This is Part II of my mini-series on the Mandometer(r) treatment for eating disorders (link to Part I). In Part I, I provided some background on the Mandometer(r) treatment; in this post, I want to take an in-depth look at the recent Mandometer treatment study. My main goal is to see whether their data live up to their claims. Warning: This post may contain high levels of snark.

Their main claims? This is from the abstract:

The estimated rate of remission for this therapy was 75% after a median of 12.5 months of treatment. A competing event such as the termination of insurance coverage, or failure of the treatment, interfered with outcomes in 16% of the patients, and the other patients remained in treatment. Of those who went in remission, the estimated rate of relapse was 10% over 5 years of follow-up and there was no mortality.

Sounds pretty good, right? (Note the use of the word “estimated.“)

The Patients

From 1993 to 2011, Bergh et al. followed 1,428 consecutively admitted patients to the six clinics participating in this study (3 in Sweden, 1 each in Amsterdam, Melbourne, and San Diego). 1,428 is an impressive number for an eating disorders treatment study and the multi-site nature of the study is also a positive. In the last 3 years, individuals were able to self-refer themselves; up to 70% of patients now enter the treatment through self-referral.

In addition to completing several questionnaires (Eating Disorder Inventory-2, Comprehensive Psychopathological Self-Rating Scale, and a quality of life questionnaire), patients had to eat a meal without feedback to determine “speed of eating, the amount of food eaten, and their development of satiety over the course of the meal.”

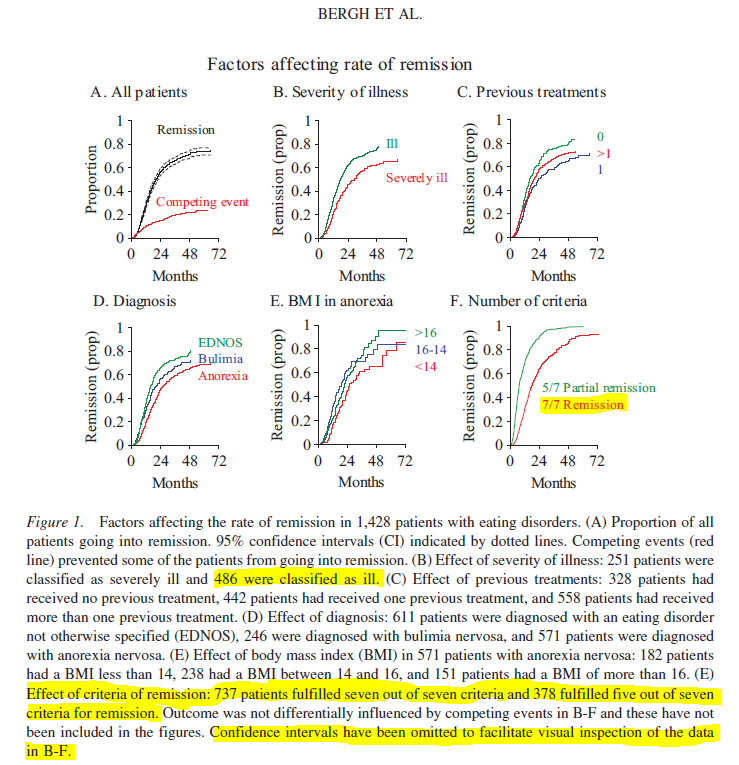

Out of the 1,428 patients, 251 were classified as severely ill (e.g., BMI <13.5, low body temperature) and were initially treated as inpatients. Overall, 40% of the patients had anorexia nervosa (AN), 17% had bulimia nervosa (BN), and 43% had eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS).

The average age was 17.5, 22.6, and 20.5, for AN, BN, and EDNOS patients, respectively. Average BMIs were 14.9, 21.5, and 18.5, for AN, BN, and EDNOS patients, respectively. AN patients had the shortest average illness duration (3.2 years) and BN patients the longest (7.4 years).

The Treatment

As mentioned in Part I, the Mandometer treatment is focused on normalising eating speed and volume, providing external heat, and minimizing physical activity. Bergh et al.:

Briefly, the patients normalize their eating pattern with mealtime feedback provided by a scale that rests under a dinner plate, connected to a small computer. By consulting a small monitor next to their plate, patients are able to compare their rate of eating in real time to that of a typical person eating that meal. The patients also develop normal feelings of satiety using the same strategy.

