Although the words “anorexia nervosa” typically conjure up images of emaciated bodies, eating disorders characterized by dietary restriction or weight loss can — and do — occur at any weight. However, precisely because anorexia nervosa is associated with underweight, doctors are less likely to identify eating disorders among individuals who are in the so-called “normal” or above normal weight range, even if they have all the other symptoms of anorexia nervosa.

Clearly, this is a problem.

For one, there is no evidence that eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) — a diagnosis given to individuals who do not fulfill all of the criteria for anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa — is less severe or less dangerous than full syndrome anorexia nervosa. As I’ve blogged about, individuals with EDNOS have comparable mortality rates (see: EDNOS, Bulimia Nervosa, as Deadly as Anorexia Nervosa in Outpatients) and similar (sometimes even more severe) levels of psychopathology (see: Are There Any Meaningful Differences Between Subthreshold and Full Syndrome Anorexia Nervosa? and, to a lesser extent, Think You Are Not “Sick Enough” Because You Didn’t Lose Your Period? Read This.)

In one study, Rebecca Peebles and colleagues (2010) found that “adolescents who lost greater than 25% of their [former] weight but who were above 90% of median body weight for their age had lost a significantly higher percentage of their body weight and at a faster rate, when compared with adolescents with anorexia nervosa (AN) who had a BMI in the underweight range.” Importantly, these adolescents were “more medically compromised than the patients presenting at a much lower median body weight.”

Similarly, among adults, it is the degree of weight suppression (the difference between one’s current weight and highest past weight) that “corresponds to more severe symptoms of AN, as well as binge eating, depression, and menstrual abnormalities” (Berner et al., 2013).

Importantly, because eating disorders among individuals who don’t present at a low BMI are more likely to be missed or be seen as less serious, these individuals are likely to suffer for longer before receiving appropriate treatment. This is particularly worrying because early identification and short duration of illness are the biggest predictors of successful treatment and full recovery.

Given the importance of this issue, Jocelyn Lebow and colleagues wanted to examine the prevalence of a history of overweight or obesity among individuals adolescents and young adults seeking treatment for a restrictive eating disorder. (Lebow and colleagues previously published a report of two teens whose eating disorders were missed as a result of their weight. Kristin Javaras of the UNC Exchanges blog wrote about that report here.)

To do this, they analyzed medical records of patients seen at a speciality clinic over a period of about 6 years. They excluded patients who did not qualify for an eating disorder diagnosis, whose eating disorders were primary characterized by binge eating and/or purging in the absence of weight loss or, in the words of the authors, “successful restriction,” and those with incomplete weight histories.

After excluding those individuals, they were left with 179 patients. The patients ranged from 10 to 20 years, with an average age of just slightly over 15. So, what did they find?

SUMMARY OF MAIN RESULTS

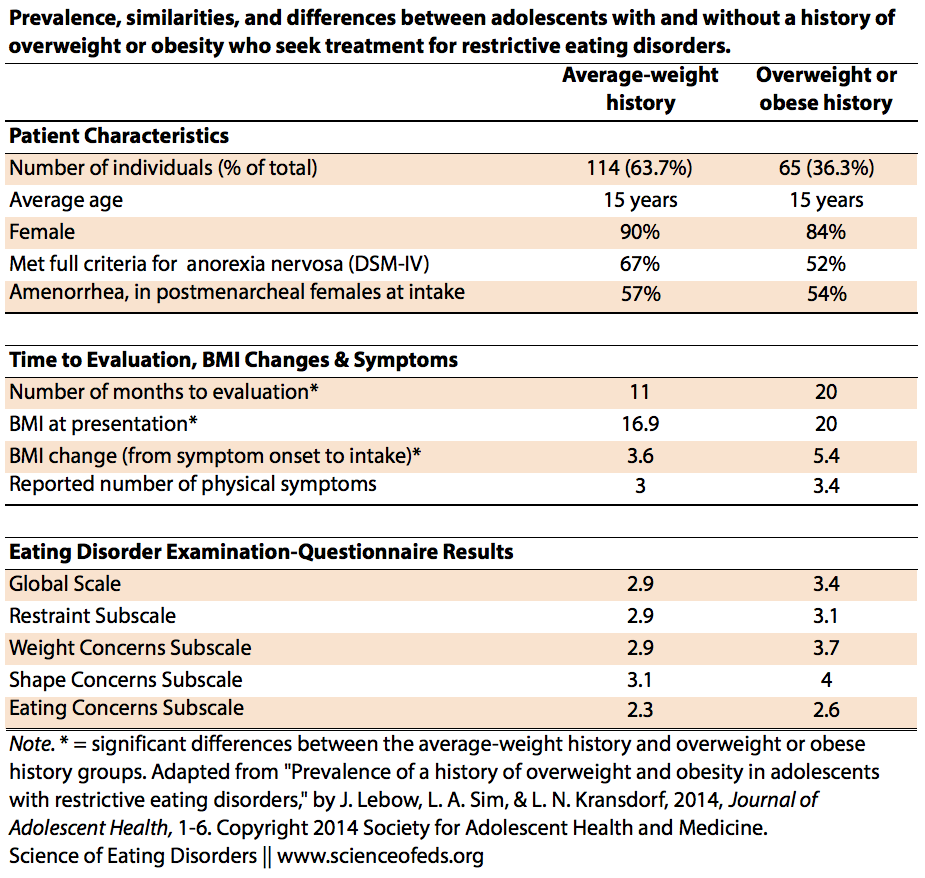

- Over 1/3 (36%) of patients seeking treatment for a restrictive eating disorder had a history of overweight or obesity

- 1/2 of those with history of overweight or obesity, compared to 2/3 without, met the full criteria for anorexia nervosa

- There were no differences in the presence of amenorrhea (lack of menses) among the two groups

On average, compared to their average-weight history counterparts, patients with a history of overweight or obesity:

- Had a longer duration of illness prior to being seen at the ED clinic (20 months versus 11 months!)

