Should eating disorder patients be introduced to “junk food” or “hyper-palatable” foods during treatment? A few days ago, I stumbled across a blog post where Dr. Julie O’Toole, Founder and Director of the Kartini Clinic for Disordered Eating, argues against introducing “junk food” during ED treatment. The crux of the argument is that “hyperpalatable foods”—e.g., chips and Cheetos—are not real food and should never be forced or encouraged for anyone, regardless of the presence of an eating disorder:

A lot of ink has been spilled on teaching Americans in general and children in particular to make good food choices. Just because you have anorexia nervosa as a child, and desperately need to gain and maintain adequate weight, does not mean that you will be immune from the health effects of bad eating as you get older. This is true whether or not you get fat later on. You can be thin and unhealthy; you can destroy a lot of things by ingesting a chemical cuisine in the place of real food.

While I don’t disagree that some foods are more nutritious and less processed than others, I would argue that—particularly for individuals with eating disorders—a hyper-focus on healthy eating, while seemingly lauded behavior, can actually be counter productive for mental health.

It is true that having anorexia nervosa as a child does not make one immune to bad eating habits later on. In theory, anyway. However, research suggests that bad eating habits are largely unlikely. In a small one-year follow-up study, Nova et al. (2011) showed that recovered AN patients tended to return to eating patterns exhibited at admission—reducing overall caloric as well as carbohydrate and fat intakes compared to immediately post-treatment. In a similar study, Delluva et al. (2011, open access) found that “after recovery, women with histories of AN focus on health benefits of foods more than non eating disordered peers, although overall energy intake did not differ between the groups.”

They write,

In the current study, recovered women did indicate a higher preference for food choice selection based on health benefits compared with control women. Selecting food items based on perceived health benefits could result in lower consumption of unhealthy, unnecessary components of food items (i.e., trans fat and added sugars). Higher importance of food selection based on health benefits in recovered women might serve as an indication that individuals who are able to recover from AN develop healthy eating and lifestyle habits. . .

Others, including Sysko et al. (2005) and Windauer et al. (1993), showed similar findings.

Getting Fat from Eating Junk?

As I read Dr. O’Toole’s posts, I was struck by her apparent fear of patients going above a “healthy weight”, or, in her words, “getting fat”. Consequently, Kartini patients are restricted from hyper-palatable—i.e., “high calorie, high fat, sweet dessert” for at least the first year. Kartini is one of the only ED treatment centers that do not allow its patients eat “junk” while in treatment. In support of this stance, Dr. O’Toole references Ancel Keys’ Minnesota Semi Starvation Study (MSSS): The main points from the study that she highlights involve the consequences of “ad-lib” refeeding with access to calorie dense, sweet, high-fat foods, including:

- Binging and resultant weight gain

- Lack of self-control around these types of “junk” foods

- Gaining past an (arguably arbitrary) “goal weight”

The first and most important point I’d like to address is that the participants in the MSSS did not have eating disorders. They were healthy, young men with no psychiatric history. So, no matter how scientifically accurate and significant the information from the study may be, it should not be interpreted as necessarily reflective of what occurs during eating disorder treatment and recovery. Eating disorders are mental illnesses with biological and environmental causes and thus results from a controlled, scientific study of healthy men who were deprived of calories do not necessarily apply.

From my own experience with dozens of treatment providers in different centers, I have always been provided with a meal plan incorporating challenging “junk food” along with more nutrient-dense and healthy options. I was never re-fed on an “ad-lib” free-for-all basis, like participants in Keys’ were, nor was I restricted from all junk food. Both seem black-and-white to me, and neither present a model of healthy and flexible eating. Why should nutritional rehabilitation be all-or-nothing in terms of these calorie dense, sweet, high-fat foods? And a perhaps more important question: how can eating disorder patients be expected to magically be okay with “normal” eating, particularly in social settings that will, inevitably, include cupcakes, chips, and soda, if they have not ever been exposed to such foods for an entire year in treatment?

Applying Moral Standards To Food

I also question the moral and ethical judgments that are attached to “healthy” vs. “junk” food, and the implication that allowing children to eat “junk food” is akin to offering them cigarettes.

Throughout various treatment centers, I have experienced first-hand different approaches to refeeding. A particular program I was in sang the mantras “everything in moderation” and “variety is the spice of life” – we would have approximate servings of anything from tacos to salad to ice cream pie. Another hospital seemed mostly concerned about caloric intake (so much that every food item was precisely served and calculated down to the ½ exchange) and we could generally eat whatever we wanted, within reason, so long as we finished exactly at our required calorie level.

Existing Guidelines on Refeeding During Eating Disorders Treatment

In researching existing nutritional guidelines, I found that there is shockingly little nutritional information regarding the treatment EDs. I searched multiple databases and while there were many suggestions on how much patients should eat, I could hardly find any guidance on what they should be eating.

One article that I did find helpful studied psychological affect (i.e., feelings, attitudes) towards food and weight stimuli in three groups: patients with acute AN, patients recovered from AN, and healthy controls with no AN history (Spring & Bulik, 2014). In this study, participants from each group were shown a variety of high-calorie, low-calorie, thinness-related, and fat-related images, amongst others. Their reactions to these images were measured implicitly and explicitly.