Initially, a behavioral therapist assists the patients, but the patients get used to the procedure rapidly and can then practice eating without the support of a therapist, including practicing at home. In addition, the patients are provided with warmth, using warm rooms, thermal blankets, or jackets to calm them and to avoid the use of calories for thermoregulation.

Their physical activity is restricted for that same purpose, and great deal of time is spent convincing and coaxing the patients to start resuming their normal social interactions. Approximately 30% of the patients were taking psychoactive drugs on admission and these are gradually withdrawn over the first months of treatment.

That’s it! It seems so easy! Why isn’t everyone on board? Why isn’t everyone as excited as this press release suggests we should be? (My favourite part of the press release: Someone apparently suggested that the Mandometer treatment is on par with the discovery of penicillin).

The study’s definition of remission was quite comprehensive and holistic (a good thing, of course): Patients were considered to be in remission when “they no longer meet the criteria for an eating disorder, when their body weight, eating behavior, feelings of satiety, physiological status, level of depression, anxiety, and obsession are normal, when they are able to state that food and body weight are no longer a problem, and when they are back at school or work. Bulimic patients must in addition have stopped bingeing and purging for at least 3 months.”

In addition, “meeting five of these criteria was regarded as ‘partial remission’ starting in 2009.” Since it doesn’t seem to matter which criteria you fulfil, you can technically be in partial remission but meet the criteria for an eating disorder (for example: have a normal body weight, normal physiological status, normal depression, anxiety, and obsessionality scores, be back to work, and state that food and weight aren’t a problem).

Now the fun part: The Results

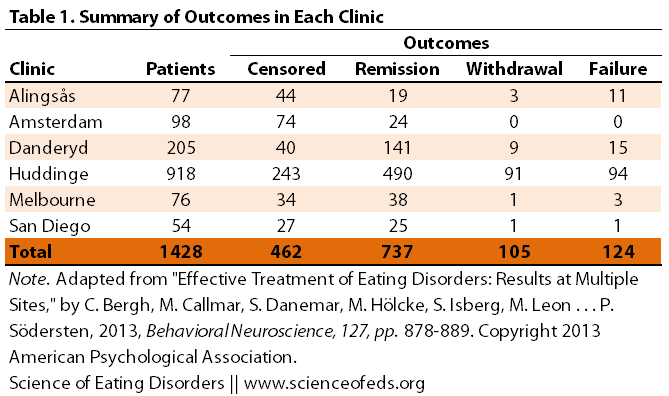

Bergh at al. dedicate three figures and one data table for the results.

The first figure shows the factors affecting the rates of remission, though it tells us nothing interesting: overall, a higher admission BMI, a diagnosis of EDNOS, and decreased illness severity predicted a faster rate of remission (Duh). What you can see in the graphs below is that as time goes on a larger proportion of patients remit. In D, for example, you can see that by 48 month for example, a bigger proportion of EDNOS patients than BN or AN patients had remitted:

I highlighted some interesting parts.

1. The authors did NOT define “ill” anywhere in the paper; they defined “severely ill,” but not “ill”. (All of the patients were diagnosed with an ED, so technically, weren’t they all ill?)

2. With the exception of the figure caption, there is NO mention whatsoever of the number of patients that fulfilled 5/7 of the seven criteria for remission. Nowhere — not even in the results table.

What’s more, the table below and everything else on remission only cites the 737 (“full remission”) number. From the wording, it sounds like an additional 378 fulfilled partial remission, but this doesn’t make any sense with respect to any of the other data the authors cite: Adding the numbers of fully remitted patients, those who were censored, withdrew or “failed” = 1,428. Where are these partial remits?

3. What seven criteria? I tried to find 7 from the blurb I quoted above on what qualifies as remission and I couldn’t count seven. Moreover, the individuals in the BN category have an additional criterion (abstaining from bingeing/purging for 3 months), is that included in the 7 (and thus AN patients only have six criteria to fill?) or it is a extra one (and thus BN patients have 8 criteria to fill)? These may seem like minor points, but this lack of clarity is unacceptable for a peer-reviewed paper.

4. This is also the first time I’ve ever seen authors omit important information (confidence intervals) to “facilitate visual inspection” without including those numbers anywhere in the paper. With a few exceptions, confidence intervals, p-values, and effect sizes are conspicuously missing from the entire paper.