- Had lost more weight by the time they were evaluated for an eating disorder (A BMI drop of 5.4 vs. 3.6)

- Reported the same number of physical symptoms

- Did not differ in eating disorder symptoms as assessed by the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire

Below is a table summarizing the data:

It is important to note that because this study was based on a medical chart review of treatment-seeking adolescents, the findings likely underestimate the actual prevalence of restrictive eating disorders among previously overweight and/or obese individuals. In addition, because patients were asked to self-report highest weight and symptom onset, it is impossible to ascertain the accuracy of this data, particularly given recall bias.

SUMMARY

Lebow et al. found that among individuals seeking help for a restrictive eating disorder at their clinic, 36% had a history of overweight or obesity. Although those individuals were more likely to present at a “healthy” weight, they exhibited similar levels of eating disorder pathology and had a similar number of physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue, cold intolerance, dental caries, constipation, osteoporosis, bradycardia, dizziness, lanugo, etc.) compared to adolescents without a history of overweight, who typically presented in the “underweight” BMI range.

IMPORTANCE & CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

As the authors state,

These findings underscore the danger of emphasizing weight as the sole indicator of health and the importance of assessing a patient’s physical functioning or symptoms rather than body weight to determine their health status. . . . Providers must recognize that serious restrictive eating disorders are possible in youth presenting at any BMI. . . . By eliminating the faulty assumption that obesity and restrictive eating disorders are mutually exclusive diagnostic categories, health care providers can begin to increase early detection of eating disorders in adolescents with a history of overweight or obesity and minimize the substantial negative impact of these disorders on patients’ health and well-being.

Thankfully, the recent edition of the DSM-5 has eliminated the weight criterion, defining low weight in relation to every individual’s growth trajectory. However, only time will tell whether these changes will lead to better recognition of restrictive eating disorders among individuals who don’t present to the clinic at very low BMIs. It is also unclear (to me) how clinicians will apply the new guidelines (and how many are even aware of them)? I think better recognition of eating disorders among individuals who don’t fit the stereotype will not only depend on changing doctors’ perceptions of eating disorders and eating disorder sufferers, but also changing the perception of the general public and of other eating disorder sufferers as well.

References

Lebow, J., Sim, L., & Kransdorf, L. (2014). Prevalence of a History of Overweight and Obesity in Adolescents With Restrictive Eating Disorders. Journal of Adolescent Health DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.06.005

Im so glad studies are being conducted on this. My ED went undetected for 15 years for this exact reason -weight not low enough and my period came back after starting birth control… (again, docs started me on bc to get my cycle back and never thought of the possibility of an eating disorder).

Thanks for your comment Jill. I am really glad that there are studies being conducted on this too, and I hope that they will contribute to increasing awareness, particularly among doctors and health care workers. I am sorry that you’ve had to deal with that 🙁 :(.

Thanks Tetyana. The good news is I am finally in recovery and working hard every day!

That’s awesome to hear!

Thank you for posting about this. I presented to my GP with a BMI of 18, (previously BMI 24) with some fairly classic symptoms of a restrictive ED / AN (amenorrhea, purple finger nails from feeling cold, weakness, dizziness). The doctor suspected anemia, but didn’t ask a single question about my eating habits, attitudes to weight etc.

Admittedly, I didn’t disclose my restriction – because I believed that as I wasn’t objectively underweight, I couldn’t have a ‘real’ eating disorder.

Was ‘average weight history’ considered as BMI <25? I feel like these findings could apply to anyone for whom dropping 3-4BMI points doesn't give them a BMI 17.5. As well, people who develop restrictive EDs when overweight are sadly likely to even be encouraged in their efforts to lose weight if their ED is not detected.

Anyway, I hope, as you say that more awareness on this will follow, but I think it will be hard to shake the weight criterion from peoples' minds while EDs in the DSM are so category based.

Really appreciate you getting this message out. Ten years ago, our family doctor didn’t take my daughter’s condition too seriously and said as long as she’s over 100 pounds she’s fine. Shortly thereafter, she was admitted to an ED day program …..staff said she was one of the most serious cases they’d ever seen and they didn’t think day treatment would be enough and sought a bed at HSC. Dr. said her heart beat was abnormal and, had we not got treatment when we did, he gave her 3 weeks before her heart gave out. Keep on spreading the truth!

Thank you.I have had restrictive eating for almost a year,not one doctor I have seen was concerned as I am slightly overweight.I ended up diagnosing myself and am seeing a dietician.Still struggling to eat enough as I feel fat…..

I hope that doctors start realizing–sooner rather than later–the seriousness of restrictive EDs and fewer people have to go through your experiences. I hope you are doing better now? (Apologies for the major delay in responding!)