Good health is more than just the absence of illness; it is more than just the absence of dysfunction. Good health — that is, mental, social, and physical health — requires the presence of wellness, or the ability to function well.

In this respect, with regard to eating disorders, most research has focused on assessing (health-related) quality of life and subjective well-being of eating disorder patients, often focusing on things like body satisfaction, self-esteem, and positive and negative emotions. There is, however, another way to think about well-being. A model (and assessment scale) developed by Carolyn Ruff, called psychological well-being (also here), aims to assess specific dimensions of functioning that contribute to or make-up well-being. There are six such dimensions.

Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-being:

- self-acceptance (positive self-evaluation)

- a sense of continued growth and development

- a sense of purpose and meaning in life

- a sense of self-determination and autonomy

- possession of quality relationships with others

- ability to manage life effectively (‘environmental mastery’)

I found this succinct description of the differences helpful:

Subjective well-being (SWB) is evaluation of life in terms of satisfaction and balance between positive and negative affect; psychological well-being (PWB) entails perception of engagement with existential challenges of life. (Keyes, Shmotkin, and Ryff, 2002)

It has also been suggested by Ryff and colleagues that psychological well-being is not simply the opposite of dysfunction or maladjustment (Ryff & Singer, 1996). In other words, they are not positions on two extremes of the same spectrum, they comprise two different spectrums altogether.

This makes a lot of sense to me: you can have a reduction in symptoms — or a reduction in dysfunction — without necessarily an increase in the components that make up Ryff’s PWB scale. Conversely, you can have some reductions in dysfunctional symptoms but a large increase in some of the PWB components (something I’ve definitely experienced), though, of course, the two spectrums are related.

Previous research on PWB in individuals with affective disorders found that PWB remained impaired despite a decrease in symptoms. Moreover, impaired PWB, along with the presence of residual symptoms, was associated with an increased risk of relapse (Fava et al., 1988; Fava & Tomba, 2009).

When it comes to eating disorder patients, almost nothing is known about PWB, particularly when it comes to clinical populations. To begin filling this gap, Tomba and colleagues sought to assess PWB in eating disorder patients (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder) and compare the results with healthy controls.

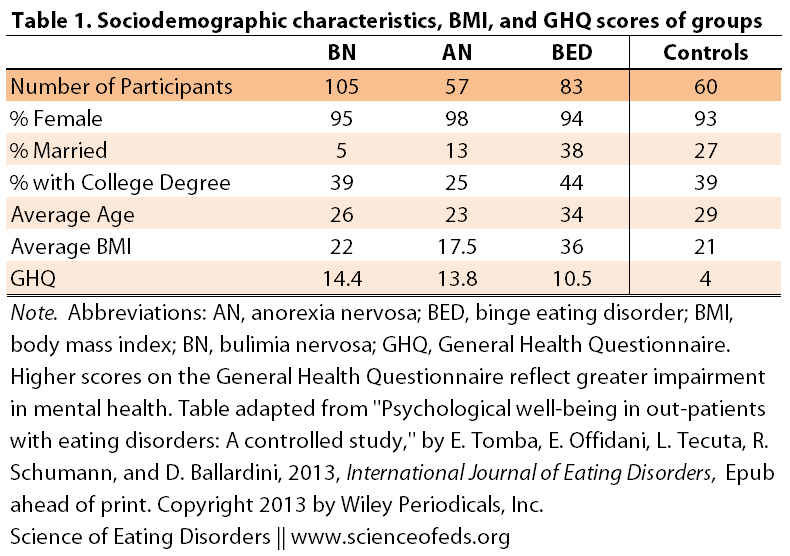

There was a total of 245 participants (11 of whom were males) and 60 healthy controls. The table below illustrates average age, average BMI, educational status, marital status, and average General Health Questionnaire scores (which is “an instrument aimed at evaluating depressive and anxiety symptoms, sleeping problems, social functioning, well-being, and coping abilities. […] Higher scores reflect greater impairment in mental health.”)

The authors assessed the participants’ psychological well-being using the 84-item PWB scale (more info on the scale here), eating disordered behaviours and attitudes using the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-40, see assessment questions here), and body image satisfaction using the BBS scale.

I’ve highlighted the main findings below.

SUMMARY OF MAIN FINDINGS I

Differences on the PWB scale between ED patients and controls:

Significant differences between groups on:

- Autonomy

- Environmental mastery

- Positive relationships with others

- Self-acceptance

With the greatest effect for the ‘environmental mastery’ and ‘self-acceptance’ components. (No differences were found for the ‘purpose in life’ and ‘personal growth’ components.)