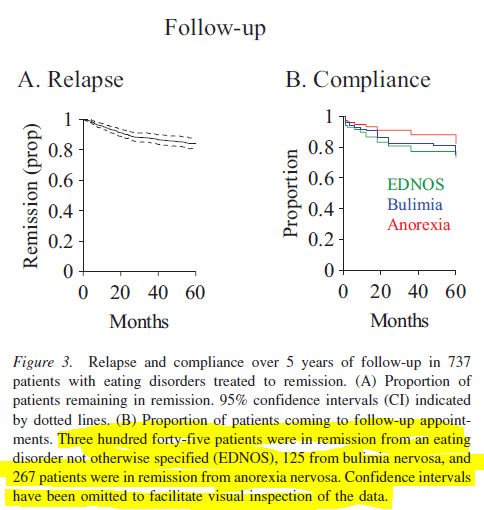

But moving on. Bergh et al. have a figure illustrating the effect of a “competing event” (in other words: insurance cut out) on treatment in the San Diego clinic. The final figure shows the proportion of patients who have relapsed over 5 years:

The study recruited patients up to 2011, so I wonder how they got 5-year follow-up data from those admitted in 2010 and who, say, remitted in 2011? Are these researchers psychic?

And now, the grand finale. The final and only table that shows treatment outcomes:

The second column shows the number of patients in each clinic. The remission column shows the number of remitted patients. Note that there’s no information on partial versus full remission. Where do those 378 partially remitted patients fit?

Data from patients who were still in treatment or who dropped out for unknown reasons were censored. The effect of a “competing event,” which interfered with the possibility of going into remission, was analyzed using cause-specific hazard functions and corresponding cumulative incidence estimators (Gray, 2011). Competing events included instances when patients withdrew because they felt that they were not improving, when they were diagnosed with an unrelated illness, or when they withdrew because of financial constraints. That is to say, incidents that were either related (treatment failure) or unrelated (e.g., insurers did not pay) to the therapy could prevent the patient from completing the treatment and were therefore considered competing events.

This part of the paper really infuriated me:

Patients withdrawn for reasons unrelated to the treatment were censored at the time when they were no longer in treatment. Failure of insurers to pay for treatment in San Diego provided an example and explained why 50% of the patients were censored in this clinic (see Table 3). Patients withdrawn for reasons related to the treatment, that is, the treatment failed, were retained in the analysis, “burdening” the denominator in the calculation at all times, thus yielding a conservative estimate of the rate of remission.

First of all, Bergh et al. keeping pointing to insurance as a reason for “censorship” but this only really applies to the US clinic (which made up a paltry 4% of the total sample). What about the other places?

But more importantly, keeping the patients who withdrew because treatment failed or for reasons related to treatment does NOT yield a conservative measure! How else would you calculate the percentage of patients who have remitted if not by looking at the proportion of those who remitted out of the total number of patients who entered the study, which includes those who haven’t remitted because treatment did not work? Including those who haven’t remitted because “treatment failed” does NOT IN ANY WAY make the measure “conservative.”

Their way of calculating the probability of going into remission (“life tables” and survival analyse) yielded interesting numbers:

In Amsterdam, where 98 patients entered treatment, 24 remitted. Bergh et al. calculated that the probability of going into remission in this clinic was 64%. In Danderyd, 205 patients entered treatment and 141 remitted. Bergh et al. calculated that there’s was an 86.4% chance of going into remission. In Huddinge, 918 patients entered treatment, 490 remitted. The probability of going into remission in this clinic was, according to Bergh et al., 74%.

Now, I’m not a statistician. Not even close. But it seems disingenuous to calculate remission rates this way. After all: 24/98 = 24.5% (not 64%); 141/205 = 68.7% (not 86%); 490/518 = 53.4% (not 74%). This is how they get an “estimated” 75% remission rate when only 51.5% of the initial sample remitted (737/1428 = 51.6%).

This study also did not have a control group — so we can’t compare the Mandometer Treatment to another treatment protocol or even a waitlist control. How many of these patients would recover without the Mandometer? We don’t know.)

I’ve never seen life tables used in an eating disorders treatment study. Now that might be because I haven’t read enough studies, but you do have to wonder why, in 2013, Bergh et al. would chose to use a non-standard way to analyse a treatment study of this nature? Survival analyses have many uses, but as far as I’m aware, this isn’t one of them. (Please correct me if I’m wrong, though.)

[EDIT: A friend told me of a treatment study from a group in Toronto that used survival analyses to evaluate time to remission (or relapse? can’t recall). She will link me to the study so I can compare the calculations. So, correction: they are used, but not that frequently.]

Bergh et al. also didn’t use the standard/most commonly used questionnaires to evaluate anxiety, depression, and obsessionality. Instead, they used a questionnaire that another group found underestimated the levels of anxiety, depression and obsessionality.

