Over the years, I have read a number of articles describing eating disorder prevention programs. Unfortunately, many reveal limited efficacy, and some even highlight detrimental effects. Primary among concerns of those evaluating prevention programs is that even when effective, we often have limited data about the long-term effects of prevention programs. This lack of follow-up limits the ability to draw conclusions about these initiatives and is cause for pause for those interested in implementing strategies to prevent eating disorders.

Further, there is some debate about whether eating disorders are even really “preventable.” Given our understanding of the complex etiology of these disorders, “prevention” can be a loaded word. The nature of the proposed intervention will undoubtedly be heavily swayed toward whichever factor(s) the program’s designer feels is most important in “causing” or contributing to disordered eating (i.e., Is the program tailored toward media awareness? Nutrition? Body image?)

I approached a recent article by Gonzalez et al. (2012) with these reservations in mind, but optimistic about the authors’ use of a longer-term follow up design. The article details results from a long-term (30 month) follow-up qualitative study with a subset of school-aged girls who had participated in a larger-scale evaluation of an eating disorder prevention program.

The authors sought to determine whether participants perceived this media literacy-based program to be helpful and personally salient. Prior quantitative analysis (Gonzalez et al., 2011) had revealed:

- Reduced self-report disordered eating attitudes

- Reduced self-report thin-ideal internalization

Building on these encouraging results, the authors interviewed 12 girls (out of an initial sample of 254) about the program and its impact on their lives. The initial intervention study was comprised of 2 experimental conditions and one control condition at 7 schools. Four girls from each condition and approximately evenly distributed according to type of school (state or subsidized) and highest/lowest eating attitudes and thin-ideal internalization were chosen for this in-depth follow-up study.

These girls were interviewed, and the authors used thematic analysis informed by Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA; Smith & Osborn, 2004) to analyze transcripts. This methodology looks to explore ways of knowing; in other words, researchers using this technique seek to learn more about participants’ subjective experiences and how they think about these experiences.

THE PROGRAM

As I previously mentioned, any intervention program will be oriented toward a particular understanding of the factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of eating disorders. This program was designed with an adolescent population in mind, and is linked to 2 specific theoretical perspectives:

- Social cognitive model (Bandura, 1986): this theory argues that people act in a certain way based on their attitude toward the behaviour and the confidence they have in enacting the behaviour

- Media literacy perspective (Levine & Smolack, 2006): this perspective asserts that the media exerts a great deal of pressure on the degree to which individuals internalize thinness ideals and thus that it is important to question the content and framing of media imagery

The program had two main components:

- Nutrition Knowledge (NUT): designed to “correct false beliefs about nutrition” through education

- Media Literacy (ML): wherein students learn to critique aesthetic ideals

The 4-5 week program is described as interactive and participant-focused, and comprised:

- A PowerPoint multimedia display

- 3 sessions combined with 2 activities

- Tasks between sessions

The study was quasi-experimental (“quasi-experimental” as there were control groups, but these were not randomly assigned). In the initial intervention, students were assigned to ML, ML+NUT, or control group (CG) conditions.