Breaking down by eating disorder type:

- Bulimia nervosa patients scored significantly lower on all components compared to controls

- Anorexia nervosa patients scored significantly lower only in positive relationships and self-acceptance when compared to controls

- BED patients scored significantly lower on autonomy, environmental mastery, and self-acceptance components compared to controls

I’ll be honest, I was somewhat surprised to see that BN patients fared worse than AN or BED patients when compared to controls. On average, they had lower scores for all six components of the PWB. In contrast, AN patients were most like the healthy controls, and BED patients were somewhere in the middle. But perhaps it is just that I think the pattern would be different for me (if you were to assess me during the times I’d fit under the AN category, or when I was mostly bingeing without compensating.)

I wonder — perhaps the AN group scored better than the BED and BN groups because the patients themselves were in the “honeymoon” phase of restricting, before things really snowball out of control? Would there be a difference between AN in-patients and, as in this study, out-patients?

The authors suggest several factors that may contribute to the relatively positive psychological well-being of AN patients:

- Egosyntonic nature of the illness

- Lack of insight into their illness

- “A sense of self-worth, self-competence, personal mastery, and a sense of achievement” resulting from their ability of control weight

- Personality traits such as perfectionism, which may lead individuals to want to appear perfect and independent.

- “Sociocultural values such as thinness desirability and positive social feedback for being thin […] This may be particularly relevant in out-patients with AN with a non-life-threatening BMI, who may consider their thinness positively as it is associated with success and popularity.”

SUMMARY OF MAIN FINDINGS II

Association between PWB and eating disorder behaviours and attitudes:

- INCREASED maladaptive eating disorder behaviours/attitudes were associated with increased impairment on all components of the PWB with the exception of ‘autonomy’

- Among all ED patients, lower scores on the dieting subscale (a good thing, meaning less dieting behaviours) were associated with better scores on ‘positive relationship with others’ and ‘self-acceptance’

Bulimia Nervosa:

- Increased oral control scores were associated with a reduction in ‘environmental mastery’, ‘positive relationships with others’ and ‘self-acceptance’ PWB scores

- Increased dieting was associated with a decrease ‘positive relationships with others’

Anorexia Nervosa:

- Like BED patients, increased preoccupation with one’s body and with food was associated with reduced scores on the ‘environmental mastery’, ‘personal growth’, ‘purpose in life’, ‘positive relationships with others’ and ‘self-acceptance’ components

- Increased dieting was associated with a decrease ‘positive relationships with others’

- Increased oral control scores (not a good thing, meaning more dysfunctional behaviours) were found to be associated with GREATER sense of purpose in life

Binge Eating Disorder:

- Increased preoccupation with one’s body and with food was associated with reduced scores on the ‘environmental mastery’, ‘personal growth’, ‘purpose in life’, ‘positive relationships with others’ and ‘self-acceptance’ components

- Increased dieting was associated with a decrease ‘positive relationships with others’

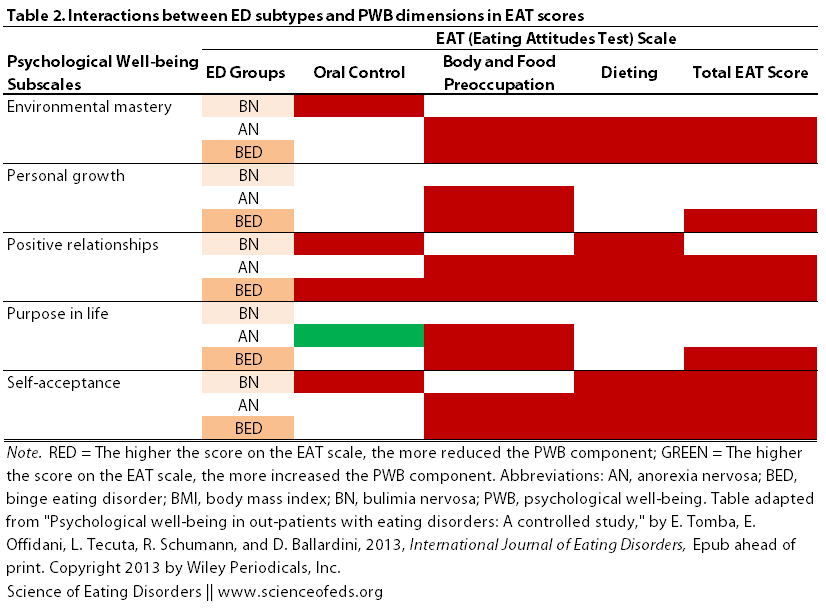

Here’s a graphical representation of the information. The red indicates that the more participants engaged in a particular behaviour (oral control, body and food preoccupation, or dieting) the worse they fared on the various psychological well-being subscales. Conversely, green indicates that the more participants engaged in a behaviour, the better they fared on the PWB scale:

So, despite the fact that BN patients were most unlike the controls on the PWB scale (scoring lower on all components), the extent of their maladaptive eating behaviours and attitudes doesn’t seem to strongly correlate with their psychology well-being. This might be because BN patients were the most homogenous group; there was little variation among the group’s members with regard to how well they fared on the PWB scale. Reduced variability makes finding relationships between traits difficult: if everyone scores pretty poorly, how can you tell if differences in one score are related to differences in another score.