AND AS IF THIS ISN’T ENOUGH…

Guess what.

This might be the FIRST treatment study I have ever seen that had no information whatsoever (anywhere!) on the remitted patients (with the exception of the “estimated” 10% relapse rate, though they just show it in the figure and provide NO follow-up date).

Bergh et al. provide NO information on:

- The extent of weight restoration in remitted patients (no BMI values or % of expected body weight or any kind of metric that enables readers to compare the participants’ weight before and after treatment

- The levels of anxiety, depression, and obsessionality in remitted patients

- Eating Disorder Psychopoathology (EDI-2) and Quality of Life measures (actually, these were NOT reported before or after treatment, though the authors said they collected the data)

- Menstrual status

- Symptom frequency

- The proportion of individuals who have jobs or go to school (recall this was one of the seven criteria for remission)

- Comorbid disorders anywhere — before or after — and you’d think for researchers who claim that comorbid psychopathology is the result of malnutrition and exercise, they’d want to provide data to show how comorbid psychopathology decreased following treatment

LET’S RECAP, SHALL WE?

Bergh et al.:

- Did not have a control group

- Did not have clear remission criteria

- Did not use standard approaches to calculate remission

- Did not report post-treatment data for assessments of anxiety, depression, and obsessionality (except for the 13 patients that dropped out of the San Diego clinic)

- Did not report eating disorder pathology, menstrual status, or symptom frequency before or after treatment

- Did not report any information on psychiatric comorbidities

- Did not provide information on any remission criteria in patients who remitted (extent of weight restoration being a crucial one), with the exception of relapse rates

- Did not provide clear information about the partially remitted patients (only mentioned the number in a figure caption) and it is unclear where those patients fit (as the numbers don’t add up)

- Did not include confidence intervals for the vast majority of the data (not even in text!)

- Did not have any statistical analyses for anything in the study with the exception of the data shown in the figures (i.e., EDNOS patients took significantly less time to go into remission than AN patients)

Did BMI values change significantly after treatment for those who remitted from AN? Where the supposed decreases in anxiety, depression, and obsessionality following treatment scores significant? Did the quality of life improve in the patients who remitted? We don’t know. There’s ZERO information on any of this.

Sigh. In the next post I’m going to critically analyse the dozen or so reasons why Bergh et al. claim that eating disorders are not mental disorders (or, in their words, “have no underlying psychopathology”). Join me for the ride.

References

Bergh C, Callmar M, Danemar S, Hölcke M, Isberg S, Leon M, Lindgren J, Lundqvist A, Niinimaa M, Olofsson B, Palmberg K, Pettersson A, Zandian M, Asberg K, Brodin U, Maletz L, Court J, Iafeta I, Björnström M, Glantz C, Kjäll L, Rönnskog P, Sjöberg J, & Södersten P (2013). Effective treatment of eating disorders: Results at multiple sites. Behavioral neuroscience, 127 (6), 878-89 PMID: 24341712

These results by Bergh and colleagues are actually impressive. For example, 1,428 patients were treated, and there were zero deaths. This is better than standard treatment. Also, more than half the patients reached a normal body weight within 12 months, a result that generally isn’t achieved by treatment as usual. While Tetyana’s criticisms have some merit, her points apply to virtually all published studies of eating disorder treatments, and are not limited to Mandometer. I urge people, therefore, to read the Bergh paper and draw their own conclusions. Behavioral Neuroscience 2013 Vol. 127, No. 6, 878-89. I also think that Bergh makes a good point when she questions whether anorexia nervosa is necessarily a “mental disorder.” When endurance athletes develop anorexia nervosa, a strong argument can be made that they have a biologically-based condition (activity based anorexia) not a mental disorder. Of course some people with AN will have a “mental disorder” but not all do.

Hi CB,

Thanks for your comment. I agree with you on one part: The results *would have been* impressive if Bergh et al. ACTUALLY provided evidence to support their claims. Alas, as I’ve explained in detail in the post: They didn’t.

For example, 1,428 patients were treated, and there were zero deaths. This is better than standard treatment.

Not really.

1. 1,428 patients entered the study, but many dropped out within the first 3 months of treatment… hardly qualifying as being “treated.”

2. Only 737 patients were followed-up, so there were zero death among those 737. The authors did NOT follow up on the other 691, so how could they know whether there were any deaths?