MAIN RESULTS

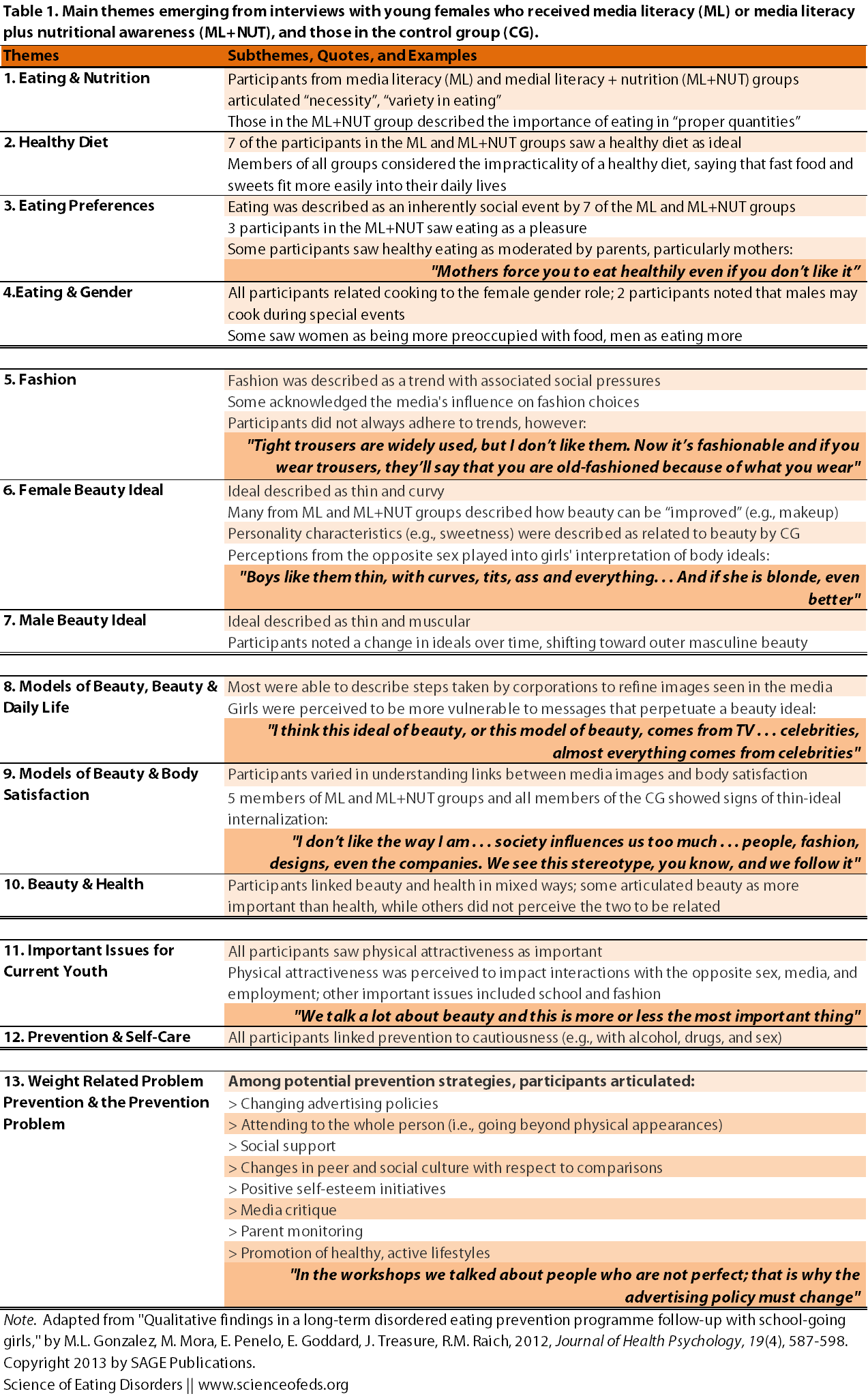

The authors found 13 major themes in the girls’ responses to questions related to food, weight, shape, media, and the prevention program:

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR PROGRAM EFFECTIVENESS?

Overall, authors note that both intervention groups (ML and ML+NUT) left the program with similar perceptions and learned similar things. However, I found that the authors understated the similarities between the control group participants and intervention participants. While the sample size is too small (only four from each group) to make a meaningful comparison in terms of thought and behaviour change, it is interesting that control group participants were able to come to similar conclusions in terms of the impact of media images on weight and shape concerns.

This article is also somewhat limited in terms of its implications for the development of eating disorders themselves. As we know, not everyone who holds negative perceptions about themselves develops an eating disorder. Further, being able to identify the unrealistic nature of media images does not necessarily mean that one becomes immune to them.

As the Gonzalez et al. (2011) article describing the quantitative findings reveals, participants in both conditions (ML and ML+NUT) had significantly lower scores on measures assessing eating attitudes (Eating Attitudes Test) and aesthetic body ideal influences. Thus, if we are using a model of eating disorder etiology that hinges on thin-ideal internalization and eating disorder attitudes, the program would appear to be relatively effective in reducing risk factors for eating disorders.

The qualitative analysis seems to be somewhat of an add-on, which, while it reveals interesting information about how young people conceptualize the mediatized world around them, does little to demonstrate the program’s efficacy. This is a rare instance in which I (as a qualitative researcher) would think that the quantitative data would tell us more useful information.

Where I do see this analysis as effective, however, is in its consideration of what young people want to see in an intervention. For this reason, the last theme, “Weight Related Problem Prevention and the Prevention Program,” is to me the most important. Half the battle of school-based problems is piquing and retaining the interest of students, so it makes sense to me to ask the students what they want to see, and then couple this information with sound theoretical knowledge of prevention programs to deliver the most effective program.

Ultimately, I remain cautious about the potential of prevention programs. Personally, I’m unsure whether there is anything that could have “prevented” my eating disorder, but maybe I’m wrong!

