the ILL AN and CW groups

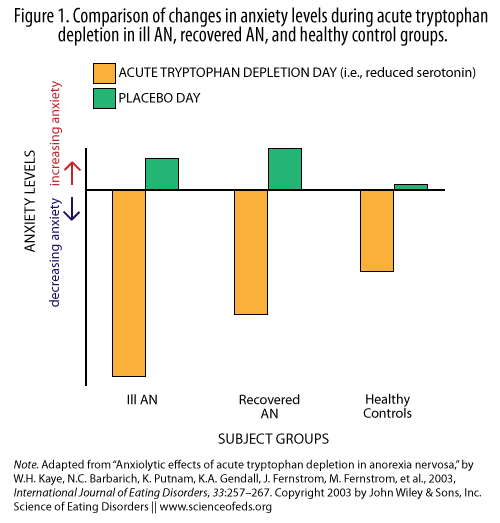

- Following ATD ILL AN and REC AN groups experienced a significant reduction in anxiety (the CW group had a trend toward a difference); see Figure 1 below

- There was a relationship between the reduction of tryptophan and levels of anxiety in the ILL AN group but not in the REC AN or CW groups

- There were no differences in depression or irritability ratings between the ATD versus control day within each group and between groups

WHAT DO THESE RESULTS MEAN?

Essentially, the findings support the idea that caloric restriction may act to reduce anxious states in AN patients. At the very least, dietary-induced reduction of tryptophan, a precursor to serotonin, seems to be associated with a decrease in anxiety in individuals with AN.

The finding that weight-restored AN participants had significantly higher tryptophan levels than both the ill AN and healthy control groups further supports the notion that individuals with AN have alterations in serotonin function. These alterations may contribute to traits commonly associated with AN such as “obsessionality, perfectionism, harm avoidance, and anxiety,” and in turn, predispose these individuals to anorexia nervosa.

We hypothesize that people with AN may discover that reduced dietary intake, by effects on plasma TRP, is a means by which they can crudely reduce brain 5-HT functional activity and anxious mood.

Many people attribute restriction in AN to a strong desire to be thin or a fear of becoming fat, and while this certainly has some validity (perhaps more for some and less for others), I do fear that it sometimes ignores the physiological effects that restriction can and does have on mood and anxiety in AN sufferers. I think part of the reason that the sociocultural explanation is so popular is that it is a socially acceptable explanation that makes sense to a lot of sufferers, parents, and peers.

When I first became ill with anorexia nervosa, I distinctly remember how calm restricting made me feel. Of course I had no idea that restricting altered levels of serotonin in my brain; I didn’t know anything about serotonin or neurotransmitters. To me, the explanation that I was restricting my intake because I wanted to lose weight, regardless of how silly people thought it was (none of my friends dieted) at least made some sense. Dieting is fairly common, a lot of people want to lose weight, so on and so forth. Maybe my friends thought I was vain and shallow, but at least that made more sense that the ridiculously-sounding (at that age, I feel) notion that not eating is calming.

Of course, that’s not necessarily the case for everyone with AN and I certainly do not want to discount the role of the media and the thin-ideal. However, I do feel that the ubiquity of dieting probably acts to expose a lot more people — people who would otherwise never stumble upon this — to the fact that by restricting their intake they can regulate their anxiety levels.

A WORD OF CAUTION

As interesting as the findings in this study are, it is important to remember that ATD is an indirect way to alter levels of serotonin in the brain and from what I’ve read, it is not entirely clear to what extent this procedure reflects or modulates levels of serotonin transmission in the brain. There seems to be some controversy over whether researchers are actually measuring what they think they are measuring (see van der Plasse, 2013; van Dunkelaar et al., 2011). Moreover, there seems to be some controversy over the effects of ATD on anxiety levels in individuals with anxiety disorders and OCD, as well as the effects of ATD in healthy women.