3. This is actually not better than standard treatment and not impressive. Most papers do not mention deaths because they don’t occur. Bergh et al.’s focus on “zero deaths” is something that will *Wow* a reader who is unfamiliar with ED treatment studies of this nature. There were no deaths in: the Zipfel et al. (2013) study; le Grange’s FBT study; Fairburns CBT-E in adults with anorexia study. And unless I missed something, no deaths in this, this, this, this, this, this, this, or this treatment study either. I can keep going. (I admit, I didn’t look thoroughly into all of the papers I linked to above, though I’ve read some, but an instance of death is usually noteworthy enough to mention in the abstract.)

I particularly liked these three studies I came across (not linked above):

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17537071

“Overall there was little to distinguish the two treatments at 5 years, with more than 75% of subjects having no eating disorder symptoms. There were no deaths in the cohort and only 8% of those who had achieved a healthy weight by the end of treatment reported any kind of relapse.”

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19105062

“At the 36-month follow-up, 75% of the patients were in full remission with reduction in eating disorder symptoms and internalizing problems and they experienced a less distant and chaotic atmosphere in their families.”

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16864523

“Sixty percent of the total sample and 72% of treatment completers had “good” outcome (defined as maintaining weight within 10% of average body weight and regular menstrual cycles) at post-treatment and at six months follow-up.”

Also, more than half the patients reached a normal body weight within 12 months, a result that generally isn’t achieved by treatment as usual.

Not really.

1. Probably just around half or a bit less than half of the starting sample STARTED OUT at normal body weight. The authors do not provide clear data but 17% of the patients had bulimia nervosa and had normal body weight to begin with and 43% had EDNOS (average body weight was 18.5), meaning that roughly half were above that. The authors don’t provide sufficient information on this (a problem in and of itself!), but one thing is for sure: Not all of the patients were underweight from the start.

2. Perhaps you mean more than half of the AN sample reached normal body weight within 12 months? A look at Figure 1 E. suggests that’s not the case. It seems that by 24 month those starting with BMIs > 14 achieved weight restoration. However, the authors only provide those hard-to-read graphs with no numerical data (unless I’m overlooking something), so it is hard to make conclusions. I re-skimmed the paper to see if I missed anywhere where they mention what you wrote but couldn’t find it. Please point me to it in the case that I missed it.

3. I don’t see any basis for stating that this isn’t achieved with TAU. If anything, the one thing treatment is good for *is* weight restoration and the expense of focusing on psychopathology in general.

While Tetyana’s criticisms have some merit, her points apply to virtually all published studies of eating disorder treatments, and are not limited to Mandometer.

Virtually all studies? I invite you to show me other eating disorder treatment studies that:

– Do not report eating disorder pathology, menstrual status, or symptom frequency before or after treatment

– Do not provide information on any remission criteria in patients who remitted (extent of weight restoration being a crucial one), with the exception of relapse rates

– Do not not include confidence intervals for the vast majority of the data (not even in text!)

– Do not provide statistical analyses comparing pre and post treatment assessments — no effect sizes anywhere, either.

– Do not include data for assessments that were done (like EDI-2)

Even Fairburn’s CBT-E in AN adults study which was NOT randomized used intent-to-treat analyses (which is for randomized controlled trials, generally). CB, I urge you to point me to more studies that provide as little data on important metrics as this study. Many studies are uncontrolled, this is true, and many probably don’t analyse remission in the ideal way, but the failure of this study to provide even the basic information is truly astonishing.

I also think that Bergh makes a good point when she questions whether anorexia nervosa is necessarily a “mental disorder.” When endurance athletes develop anorexia nervosa, a strong argument can be made that they have a biologically-based condition (activity based anorexia) not a mental disorder.

Yes, her points may seem convincing when one doesn’t have a background in neuroscience and behavioural psychology, I agree. This is because she selectively includes papers that seem to support what she says, while excluding the plethora of data that doesn’t. It is also because she cites papers that actually don’t support her findings (see my past post), and because she makes false comparisons (more on that in the next post).

Secondly, could you please explain to me how a mental disorder is not a biologically-based condition? Everything that is “mental” (i.e, in the “brain”, has biological correlates).

As I wrote on my Tumblr earlier:

“Behaviours and cognitions have biological correlates. It is just how it works. It is a fact. Thus, all mental disorders have biological correlates. Whether or not they have biological causes is a different matter. But all evidence thus far points to the fact that thoughts, feelings, and behaviours have neurobiological correlates. Without a nervous system, organisms (including humans), cannot think, feel, or behave.