I’m curious as to whether any readers’ schools followed any kind of media-literacy and/or eating disorder prevention programs, and whether these seemed at all helpful? How do you feel about prevention programs?

References

González, M.L., Mora, M., Penelo, E., Goddard, E., Treasure, J., & Raich, R.M. (2012). Qualitative findings in a long-term disordered eating prevention programme follow-up with school-going girls. Journal of Health Psychology, 19 (4), 587-598 DOI: 10.1177/1359105312437433

I think you’ve summed the study up pretty well in your sentence:

“Thus, if we are using a model of eating disorder etiology that hinges on thin-ideal internalization and eating disorder attitudes, the program would appear to be relatively effective in reducing risk factors for eating disorders.”

Unlike you, Andrea, I do believe that there are some things that could have prevented my ED, but they certainly bear no relation to media, fashion, beauty, or what others desire in a woman.

I would be interested to know if any of the girls who were involved in the intervention go on to develop an ED, and if so, what they attribute the development of their ED to.

I personally find it very difficult to believe that EDs are caused by internalisation of a thin ideal. That is not to say that body dissatisfaction, or body dysmorphia play no role in the development of some people’s EDs. Concern (even disgust) around physical; appearance are common in ED sufferers, even though not everyone with an ED feels that body dissatisfaction is what drives their ED.

I, too, would be curious about the number of girls in the intervention group who go on to develop eating disorders. I wish I felt more optimistic about prevention, where eating disorder are concerned. I think that often those who design programs go for the most immediately “fixable” potential contributing factors, like thin-ideal internalization (i.e. through media literacy campaigns) because these can be broadly applied to school settings, and fit into curricula in a relatively seamless way. And while I’m certainly not saying these are not at all helpful, I do wonder whether they are really worth the clout that can accompany them. As you mention, eating disorders are certainly not always associated with thin ideal internalisation and/or body dissatisfaction. I worry that the undue focus on these factors may make some feel like the work is done in terms of prevention, when they might not be making a big, if any, difference. However, I understand that other contributing factors would be much harder to address, so as long as these programs aren’t doing any harm perhaps they are worthwhile… I might suggest the rhetoric around such programs be re-oriented, however, to be less about “eating disorder prevention” as I’m not sure they are actually doing that. Maybe they could be called “media literacy campaigns” (as some are).

I’m curious; what kinds of things do you feel might have prevented your ED?

My main concern about ‘prevention’ programmes which focus on reduction of ‘thin ideal internalisation’ is that they are not addressing EDs at all! I would suggest that they’re addressing societal-imposed attitudes on shape and weight, which is an entirely different issue.

At first glance, Becker’s Fiji studies (which I’m sure you’re aware of..) might suggest that the introduction of Western media to teens on this fairly remote island could cause EDs. However, none of the girls developed EDs… They demonstrated more concern over weight and shape – and some ‘experimented’ with ED behaviours, but those behaviours didn’t stick (as far as I am aware).

So thin ideal internalisation may lead to ‘copycat behaviours’ and even aspects of disordered eating, but this is completely different to getting stuck in a pattern of behaviours that are driven by intrusive thoughts, as occurs in an ED – alongside the awful mood disturbance.

You ask what I feel could have prevented my own ED…

OK, well my ED was an extension of childhood OCD and was triggered by anxiety and depression – along with traumatic experiences that my parents were unaware of (because I didn’t tell them). So what could have helped was:

1. Recognition and treatment of my childhood OCD.

2. Recognition and treatment of the depression that pre-dated the onset of my ED by approx. 1 year.

3. Not being traumatised! Or, at least having had help managing that trauma and the accompanying PTSD.

I almost laugh at the irony of the issues relating to ‘beauty’ addressed in this study from my own experiences. The very LAST thing I wanted as a teen was to look sexually attractive and pretty – and I was terrified of boys and men.

Good point, and great example with the Fiji studies; I’ve found that people tend to misinterpret this work to mean “Western culture leads to more eating disorders!” without looking more deeply into the study’s actual conclusions about the interplay between socio-contextual factors (and “Western society”) and eating disorders, which is, as we’ve learned, far from causal.

Thanks for answering my question about your own experience. I think that the “recognition and treatment” aspect is absolutely key. Perhaps a better focus of time and energy for “prevention” might be around education about eating disorders and the various comorbidities that are associated with eating disorders (i.e. OCD, depression, etc.) and on recognition and early intervention for these.