As hypothesized, both implicit and explicit affect regarding high-calorie food stimuli was statistically significantly different between the acute AN group and the control group, and between the acute AN group and the recovered group. In both cases, the acute AN group displayed a much more negative affect. However, there were no statistically significant differences between any of the three groups regarding low-calorie food stimuli. This indicates that, contrary to previous beliefs, AN patients do not display negative affect towards all foods, but only high-calorie foods (Spring& Bulik, 2014).

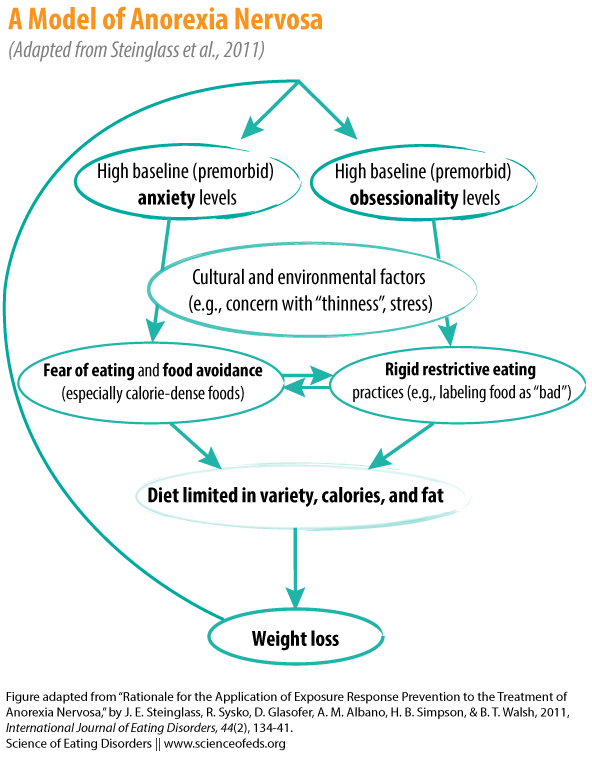

So what does this mean? Spring and Bulik argue that AN may be “driven more by a desire to avoid high-calorie foods (possibly due to fear of fat) than by a desire to consume low-calorie foods”. Elaborating on this, Steinglass et al. (2011, open access) provide an anxiety-centered model of AN:

Steinglass et al. (2011) argue,

AN can be conceptualized as traits of anxiety and obsessionality that result in a combination of fearful avoidance of calorie dense foods, irrational beliefs surrounding eating, and ritualized behaviors that manage the distress around eating. These psychological and behavioral features are present even after successful treatment aimed at restoring weight to within the normal range (Attia et al., 1998) and may be characterized as fear and avoidance behaviors, which could increase vulnerability to persistence of the disorder and relapse.

Setting Priorities in Eating Disorder Treatment

In their article, Spring and Bulik recommend that treatment should help patients reduce negative reactions to high-calorie (junk, hyper-palatable, etc.) food through exposure therapy. They also suggest that recovery may be associated with a decrease in negative affect reactions towards high-calorie foods, which cannot be done by avoiding food:

Treatments may benefit from focusing on reducing negative reactions to high-calorie foods through exposure therapy. Indeed, there was a large difference between implicit affect to high-calorie foods in the patient and recovered groups.

While Dr. O’Toole does not advocate for eliminating high-calorie foods—just so-called “junk foods,” arguably, eliminating negative reactions toward all foods, including “hyperpalatable” or “junk” foods is also an equally worthwhile goal. Indeed, the cognitive behavioural model of eating disorders posits that binge eating occurs as a result of the inability to maintain rigid dietary rules. Consequently, eliminating the rigid and inflexible dietary rules should, in the long run, decrease binge eating–especially when the binge eating is triggered by a sense of failure to maintain the rigid rules (for example, eating a piece of a forbidden food leading to a sense of “failure” that precipitates a binge.)

Recently, Joanna Steinglass and colleagues have published a few papers developing a treatment intervention, Exposure and Response Prevention for AN (AN-EXRP), targeting precisely these eating-related anxieties (see here and here). They argue that, particularly given the fact that “eating patterns prior to discharge are related to such individuals’ ability to maintain longer-term health” (Schebendach et al., 2012 (open access); Schebendach et al., 2008), it is important to engage “patients in the task of confronting, rather than avoiding, fears” so that they can “experiencing decreasing anxiety over time”:

AN-EXRP sessions emphasize the importance of intensifying and experiencing eating-related anxiety rather than avoiding it, and may involve maneuvers to highlight such anxiety (e.g., a session might incorporate holding a greasy food for a prolonged amount of time). These techniques allow the therapist (in collaboration with the patient) to enhance eating related anxiety and provide prolonged exposure to the situation such that the patient learns experientially that anxiety dissipates.

Personally, I believe that being encouraged, and at times, forced to eat chips and drink soda was an essential part of my treatment. I also wholeheartedly believe that the danger of continuing to suffer from an eating disorder far outweighs the evils of processed food (no pun intended). If the choices are between severe restriction or frequent binge/purge episodes and Cheetos, I’ll take the tasty little cheese bites any day.

What do you think, and what are your opinions? Have you ever experienced being presented with “junk food” in treatment, and if so, what was that like for you and how did it affect your treatment? Or, if you are a treatment professional, what types of nutritional guidelines do you/your treatment center follow? Please share your thoughts; I’d love to hear them!