It is interesting that the pattern for the BN group is almost from the patterns of the BED and AN groups.

Note, too, the only green square in the table: more oral control was associated with a greater feeling of purpose in life among AN patients, but not among BN or BED patients. This makes sense: perceived self-control with regard to diet and food intake is associated with a sense of accomplishment and self-worth, which can contribute to a sense of purpose. (I know I definitely felt that way when I first became sick with AN.)

FUTURE RESEARCH & CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

In terms of future research, well, there are a lot of gaps left to fill. As this was a preliminary study, it will be important to see how personality traits and psychiatric comorbidities play into psychological well-being. It will also be important to see how PWB changes throughout the duration of the patients’ eating disorders and recovery. It will also be interesting to see whether specifically addressing various components of the PWB will improve recovery rates and/or prevent relapses.

Given that this study is preliminary, the clinical implications of the findings are tentative. Nonetheless, I think it is important for clinicians to consider other aspects of a patient’s life — such as the components evaluated using the PWB scale — when it comes to deciding what treatment protocols to follow and, perhaps, when it is time to terminate treatment. I think it is also important for clinicians to consider, particularly in the case of AN, how some behaviours become viewed as being positive and why that may be the case. I think this realization — for the clinicians, parents, and patients — will, perhaps, improve communication and ultimately facilitate treatment and recovery.

In summary,

Participants with BN showed greater impairment in all PWB dimensions than controls. Patients with BED reported impairment in three PWB dimensions, whereas patients with AN reported only two impaired domains when compared with healthy participants. These exploratory findings may indicate a large difference between individuals with BN when compared with patients with BED and AN in lack of PWB.

And, importantly:

PWB emerged as an impaired condition distinct from other forms of distress, and its assessment may yield an increase of clinical information able to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of out-patients with EDs.

References

Tomba E, Offidani E, Tecuta L, Schumann R, & Ballardini D (2013). Psychological well-being in out-patients with eating disorders: A controlled study. International Journal of Eating Disorders PMID: 24123214

Great post as per usual Tetyana!…What struck me personally, was the fact that over TWICE of the anorexics in the study were MARRIED…(as opposed to the bulimic participants)…I wonder if the oral control might provide a sense of “mastery” or “control” in marital relationships..especially if one feels “less mastery” overall in said relationship…Interesting information to ponder…thank you for this.

This is fascinating. I think the findings make a great deal of sense, and I thank you for translating what I suspect were fairly complex findings into something more user-friendly and thought-provoking.

One thing I wonder about is how the results would have varied if they compared a younger cohort (under 30, say) with an older cohort. I suspect that some of the findings may have been very different for the older cohort, basing that on both personal experience, knowledge of friends who struggle, and having just started a FB recovery support group for adults with EDs over 40 (which is being highly subscribed to).

In this context, I think older adults may experience an alienation that would result in poorer scores in many of the subsets of PWB. Speaking of my own experience (which I do not think is uncommon), I experience almost anomie around personal growth and purpose, with grown children and a career lost to relapse – I just feel too old to start again and I am well aware of the job prospects for women my age in a youth-focused world. I struggle contantly with being dumped in therapeutic environments designed entirely for adolescent women and populated largely by adolescent women. A recent article I read commented:

““It’s also interesting that the predictors of longer-term recovery differ among different disorders and different age groups,” Lock told me.

Lock explained why some of the results differed between adolescents and adults:

Sadly there were few predictors in adults, because so few recover. The analogy is to consider the recovery rates of patients with stage 1 cancer versus stage 4 cancer. Few patients with stage 4 cancer would recover because the disease had progressed. The same is true for chronic diseases, such as eating disorders.”” (http://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2013/09/05/possible-predictors-of-longer-term-recovery-from-eating-disorders/)

(I note no recognition that you have more success with Stage 4 anything if you use Stage 4 interventions.)

Positive relationships and mastery are also difficult; my age-appropriate social circle has no way of incorporating my “weirdness” into their lives (not that they are not willing, just that they don’t “get it”), and those who do get it are usually much younger women who are also struggling with their EDs.

Anyway, thank you again.

@Spender….Would there be any way to become a part of the adult anorexia support group? I found your comment very thought-provoking and stimulating me to take some form of action…instead of reaction to the disease…I am 53 and have dealt with this for far too long…My children are also young adults…and I too feel quite “alienated” and reluctant to enter an internal treatment facility with focus on the young ED populations…Thank you in advance for any insight!