In addition, this was a small study: there were only 14-15 individuals in each group, so it is unclear how generalisable these findings are to the larger population. Furthermore, the ILL and REC AN groups had a mixture of AN subtypes, which may have altered the results as well.

It is also important to remember that brain neurotransmitter systems do not act in isolation. Altering serotonin neurotransmission alters other systems as well. So it is difficult, if not impossible, to pin particular behaviours or states to a single neurotransmitter system.

FINAL THOUGHTS FROM THE AUTHORS

The 5-HT neuronal systems in women with AN may not be able to sufficiently compensate and ‘‘buffer’’ the ATD-induced changes in 5-HT release. It is possible that people with an inherent modulatory defect in 5-HT function may be prone to developing an eating disorder, because they cannot respond appropriately and precisely to stress or stimuli or modulate their affective states. People with AN may discover that restricted eating, by its effects on availability of plasma TRP, is a means by which they can crudely reduce extracellular 5-HT concentrations, and thus briefly reduce a dysphoric state.

EDIT: I didn’t think this would need to be said but just in case you are new to reading the Science of Eating Disorders blog or are otherwise confused by the title: I am not promoting restricting or anorexia nervosa. My goal is to explain one possible neurobiological explanation for why individuals with higher levels of central serotonin neurotransmission may be predisposed to develop anorexia nervosa. Understanding the physiological effects of restricting in individuals with anorexia nervosa, I believe, can be a powerful tool to understand not only what factors may contribute to causing and maintaining the eating disorder, but also to why recovery is so hard.

References

Kaye WH, Barbarich NC, Putnam K, Gendall KA, Fernstrom J, Fernstrom M, McConaha CW, & Kishore A (2003). Anxiolytic effects of acute tryptophan depletion in anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33 (3) PMID: 12655621

As a longstanding sufferer of restricting AN, I can very much identify with this hypothesis. Energy deprivation and weight loss indeed alleviate my high levels of (constitutional) anxiety.

In fact, restricting food seems to calm a variety of neurological functions. One of the things I found really difficult when I gained weight from an emaciated state was that my ability to focus and to concentrate lessened. Bizarrely, I had written my PhD thesis and some of my best published papers when I was restricting massively and was very underweight. But my mind was ‘all over the place’ when my nutritional status improved. I was as anxious as hell and had the attention span of a gnat…

As you point out, this study doesn’t wholly ‘prove’ the hypothesis that restriction is anxiolytic, but it’s a hypothesis that makes sense, to me at least.

Thanks, Tetyana!

As you say, it doesn’t prove the serotonin hypothesis, and as I dig deeper, it does seem like there are more holes. I am not sure to what extent ATD is established as a valid tool for assessing central serotonin neurotransmission. And, of course, there are studies that seem to counter the effects of ATD hypothesized in this paper. But anyway, it is interesting.

I found that my concentration levels definitely improved with weight-restoration but at the same time, I became a lot less focused and driven with regard to my marks, for example. But that was a good thing: My life became much more balanced.

It is murky waters. I like this hypothesis as well, and do identify with it, but we’ll see.

Also, you are back to blogging! Good news! Hope all is well.

Though the study did not prove the hypothesis, I find this form of research is crucial to both understanding and treating eating disorders. What people need to understand is that for many people there are “perks” to various behaviours. One of my greatest triggers for relapse are high levels of anxiety as I do find that restricting eases them. By accepting and proving that eating disorders are coping skills, albeit unhealthy ones and this makes them so much harder to treat.

Thank you for researching these things. I’ve only just recently realised I may suffer from AN, as I use restriction to lessen the intense anxiety I face every day. I have never been able to eat when anxious and have been like this for as long as I remember, and possibly from birth. But I fell under the radar as its never been about wanting to be thin or being afraid of being fat. I’ve always longed for curves! Defective neurotransmitter modules seems a much more plausible explanation for my non fat-phobic AN.

how long of a state of starvation would it take to get to this level?