Tetyana’s note: In the next post, Liz will evaluate the animal studies on dietary restriction and binge eating that Dr. O’Toole cited in the comments to the post in support of Kartini Clinic’s guidelines.

References

Spring, V.L., & Bulik, C.M. (2014). Implicit and explicit affect toward food and weight stimuli in anorexia nervosa. Eating Behaviors, 15 (1), 91-4 PMID: 24411758

Steinglass, J.E., Sysko, R., Glasofer, D., Albano, A.M., Simpson, H.B., & Walsh, B.T. (2011). Rationale for the application of exposure and response prevention to the treatment of anorexia nervosa. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44 (2), 134-41 PMID: 20127936

Oh boy.

First, before I formally comment, I need to state my treatment did not include hospitalization or any in-patient treatment. It was through psychotherapy and later a nutritionist with a specialization in eating disorders that has afforded me to recover up to this point. My weight was low enough to be dangerous for me, but not alarming enough for the “anorexia” diagnosis, so rather I was diagnosed with EDNOS/OSFED. Therefore, refeeding was necessary but not seen as urgent as in some other cases.

That said, I personally was told to eat whatever the hell I wanted when I started therapy. It was scary at first, but then I did and yes – I ate a whole lot of it. In fact, I probably had a few episodes through recovery where I binged or ate more than what my body wanted me to. I HAD TO DO THIS TO RECOVER. I had to reintroduce all the foods into my diet until my body became used to it, even if it was in large quantities And yes it caused weight gain and yes it caused fear..all the time. That said, I learned through this that when I don’t restrict “junk food”, not only do I not overeat it, but I crave it less. I keep saying in my recovery that I crave carrots and carrot cake probably equally now. This is biology – my body can successfully tell me what it needs, and sometimes that is sweets.

As of last year, health wise, my sugar, cholesterol and other important counts were where they need to be. Therefore, eating junk AND healthy food in combination (i.e. moderate, healthy eating) has not adversely affected my health yet. Will it someday? Perhaps. I will address it then, appropriately and mindfully.

On thing my therapist said once is that all food as certain ingredients but hopefully all food has the same ingredient – and that is enjoyment. If it’s not enjoyable, it’s less nourishing for us in many ways.

I can see how severely underweight patients may need to wait until downing chips and soda for medical reasons. Maybe it will make them sick, I don’t know. If so, sure, that makes sense. But to restrict any foods as part of recovery is defeating the whole purpose.

Also? Orthorexia. Shit’s real.

Thanks for sharing your experiences, Jill.

“I HAD TO DO THIS TO RECOVER. I had to reintroduce all the foods into my diet…yes it caused weight gain and yes it caused fear”

I definitely agree with you that addressing food fears is an essential element of treatment and recovery…perhaps even one of the most important ones. And of course it will cause distress, in some cases related to weight gain, but treatment should help patients decrease these anxieties over time (e.g., AN-EXRP by Steinglass et al.). If you ignore it, fear won’t go away on it’s own.

I definitely have similar experiences to you today, where I crave both fruit and ice cream, ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’. It’s pretty awesome to be able to feel those cravings and honor them without strings of guilt or judgement attached.

Regarding orthorexia – Andrea wrote a really interesting post looking at the lines between healthy eating and orthorexia. Definitely take a look if you’re interested!

I am a 53 year old woman with a 44 year history of ED, including AN,BN, orthorexia and anorexia athletica. I have been in recovery for just over a year, and am following the MinnieMaud method. My whole life with ED has been spent worrying and panicking about food intake, types of food, and the usual terror about weight gain. By the time I started recovery, I was on an extremely rigid, narrow food plan. So the MM approach that takes away ALL judgment regarding food as to ‘good or bad’ has been incredibly helpful to me. A plan that limited or forbade/restricted any food types would have affected me in a similar way to formal restriction, because of the way my anxiety would wrap itself around the ‘rules’ and turn them into restrictive behaviors. I went from eating mainly junk food at the start, to eating pretty standard home cooked and prepared meals by now, and there is NO FOOD I am scared of and NO FOOD that I consider to be ‘bad’ or unhealthy. The ability to freely eat whatever I feel like at any time has NOT led to me binging myself into a coma, or into morbid obesity as some might predict, but rather back to a standard, average body size and weight. It has also reduced my previous 44 year history of panicking about ‘what to eat and what not to eat’, which has seen me rocket from extreme plan to an alternative extreme plan, ad infinitum. I have a balanced diet, functional bowels, excellent skin, solid deep sleep, strong nails, and dramatically reduced cellulite. My blood results are normal. My mental state is clear, balanced, stable and peaceful – because the main cause – my food fear and obsession – has dissipated. Gwyneth Olten on youreatopia accurately predicts this outcome when she speaks of the hierarchy of foods in recovery: 1. highly processed foods; 2. processed foods; 3. some raw foods – and also that as one becomes weight restored and energy balanced, ones tastes will naturally veer towards a more balanced (in terms of current beliefs about a healthy diet) order 1. processed foods; 2. raw foods; 3. some incidental highly processed foods. http://www.youreatopia.com/blog/2012/12/21/food-family-and-fear.html

Taking the brakes off and allowing free choice with no judgement allows the person in recovery to reduce their fear of food – which ultimately is the root issue needing to be addressed. Practitioners treating people with ED need to practice a form of triage, in that the primary goal is to get the person out of immediate danger, and then to restore weight and energy balance. To restrict food, any food, is counterproductive to that goal – I see many people seeking to recover who are still locked into a state of fear because their therapist or other health professional has warned them not to eat some foods, or to drastically limit their intake of such – this reactivates the drive to restrict and sabotages the recovery. The people that I know who have made it into remission and stayed there for a number of years are those who did not restrict calorie or junk food intake, rather following the ‘free choice, restriction free’ model. The people that I know of who have struggled over and again with relapse are almost always those who are only allowing themselves access to a set number of calories (and then stopping) and/or limiting their ‘junk food’ (or foods they deem to be ‘bad’) intake.