Your last point is interesting, too- I think it is odd how assumptions are made about individuals with eating disorders wanting to be attractive to others, because I’m skeptical about how often this is actually the case. A decent amount of literature points to the potential for eating disorders to be more about erasing (rather than enhancing) the physical self (i.e. more about invisibility than visibility). So it is curious to me that the focus becomes “physical attractiveness.” While aiming for “body ideals” might be the impetus that starts a spiral toward an eating disorder for some individuals, it is most certainly not a universal chain of events.

I don’t want to devalue the experiences of those who DO find the pursuit of a thin ideal to be an inciting factor in their eating disorder (nor do I think you are doing this); however, I share your concerns that prevention programs may not really be addressing eating disorders as such.

I am also skeptical of prevention programs aimed at preventing eating disorders.

I think it can/might be done indirectly, as in, by reducing the rates of dieting and thus reducing the chances that those predisposed to developing EDs “uncover” the physiological effects of restricting, bingeing, or purging. Of course, not everyone develops an eating disorder as a result of dieting. My ED started with trying to eat healthier, truly. Then healthy became “too” healthy, and then calories went down, and then combined with stress/things in life, bam, I found myself with an eating disorder.

That said, I do think that teaching and educating about eating disorders will go a far way in and of itself. I think this because while I doubt EDs can truly be prevented, I do think we can improve surveillance and decrease time to intervention and diagnosis. This, of course, requires getting rid of the notion that EDNOS is a less severe version of an ED or that a reduced frequency of behaviours doesn’t warrant treatment. Or, for that matter, looking at numbers (weight loss, frequency of bingeing/purging, level of restriction) as opposed to how the person *feels* about their symptoms.

I know for me, having been taught about eating disorders the year prior to when I started really sinking into anorexia, helped me recognize the symptoms really quickly. This might be partly why I was never in denial, I sought help myself, I initiated getting a referral and the eventual diagnosis. I told people I think I have a problem before I was even diagnosable with AN. I think that was, at least in part, because we learned about eating disorders in grade 8 and those symptoms were fresh in my mind. Of course, the way we were taught about them would make me cringe right now, but you know, that’s unfortunately to be expected.

I don’t see how my eating disorder could’ve been prevented. I got treatment early, too, and I was very motivated. But, it took much more for me to get better. I know now there’s no way I could’ve recovered or gotten very far while I lived at home, for example.

Agreed- my eating disorder began similarly. I think you make a good point here about the value in reducing rates of dieting; this might facilitate avoiding the “perfect storm” of etiological factors that might lead to eating disorders among those who are predisposed.

You wrote: “This, of course, requires getting rid of the notion that EDNOS is a less severe version of an ED or that a reduced frequency of behaviours doesn’t warrant treatment. Or, for that matter, looking at numbers (weight loss, frequency of bingeing/purging, level of restriction) as opposed to how the person *feels* about their symptoms.”

THIS. Absolutely. I think that, moving forward in educating about eating disorders, this is a key consideration. I personally don’t remember ANY talk about ED-NOS or sub-clinical disordered eating in any of my health classes that included information about eating disorders. So, for the first several years of my eating disorder (and even after being diagnosed), I was convinced that I was not sick enough to warrant treatment, even in the face of many others (eating disorder-literate medical professionals included) telling me that I was.

In terms of learning about eating disorders, I think there is a fine line (and I’m not sure how to toe it) around teaching about eating disorders to increase awareness and teaching about eating disorders holding an instructive purpose for those who are predisposed to them. I think the way that information about eating disorders is taught is extremely important; so, perhaps, more attention needs to be paid to educating the teachers themselves. Of course, easier said than done…

Yeah, there definitely is a fine line. The way we were taught, or at least what I remember being taught was that it was all about trying to look thin, like a model.

I don’t think it had a role for me, but certainly I think it can easily become more instructive. I’m not sure how to get around that.

Interesting post…equally interesting commentary…Fully agreeing with both Andrea and Tetyana’s observations about the eating disorder education…and how they are presented/brought up in terms of awareness without “teaching” disordered behavior to those “pre-disposed” is critical…

I recall way back in undergrad period….having to pick a topic to research and give a speech on in my Speech 101 course…I chose “Anorexia Nervosa” …and studied all that was available at the time…from Hilda Bruch’s “The Golden Cage”…to an autobiography from Debbie Boone…you name it…all that was “available” at the time (late 70’s-early 80’s)…and I am convinced that was an unfortunate “choice” of topic for me personally.