I’m not aware of any research that convincingly suggests otherwise.”

Activity-based anorexia is a rat model of anorexia nervosa. We cannot make parallel comparisons to humans (again, more on this later).

Finally, doing an endurance sport or a weight-focused sport can provide the environmental “trigger” (for a lack of a better word) and interact with the biological predispositions to lead to AN. BUT here’s the issue:

Why do only SOME endurance athletes develop anorexia nervosa? Why do only some athletes in weight-focused/image-focused sports develop anorexia nervosa? The answer: Biological predispositions to develop the disorder.

Why do many who do NOT do endurance or weight/image-focused sports develop anorexia nervosa? Ah, well, the entire blog is dedicated to trying to answer this question. I invite you to read some other posts by myself and others.

Whether we call something a “disorder” or not is not a scientific question. We call something a disorder if society deems it to be maladaptive and/or sufficiently deviating from the so-called “norm.” THIS doesn’t have ANYTHING to do with the fact that ALL behaviours and cognitions have biological correlates.

Hi Tetyana,

In response to your comments:

1.While it’s true that several other studies also reported no deaths, none of the studies you cited involved numbers as large as the recent Mandometer paper. For example, among those you cite, Zipfel involved 242 patients, LeGrange 121, and Eisler 40. The Mandometer paper, by contrast, included 1,428, a much larger population. There is no evidence that the researchers followed up with only 737 of the patients, as you claim. The absence of reported deaths is good news. The mortality rate for standard care appears to range from 6.2 to 17.8%.

2. The Mandometer data does show, as I wrote, that “more than half” the patients enrolled reached normal weight within 12.5 months. There were 1,428 patients enrolled. 737 met the criteria for remission. Table 3. The criteria for remission required a normal BMI between 19 and 24. (see p. 880) The treatment was carried out over 12.5 months. This means that 51% reached normal weight, as defined, within 12.5 months. This represents a significant finding. Before treatment, the median BMI in the AN group was 14.9 and the quartile range was 13.8 — 16.1.

3. As you note, in addition to those patients who reached full remission, others reached partial remission. The paper doesn’t tell us how many reached partial remission, but that doesn’t detract from the number who reached full remission.

4. The number of patients whose data was “censored” included those still in treatment. (p. 881) Since these patients were still in treatment, they were not included in the denominator. Doing so would have been misleading.

5. The Mandometer data is convincing to many people who “have a background in neuroscience.” The Karolinska Institute is one of the most respected research universities in the world.

6. The Mandometer authors make a convincing argument that the best treatments target weight restoration and normalization of eating patterns, not supposed “underlying” psychiatric problems. In this respect, Mandometer is similar to FBT. In Mandometer, a computer takes over for the patient decisions with regard to the patient’s eating patterns. In FBT, the parents do. The theory is that for the majority pf patients (not necessarily all) the “underlying” psychiatric problems tend to resolve with weight restoration and resumption of normal patterns of eating. Data from the FBT studies support this theory.

7. You fault Mandometer for not including “group therapy.” Is there convincing evidence that “group therapy” is effective in the treatment of anorexia nervosa? Are there RCTs demonstrating this?

8. The authors of the Mandometer paper actually make relatively conservative claims. In the conclusion to their paper, they suggest future studies to compare Mandometer treatment with standard care in randomized controlled trials. Given this new data, the effectiveness of Mandometer is promising enough that the next stage, RCTs, would be appropriate. Until an RCT comparing Mandometer with TAU is conducted, it’s unwise to brand Mandometer as “snake oil.”

CB,

1. Yes, the number of patients is impressive, no doubt. I wrote about that in this post and in the last post. It is unlikely that they were able to follow-up on all the participants who enrolled. Thus, they need to be clear about how many they followed-up on and how many they lost to follow-up, as that is what every other study of this nature does. This is not a news article for the Daily Mail. It is a “peer-reviewed” article; there are standards. (I write peer-review in quotes because I’ve never seen such a poor paper pass through peer-review in the last 8 years I’ve been reading papers in neuroscience, genetics, and psychology.)

2. You forgot about the bulimia nervosa and EDNOS groups.

3. WHOA. It is not that it “doesn’t tell us”, it is that it leaves 378 patients UNACCOUNTED FOR. IT says 378 patients reached partial remission in a figure caption but LEAVES THESE PATIENTS UNACCOUNTED FOR IN TABLE 3. There is literally data missing here.