I literally eat anything I feel like – and that often means that I say no to some foods due to a complete lack of desire. Once they were no longer forbidden to me, they lost their mystique, and assumed an ordinary status. I find my taste in food is for nutrient dense prepared food – basic home cooking – and that I have little or no desire for junk – but when I DO want it, I eat it freely, to satiation, and without anxiety.

The polar opposite of a restrictive eating disorder is restriction-free eating. And the only way to achieve that goal is to create an environment and a set of behaviours that mean the amygdala no loner perceives any food as threatening. Again, therapists need to take the lead in driving such a change – and one of the primary things they need to do is to stop imposing their own fears, or healthy food beliefs, on their clients and instead encourage a return to a state of homeostasis at ones optimal set-point – the point at which the body will manage and monitor energy intake without intervention, in order to keep the body in that stable condition.

Hi Ruth, thanks for such an insightful comment! Congratulations on coming so far in your recovery. I personally have not used the MinnieMaud Method, but have heard good things about it. I think when you said “A plan that limited or forbade/restricted any food types would have affected me in a similar way to formal restriction, because of the way my anxiety would wrap itself around the ‘rules’ and turn them into restrictive behaviors,” you really hit the nail on the head. Lots of people are pointing out that restricting certain ‘junk foods’ during treatment could be counterproductive, e.g., leading to a more restrictive eating disorder or orthorexia.

A helpful analogy for me is a patient with severe OCD. If he engaged in obsessive and compulsive hand washing, he might eventually be asked to get his hands dirty and not wash them for X period of time…not with the goal or outcome of him rolling around in dirt and never showering, but being able to live a life where he can use public transportation or go to the mall and not panic.

I also agree that treatment professionals should help their patients achieve restriction-free eating. You make a great point about practicing a type of triage, and to my knowledge, the steps you mentioned are followed in most treatment centers. It’s the ways in which weight and energy restoration occurs after immediate danger has passed that everyone seems to have varying opinions about.

The primary trigger for R.E.D’s is restriction. So it seems to logically follow that any treatment plan, and long term maintenance plan, needs to factor in that reality. The increasingly, and so often deadly, response of the ED brain to the presence of neuropeptide-y mean that all with ED need to be retrained so as to avoid any further restriction. They also need (as do any practitioners involved in their care) to become well acquainted with set-point theory, and with current peer-reviewed research into the erroneous, all encompassing assumption that higher body fat levels, overweight, and even obesity are automatically a causal factor in some health conditions. This involves an understanding of what actually constitutes a ‘healthy’ BMI, and the abandoning of making sweeping assumptions about what going above that BMI range means healthwise. I have observed that some people involved in the care of people on the R.E.D scale are themselves actively restricting, and that this directly affects the advice they give their clients. It is tantamount to someone with an active drug or alcohol addiction advising those in recovery from such things in a way that actually supports them continuing their addictive behaviours. In some cases, R.E.D clients are told firmly to restrict food groups, or to keep their calories below a certain level as a means of keeping their bodies within a BMI range that is socially acceptable, but that may have no bearing on their optimal set point.

ED is the leading cause of death of young women aged 15 – 24. And it is a primary cause of a wide range of health problems that dog people into middle age and beyond.

The only way to stay in remission is to remain restriction free – and thus stop the cycle.

There is a case for the interrogation of, at the deepest level, the way that the ED treatment world at large understands this most basic fact, and the way in which that translates to its treatment. I see women who have been in treatment for many years still actively restricting, with the blessing of their therapists, who are perhaps unwittingly and unintentionally colluding with and enabling their clients to carry on restricting. The damage to heart, kidney, bone, and myelin sheathing to name a few being done while these people are supposedly in therapy, and no doubt feeling reassured that this is the case. needs to be admitted – and of course, curtailed.

The reality of having a higher BMI or body fat level than that we are told is ‘healthy’ is that unless there is a disease state present, it is a predictor of a long and healthy life, with a better health outcome when disease does strike.

It also needs to be said that by focusing on junk food vs nominally healthy food, our attention is being drawn away from the actual calorie level at which people need to remain in order to reach a robust remission – those who ‘recover’ to a BMI in the ‘low healthy’ range that many therapists seem to feel comfortable with, and who then restrict in order to maintain that weight, are almost certain to relapse. The ongoing and unrelenting orthorexic panic about different food groups and types (which is often a matter of fashionable trend as promoted by marketers of ‘health products) has created a minefield when it comes to issues of weight and health. It is generally better to be at a stable weight, albeit higher than that healthy BMI we are told about, than a cortisol-heavy catabolic state that cycles of harsh calorific restriction and its best friend, intense exercise bring us to. When we focus on junk food as if it were a medieval devil, we lose sight of the bigger, and deadlier picture.