Lauren, what do you mean by “this level”? Level of what? I’m a little bit confused as to what specifically you are referring to.

This is a fascinating post because I can also identify with the idea that restricting calorie intake reduces anxiety. I came to this realization myself during a period of restriction. One day, as I walked to work, I thought, “Wow! I am so much calmer and less stressed out at work now that I’m eating less again.” To me, it seems like eating can have a very temporary stress-relieving effect, but not eating relieves my anxiety over longer time periods.

I wonder whether the increased seratonin levels in recovered AN patients are due to the after-effects of their disorder, rather than being indicative of their having had a high-seratonin level before restricting began. What I would love to see are prospective studies where seratonin levels are measured in adolescents, who are then followed to see who develops mental health issues. Or, perhaps compare the findings of this study to the effects of calorie-restriction on anxiety in healthy volunteers, similar to the Minnesota starvation experiment with Ancel Keys. I remember reading the book The Great Starvation Experiment (2006) and the authors said they remembered feeling edgy.

Also, I would be interested to find out how restricting could be used not just as a way to self-regulate anxiety, but also libido, as restriction definitely has been shown to cause changes in sexual function.

I’ve come to realize that I am absolutely self-regulating my anxiety through food restriction. While not visibly underweight, I am on the lower side of the healthy range for my height-frame etc. I don’t identify as anorexic, but I definitely restrict for anxiety relief, mood stabilization, energy and endurance… If eat during the day I become so lethargic and sleepy and irritable and depressed – if I don’t eat until the end of my day, I do not experience any of those symptoms.

I am certainly not functioning optimally, so this is very interesting to me – especially as someone with a history of depression and taking scores of antidepressants and other psychotropic medications. The link with serotonin is something I will have to further read about. Look forward to exploring your other articles!

Thank you for this insightful paper and your commitment to furthering the status of anorexia as a legitimate disease with a physiological basis.

I have suffered from anxiety, perfectionism, and the full spectrum of eating disorders. However, I have always felt like I was at my happiest mentally during a restrictive period.

After recovering physically, I was put on a very low dose of a SSRI in an attempt to combat the anxiety. Two weeks later, I was in the emergency room with serotonin syndrome. I have since had two physicians say that they were amazed that such a low dose could have caused this effect. I would be extremely curious to see if there was a connection between eating disorders and the prevalence of serotonin syndrome, especially in light of this research.

Just as some others commented that they can identify with their eating disorder reducing anxiety — I can also relate to this. I have struggled with AN throughout my life. I have gone through recovery multiple times — and each time that I have relapsed has been directly due to anxiety. I definitely made the connection long ago that I seemed to feel less anxious when I was restricting — thus, when I experience triggers/surges of anxiety, I’m always at high risk for relapsing and I know this.

The entire reason I stumbled upon this article was because I was looking to see if there was actually any science between the connection I had made long ago.

Now — as I’ve been in recovery for the last four years — I definitely notice major increases in my anxiety. Little helps — meditation, exercise, etc.

My question is — is there any known EFFECTIVE strategy to keeping anxiety at bay after recovery? The so-called effective strategies have not worked for me so far…

And like Mireaux said — SSRIs and other medications have only seemed to make the problem worse for me.

I’m looking forward to hopefully MORE studies on related topics. The common misconception that the influence of media has THAT much power drives me crazy. Although it can definitely affect our body image — the media does not explain, as you mentioned in your blog, how some people can sustain restrictive eating.

My husband who tries to understand — has asked me multiple times what I gained out of restricting, and how it’s even possible for me to ignore my body’s needs so relentlessly– it’s been very hard to put into words.

There needs to be more scientific on a biological/chemical level on eating disorders — so far much of the research has been on a psychological/sociological level, and it’s just not enough.

I can vouch for the fact that eating disorders are not just purely behavioral or even emotional — even after long periods of adjusting behaviors and emotions and recovering there remains that need to find a way to reduce the anxiety.

Thanks for the post.