4. This doesn’t make sense since by my calculations, all of the patients who are still in treatment were listed as “Failures.” (I did the calculations.)

5. First, who are these “many people”? And how many of these “relevant people” have appropriate backgrounds to judge this paper? Second, it doesn’t matter that Karolinska is a respected place. It is very well respected. Harvard is too, but it doesn’t mean Harvard doesn’t have it quacks (re: Mark Hauser, for one). Andrew Wakefield worked in respected institutions too. You are wrong to assume that Karolinka’s reputation has ANYTHING to do with the validity of THIS PAPER. It doesn’t work this way in science. It is illogical to claim that just because Karolinka is a great institution, this paper, since some of the authors (namely the last author) are affiliated with it, means this paper is good. Check out the Retraction Watch blog: Do those papers only come from crappy institutions? No.

6. Most treatments target weight restoration and normalization of eating WITHOUT making ridiculously unsupported claims about everything else. Since you are fond of FBT, compare RCTs of FBT and the quality of the data in those studies with this one. Compare Lock and le Grange’s data analysis and reporting of remission data with this study. Look closely at what and how the authors of these studies report their data and do their analyses. Weight restoration and normalization of eating habits is the number one priority for IP, OP, and residential treatments. Everything else is important but not as prioritised. FBT has been shown to work for a subgroup of individuals: Mainly those who are young and have been sick for a very short amount of time. This is great, of course, but it is not something that will work for everyone. It is a tool. FBT, however, doesn’t make unsupported claims about hypothermia or fallacious comparisons to ABA.

7. I don’t fault them for not including group therapy.

8. HA!!! They had 1,428 participants in this study. Why didn’t they do an RCT? Even a waitlist control? Why is it that from their ONLY RCT published by them, they chose to include data ONLY from 16 people?!! They sound like acupuncture and homeopathy proponents, always touting the need for more data.

This is Grade A snake oil. I would not be surprised if this paper follows the trajectory of Wakefield’s infamous Lancet paper.

I’m not going to repeat the same stuff I wrote earlier, again.

Tetyana,

You are faulting the Mandometer paper for failing to do something it was not intended to do. The paper was not intended to be a randomized controlled trial testing Mandometer against another form of treatment. Instead, it was intended to address several specific criticisms that have been made against Mandometer, including criticism that it 1)would cause many deaths, 2) could not possibly lead to remission, and 3) cannot be effectively disemminated beyond where it was developed. This paper proves those three points wrong. There was no widespread mortality, hundreds of patients recovered, and rates of remission were roughly equivalent at the several sites involved. The authors now recommend randomized controlled trials testing Mandometer against other forms of treatment. That seems pretty reasonable to me.

As you know, there are actually very few RCTs in the entire body of literature on treatment of AN. With regard to adolescent patients, there are fewer than a dozen. The entire field, therefore, deserves blame for this state of affairs; if you call Mandometer snake oil because it hasn’t been systematically studied in RCT’s, you would need to apply that label to virtually the entire field of eating disorder research.

I am well aware of shortcomings within academic science. I have written to journal editors asking them to retract some of the articles they have published in eating disorder journals. I don’t think the Mandometer paper, however, is any better or worse than most.

While you and I disagree on interpretation of the Mandometer data, that’s OK with me. I interpret eating disorder research with the help of my spouse, who has a PhD in neurobiology from the University of California. She is well qualified to interpret research studies.

My kid had AN as a teenager several years ago. My spouse and I studied the research literature and our whole family put together a plan for helping our kid beat the anorexia. She has been completely recovered for many years. That’s one reason I like the principles of FBT. However, if FBT isn’t available for some sufferers, Mandometer might be a reasonable option, until something better comes along.

Regards,

CB

I’m very curious as to what data are convincing to those that have a “background in neuroscience.” I’m an all-but-dissertation behavioral neuroscientist (specializing in the neurobiology of addictive behaviors), and I found the interpretation of the present data in relation to ABA studies to be disingenuous and far-reaching. Furthermore, one cannot interpret the studies in bulimic and EDNOS patients using ABA models where food intake is restricted and substantial weight loss occurs. I cannot imagine getting a paper accepted that would draw such far-reaching parallels between rats and humans. If you have evidence to convince me otherwise, please let me know! I’m really curious.

I’m not faulting it for not being an RCT; though I’m not sure why they didn’t do an RCT since that’s what they alluded to in their previous papers (Bergh et al., 2002). Indeed, they had a study with a control (waitlist) before: Why not repeat that? 11 years after claiming that basically the next step is an RCT, or at least a larger controlled study, they published a large paper but without a control group? What gives?