Will eating junk food only, kill you? Possibly. Will a lifestyle of harsh restriction and recovery attempts interpersed with periods of eating at a very high level of calories kill you? Even MORE possibly. Will living a lifestyle without restriction, allowing your body to find its own set point, and resting and nourishing it appropriately, with free access to a wide range of foods, including ‘junk’ kill you? Of all three, the latter is fundamentally safer, and offers a higher level of life satisfaction, whereas the second is the most inherently dangerous, and of the three is – to me – the least desirable, mainly because of how horrendously it has affected my body and life.

I agree that restriction is a trigger for restrictive eating disorders, however I don’t know that it can be generalized as the primary trigger across the board for everyone. If you are referring to Dr. O’Toole’s post, from my understanding, she is more concerned about the unhealthiness and health consequences of junk food than restricting caloric intake to keep patients below their set point. I think you make a good point in not letting questions of health draw our attention away from the bigger picture. Most of the research I’ve found regarding nutritional guidance in the treatment of EDs is calorie-based and does emphasize the importance of adequate intake, which as you said, is very important. I’m sorry that you’ve observed clinicians enabling or encouraging their clients to restrict food groups or calories.

I really appreciated your last point about the three scenarios, and think it’s important to recognize everyone’s unique situations and prioritize. Eating junk food in treatment and maintaining recovery is ultimately a much better option than continuing to suffer from an eating disorder.

I need to quote from Gwyneth Olten here: ” Neuropeptide Y and Hyperactivity

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is “considered the most potent orexigenic neuropeptide known” [EJM Achterberg, 2009]. Essentially the presence of NPY generates increased appetite, hunger and feeding (orexigenesis). When energy deprived, the levels of NPY increase in our central nervous system.

The investigation of NPY in anorexic and bulimic patients is one of several areas that Walter Kaye, a leading researcher in the field of eating disorders, has covered in numerous published papers. While it does appear that NPY and other central nervous system neuropeptides are altered in both anorexic and bulimic patients when compared to healthy controls, Kaye and colleagues have determined that the alterations are due to restriction and not causing restrictive behaviors [UF Bailer, WH Kaye, 2003].

Increased NPY levels in semi-starved animals and non-ED humans lead to lowered NEAT and increased food intake. For reasons not yet known, increased NPY in those with restrictive eating disorders leads to increased activity and decreased food intake [R Negård et al., 2007; EJM Achterberg, 2009].

In other words, NPY levels increase for all of us if we are semi-starved, but for those with a genetic predisposition for a restrictive eating disorder, the result is increased activity. In fact, the drive to be active decreases as an eating disordered individual re-feeds [UF Bailer, WH Kaye, 2003].

The most compelling theory as to why this altered NPY response may be present in those with restrictive eating disorders is the evolutionary benefits afforded a group of humans if some individuals are driven to forage for food in times of scarcity [S Guisinger, 2003].”

http://www.youreatopia.com/blog/2013/2/26/insidious-activity.html

That explains beautifully why restriction is one of the riskiest behaviours, especially for those who have the genetic predisposition to go on to develop a full blown ED. You will note that the quote comes from a blog post on activity in relation to restriction, which offers a primary argument against exercising while in recovery.

In short, anything that maintains or creates a state of restriction triggers this neurobiological response, which is the basis of the most deadly and hard to treat EDs that plague us.

I am glad you enjoyed that trio of options – for sure the pathway of restriction and intense activity is scattered with the corpses of many people who truly believed that this was the healthy option, while also playing host to a myriad of people lost in the hell of ED in its many forms. Becoming comfortably fat, and balanced, and calm seems a reasonable choice in light of the heavy cost to life and sanity offered by restriction.

That’s very interesting – I actually hadn’t heard much about NPY before, so thanks for letting me know! I will definitely continue to look into it and read more on my own. Also, thanks for putting so much time into your comments. I appreciate all your thorough responses!

Ha – thank you. I have to point you in the direction of the blog posts at http://www.youreatopia.com/ – because that is the source of much of my knowledge – Gwyneth has a plethora of research freely available, and her site is a source of the richest CBT I have ever encountered. I encourage you to dip into the blog posts – I guarantee the breadth of your knowledge will widen almost immediately. This is a very well informed and responsive community and Gwyneth’s work deserves to be better known.

I was diagnosed with AN R type years ago. I never had to undego hospitalization or inpatient treatment, I went to a psychyatrist and a nutritionist myself when I realized I needed help and was motivated to get better. My nutritionist taught me how to regain and maintain weight by eating a healthy diet. She never counseled me to avoid junk food at all costs, and said occasional reasonable portions are okay. But she never, ever tried to “make me” eat those foods. I think that if she had, I would have rebelled, and never followed her advice. I wanted to get my health and vitality back. Being force-fed junk would have set my recovery back.

Hi Suzanne, thanks for sharing your experience. I can definitely empathize with your thinking, and self motivation and desire to ‘get better’ are important factors in treatment outcome, albeit not the only factors. There’s a lot of research describing scenarios where patients are not willing or able to make wise decisions for themselves, and that these decisions should be made for them for the time being (this is a key feature of the first stage of Maudsley Family-Based Treatment). Of course this leads to the question of whether encouraging or forcing junk food is wise – and I think that in the context of an eating disorder, it is far better, wiser, and healthier for a patient to be introduced to junk food in moderation, rather than risk them continuing to suffer from the eating disorder.

I’m unclear how the Minnesota study proves that “junk food” should be avoided in tx – in fact, I think it proves we shouldn’t restrict access to any foods – particularly if we’re trying to help people recover. It’s precisely the restriction of these foods that causes the lack of self-control around them when finally exposed to them. When I hear about providers restricting patient access to certain types of food, I think that they have bought into the thin ideal/weight stigma and am frustrated that these are some of the same beliefs that fuel the disorders themselves. Let’s align with flexibility and recovery, not with eating disorders.

Thanks for your comment, Stacey! I think that when Dr. O’Toole refers to the Minnesota Semi Starvation Study as an argument against junk food in treatment, she is focussing on the result of “ad lib” or free-for-all refeeding in which the patients are given unlimited access to whatever high-calorie hyper-palatable food they desire, resulting in “getting fat”. From my understanding, Dr. O’Toole wants to avoid the negative consequences associated with this type of refeeding (e.g., binging, uncontrollable weight gain). However, as I mentioned in my post, I believe that the MSSS should be interpreted and applied to ED treatment with caution – the participants in the MSSS were otherwise healthy young men with no psychiatric histories, and no one is making a case for free-for-all refeeding in ED treatment. Appropriate meal planning and nutritional guidance is usually given by a dietician, which as you said, should include flexibility with all types of food. You make a great point that in some cases it is the restriction of foods that leads to lack of self-control when finally allowed to eat them, and that when providers restrict ‘unhealthy’ foods they are fueling the disorder. I agree with you!

The question of ‘binging’ in R.E.D recovery needs to be rethought in current treatment practice – as does the over concern about people getting ‘too fat’ if they are allowed to eat without restraint. There is an ongoing pressure to apply restriction either on calorie levels or on the types of foods ‘allowed’. Two things: to term the act of taking in a high level of calories, or eating a lot of ‘junk food’ ‘binging’, in the context of a severe and life-threatening calorie deficit, is inaccurate. There is a need to allow the body to restore that deficit as quickly as is possible (once the risk period for experiencing refeeding syndrome has passed), and also to see ghrelin and leptin levels restored to normal – which can take up to 6 months or more. Also, ‘junk food’, as in highly processed food that is calorie dense and easily digested is a very efficient means of someone reaching their calorie minimums without suffering undue digestive distress. Restriction causes the gut to lose vast quantities of the necessary flora and enzymes vital to digestion. It can be very difficult, if not impossible for the body to effectively break food down into its various components with a gut so compromised. If you look at the foods the World Food Program http://www.wfp.org/nutrition/special-nutritional-products uses when responding to situations of famine or malnourishment, you will not find a lean chicken breast, salad or egg whites among them. Instead they are highly processed calorie dense foods. It has been proven that people who are starving (and lets face it, that is often the case with people who are on the RED scale) are unable to digest more complex foods, so it is necessary to build the gut back up to full capacity by starting with these simple highly processed foods that need very little work to break down in the gut. Gut flora alone can take some months to return to optimal levels – and this means the person’s ability to access the nutrients from the food is compromised. To put it baldly, people whose calorie deficit has been so low and who have sustained so much damage often die when fed more complex foods – they simply lack the ability to break them down and access the nutrients, and more crucially, the actual calories so essential for sustaining life. That is the reason, if you care to investigate further, that these highly processed foods have been developed; to deliver maximum levels of fat and carbohydrate and protein in the most easily digested form available. You will note that the Plumpy variety has 34 grms of fat per 100 grams. Not unlike ‘junk food’. But it is effective in this specific context, as is junk food in the specific context of ED recovery.

Because restriction itself is key to the triggering of ED behaviours due to its effect on the brain, the current practice of restricting once a certain arbitrary weight or BMI is reached, and also certain food groups are restricted if not banned altogether, is a main reason for people relapsing so often – no doubt you know of people who are in and out of IP settings – they are refed to BMI 18 – 20ish, released, quickly relapsing and being readmitted. The cost to the body in terms of damage to heart, myelin, and bone density, as well as other organ damage, is incredibly high in these cases, with the level of restriction driven stress being immense and sometimes unrelenting. It has to be asked – what will damage a person more: these ongoing bouts with severe restriction and a constant battle to keep ones weight up, or being allowed to regain weight and perhaps overshoot their own set point to where they are at a higher BMI and body fat level than that ‘healthy range’ current fitness and health trends would like us to accept? If you have had dealings with people who have had AN for many years, who have added enough calories to stop them dying, but are still actively restricting you will no doubt know of the damage that has crept upon them cumulatively – including permanent and irreversible nerve damage, and heart damage, bone density loss, and muscle atrophy, leading to a severely restricted lifestyle, and immense emotional distress. Can we call this recovery in truth? What would be the difference between the same person being allowed access to unlimited calories and food groups, gaining to a higher level than their set point, sometimes well above, and allowing their eating to ‘normalise’ in the course of time, and their body to taper and weight to redistribute, leaving them able to function normally, and with those body parts mentioned having been repaired and replenished to optimal levels – or certainly higher levels than the person who is still restricting but to a lesser degree? Current research suggests that this in fact is one of the strongest indicators that someone will not readily relapse.