I’m not faulting it for not being an RCT; I’m faulting it for not doing proper statistical analyses, not reporting relevant data (a lot of relevant date is missing), not being clear in remission criteria, and something missing 378 patients from their tally. I feel like a broken telephone, saying that same stuff over and over again.

I’m happy your daughter recovered. That’s great. It is, however, an n=1.

And by the way, I never said Mandometer treatment couldn’t possibly lead to remission. Of course it can: they focus on refeeding and decreasing exercise. Key components of AN treatment. I mentioned either in this post or my past post that many times in my own recovery I wanted something to help me learn how to eat again (i.e., like the Mandometer gadget thing). I also think their focus on social life is worthwhile. I have no doubt it leads to remission.

This doesn’t negate that this paper is terrible when it comes to data reporting and data analysis. Point me, CB, to a paper in the last 5-10 years on a treatment of anorexia nervosa where the authors omitted information about BMI values and/or % EBW? Why did Bergh et al collect EDE-2 data and not report it anywhere? Why did they collect QofL data and not report in anywhere: They cannot claim that there were improvements in this measures without showing evidence. I am not surprised if there were improvements, but I am skeptical of their lack of transparency.

You are conflating things. I’m not so much skeptical of the treatment (Again, I think weight restoration, resumption of normal eating, and decreasing exercise are crucial in AN recovery), I am critical of their data and its poor quality. I certainly think Mandometer would compare favourably to thinks like dance/art/equine therapy and stuff. Why? The former focuses on weight restoration and resumption of normal eating, the latter don’t. That has NOTHING to do with the poor and sketchy quality of data in this paper.

Just as I am sceptical of the DBS paper I posted about earlier: They suspiciously omit a lot of important information. And just as I’m critical of Fairburn’s overreaching claims in their CBT-E study that lacked a control group. It doesn’t mean the study is useless, though.

Anyway. This is futile. I appreciate your feedback but I can’t keep repeating myself over and over again.

Tetyana well done for putting this out there. I looked at Mandometer treatment for my daughter in the Melbourne clinic, and came up with even less data than you. Like you I was unimpressed.

In Australia (Melbourne), the treatment is funded out of patient’s pockets, only inpatient care is significantly covered by insurance. This is of course designed as an outpatient treatment.

I think the saddest thing is that, I have heard reports that this is the only treatment funded by the government in Sweden.

Hi Bronwen,

Thank you for your comment.

I think the problem is that most people don’t look to far into evidence for particular treatments (which they should, especially when they make claims that sound too good to be true). It is unfortunate. Reducing exercise and establishing normal eating patterns are of course crucial, and maybe the gimicky Mandometer helps some people with that (I wouldn’t be surprised), but it is all of the other BS that comes with this treatment (no individual therapy, no group therapy, the overblown claims of the prevalence of hypothermia, the lack of good studies). But of course, this is reported on their website as a study showing 75% remission rates!

So, in Australia, even outpatient would be funded by the patient? Like outpatient in an Adolescent ED unit in a hospital? I think we’ve discussed treatment in Australia before, but I don’t remember as much as I should. I also assume it is similar to Canada’s or UK’s systems. Would this be funded by the patient because it is not administered by the government health services?

:/ Not sure about Sweden, I should look into that. If it is the case, it is unfortunate but not the worst case scenario: At least they focus on normalizing eating and reducing physical activity. I suppose patients could seek psychotherapy elsewhere. Their policy of weaning everyone off of medication is worrying though.

I am still astonished as to how this was published the way it was written up.

Looking forward to the next post, especially in regards to the over-reaching claims that rat ABA is just like human eating disorders (all of them, not just anorexia, of course!).

Indeed, I’m astonished too.

I may ask for your help in that (with regard to the parts about ABA), given that you are the expert on rat models of human behaviour!

Anytime 🙂

The Mandometer method is not the only treatment method for EDs covered by insurance in Sweden. Actually the method is not even close to mainstream.

In Sweden eating disorders are considered to be psychiatric disorders and are treated as such.

Good to know, thank you! Is it popular/well-known there? (It is so hard to assess/know as an outsider living in a different country.)

It’s well-known, popular among some, but also in Sweden questioned and criticised by professionals in the field of EDs.

Of course Mando is questioned and criticized by certain professionals. It goes against their prejudices. However, is there experimental data developed in Sweden showing that the “psychiatric” model is resulting in better outcomes?