Myelin sheathing, particularly in those who restricted from age 16-25 in the frontal lobes of the brain, is always compromised – it is only possible to restore it with high levels of dietary fat over a consistently long period. To focus on whether someone has a fat butt or a podgy gut is terribly shortsighted, given the crucial nature of myelin and the role it plays within the body.

Someone who goes into an IP setting for a number of weeks, or a person who is recovering in the outside world for several months, whose calorie intake is restricted once they reach a certain weight or BMI, is almost inevitably going to relapse, or their ED will morph into another form of the disorder – i.e. AN to BP, or to orthorexia or athletica – and it is not unusual to see people with a very long history of ED having shifted from one form to another many times in the course of their life, because the fundamental issue of living without restriction, and is accompanying effect on the brain causing it to continue to drive restrictive behaviours, is simply not addressed. I am talking people with 40 and 50 year histories of ED, whose history is a litany of damage control and who have never been able to free themselves and their bodies from the crippling effects of ED. Their life expectancy is lower as a result. And if you ask them, so are their levels of life satisfaction. Many say that they were unable to live ‘normal lives.’ Those that I know personally ALL shy away from ‘junk food’ and all still live with restriction, albeit less severe than it once was. What would be the outcome if they had been allowed and encouraged to recover freely, without any restriction, and with CBT or similar training to overcome the fear of food itself (as in the amygdala misinterpreting food as threat). Current practice that is restrictive in ways as mentioned above can, and does, reinforce that fear response, locking people in to the circle of restriction. Think of the young women you know that have battled AN for years and years. Is being allowed to restore their weight rapidly by eating primarily highly processed foods in the intitial few months going to cause more damage than restricting their calorie intake and food groups? We all know the answer to that. AN kills, without mercy. They are not getting the form of treatment that they require to achieve a robust remission.

If the worst that could happen to someone living without restriction was they they get fat, how bad is it really? What will happen to people who have followed this style of recovery and have focused solely on the restriction itself, without playing what Gywneth Olwyn calls ‘whack a mole’ with fears re body ft levels. if you read the section of youreatopia you will see that plenty of people have done this, and have achieved long term remission, and have also returned in the most case to an average BMI and weight. Their remission often involves physical issues being resolved, and some health conditions reversed. More importantly, they understand the way that their brain responds to restriction, and they are cognizant of set point theory, and are thus able and competent to eat to hunger cues, with no fear foods, no ‘bad foods’ and with no major fluctuations in weight and size.

We need to ask if our (often ED driven0 fears of ‘body fat’ and ‘junk food’ are doing a damn thing for those young people dying in hospital beds all over the world after having being encouraged to eat ‘clean food’ and to ‘not go overboard on junk food’ and to ‘keep their calories below a certain level for fear of getting fat’ each time they entered IP treatment or talked to their ED therapist (who often has no nutrition qualifications). We need to see the real issue here – and that is the role that restriction plays in these deaths, and to be prepared to attack it from a very different angle in the future. ‘Junk food’ has saved, and will continue to save, many lives. Calorie restriction or food group restriction for those who have ED will take many many more unless we learn to change our viewpoint.

I agree that patients should not be restricted at a certain calorie level or banned from certain foods once weight restored. I’m confused, though, on how you are seeing that current ED treatment encourages these practices. I cannot speak about every single treatment center, but from my knowledge, most do encourage patients to practice intuitive and restriction-free eating (usually after they are stable and ready to move away from a meal plan). While the issues you discussed (e.g., de-mylenation, diagnostic crossover, quality of life) are all serious problems, I think it’s important to be careful with over-generalization and extrapolation.

Thanks for pointing that out. My statement about current practice was referring to all that restrict, or encourage a form of restriction (be it actual calories or food groups/types) once the patient reaches a certain weight or BMI, or those that restrict if their perception is that the patient is ‘gaining too fast’ or ‘making bad food choices’ – both of these reinforce the underlying perceptions of body fat and certain foods as harmful, and may – and often do – trigger relapse. Of all the people know who have attmpted recovery with a team who set an arbitrary healthy weight/BMI or who restrict food in any way, there is not one who has failed to relapse = some many times, including people who have been in ‘treatment’ for five or more years without ever coming close to remission. As long as they are being validated in relation to restriction, they will be unable to achieve remission – because the restriction will hold them back each time. And yes, many treatment plans encourage intuitive eating, but many of them also have an upper limit on calories and on weight gain – things i believe are counterproductive in the long term.

Hi Ruth,

I like the spirit behind your comment, and I agree with most of what you say. I think there is one danger in becoming significantly overweight (according to BMI) for people recovering from anorexia/bulimia, and that is, being significantly overweight may well trigger a relapse into ED behaviors.

There is a problem with anorexics starting to binge as they begin to recover, and it seems professionals have not yet figured out what the best approach is for handling this. My doctor, an ED specialist, told me if I started bingeing, she would, “put me on a diet,” or alternately, “tie my hands behind my back.” She later said, “I don’t know what we’d do,” which is more honest. The reason so many anorexics develop bulimia is that they start to binge, and freak out. Of course, if they continue to purge, they will never let their bodies sort things out.Maybe it is inevitable that people who restrict for long periods of time will binge (or overeat), but it’s sure as hell not easy to go through. I’m skeptical of this approach of avoiding highly processed foods for one year, but if they can show that patients are less likely to develop a binging problem, I’d reconsider. A lot of people don’t realize this, but binging itself is dangerous; I know of a woman who burst who stomach from binging. She had developed bulimia after being hospitalized for anorexia.

To me, the problem is viewing the bingeing as a problem in these cases. It is our body’s normal response to a prolonged period of restriction. Of course it is difficult to get through, but pathologizing it or calling it a “problem” as opposed to “this is a normal thing that most people in recovery from restrictive EDs go through” just makes it worse.

Sarah, the underlying cause for ED is brain-based; the amygdala misidentifies food as a threat, and the anxiety can become fixated upon the body and weight gain. Weight gain, or perceived weight gain, is one of the biggest triggers for most of us – and until THAT is changed by rigorous brain-retraining, as termed by Gwyneth Olwyn of youreatopia, the ED will be in an active state, no matter what weight your body rests at. The fear of excess weight gain, or of eating too much, perpetuates ED behaviours.

Your clinician’s approach is actively reinforcing your fear of ‘overeating, weight gain, and being overweight’. The approach itself is flawed, because scholarly research clearly shows that most people in recovery will overshoot their eventual end weight, and that they will accumulate extra visceral fat in the early stages of recovery; the same research shows that this extra fat will dissipate in time, without restriction.

Other good quality research, as well as a growing body of anecdotal evidence, indicates that after a period of extreme hunger, with the person eating a very high level of calories for weeks or months on end, the eating will even out and the person will NATURALLY return to a normal calorie intake in line with what other people of a similar build and age eat without restriction. Overeating, or eating calories in excess to the day’s needs, is a normal response to starvation. The body will demand excess calories until energy balance is achieved, and until the massive deficit has been made up for. The term binging – as Tatyana says – pathologises this survival strategy. To reinforce your already existing fear of your body’s reaction is to short change you. Your body is capable of managing your food intake, and of balancing that intake out in time, as long as it is given the chance to do so.

Until a person with ED retrains their brain to lose its fear of food, weight gain, and a higher BMI than might be socially acceptable, they will not move into a remitted state.

Your clinician needs to consider educating you about ‘set-point’, your inherited, genetically pre-set weight range that your body will aim to get you to and keep you at for your entire life, and that has been hijacked by ED. Research shows that eating without restriction, stopping the use of exercise to lose or limit weight gain, and undergoing CBT or similar to retrain the brain to see food as an ally and friend, as opposed to a threat, the body will gradually return to the set-point range without intervention.

She also needs to teach you about the relationship between health and weight – instead of insisting that you stay at an arbitrarily chosen weight and size. The healthiest state for any of us is to be at the set-point we have inherited, without restricting in any way, and to live in line with our physical and emotional needs. A life spent restricting in order to meet societal standards of physical appearance is a life fraught with anxiety, unhappiness, and often – despair.

The vast majority of people who recover in a restriction free manner will NOT suffer a burst stomach from overeating. That is a very rare occurrence. And those who recover and find that they have a higher set-point than they prefer do not suffer any long lasting harm from this. However, the risk to anyone with an active ED is that their condition will take their life; if it doesn’t take their life, it will rob them of health, happiness, and many of the opportunities that non-restricting people will enjoy – having children,enjoying long term intimate relationships, and worthwhile productive careers.

Your body is your ally, your friend. It does not need controlling or punishing. You do not consciously control your breathing or perspiration, your heart, liver or kidney function. Your brain, gut, nervous system, endocrine system, and cardiovascular system all function without your deliberate input. Without ED, people eat, drink, and maintain a stable weight without any conscious restriction, because their bodies are designed to do ALL of these things without interference. A robust remission means that we have re-trained our brain to manage the ED anxiety without restriction, and that we have learned to allow our body to do what it does best – keep us alive, and manage our entire physical function. It also means that we have learned not to fear food, or weight gain, or to see body fat as pathological. And, in the process, most of us will go through periods of extreme hunger and eating, and we will survive, and our eating will even out and normalise on its own, in time.

I don’t see a way to directly reply to your comments, so I’m going to reply here.

Tetyana,

Yeah, I see what you’re saying. The thing is, what if the overeating (binging) really is extreme and disruptive to one’s life? I know people who are able to overcome restriction without going on all-out binges; they may become slightly “overweight” for a bit, and then their weight stablizes at a bit of a lower place. But they don’t go on all-out binges. For another group, the binge eating really is life-disrupting and physically painful. At what point does the binge eating turn into a disorder of it’s own? In cases where purging is regularly used, it’s probably a little clearer.

I do think medical professionals who work with people recovering from AN should be aware of the tendency to overeat and in some cases, binge, and should not be alarmed if the patient becomes overweight for a period of time. In my case, there were other factors besides the AN contributing to the binging I did over a decade ago. I was severely depressed at the time, and going on anti-depressants helped tremendously. Eventually, I even had to start eating meat, and at that point, I felt better and more physically full, and haven’t had a binge since. My prior period of starvation definitely opened up the door to binge eating, but it wasn’t the only reason I did it. I don’t think it’s a contradiction to say I do have every reason to believe I would never have binged if I had not starved

Ruth,

Can I ask what your background is? As in, are you a ED survivor, nutritionist, therapist, etc? I’m curious, as it would help me more understand where you are coming from.

To be clear, these were comments medical doctor who specialized in EDs, said to me as a teenager. I don’t agree with what she said; those aren’t things she could have actually done to help me if I had been binge eating under her care. FWIW, I haven’t been underweight or anything remotely close in 13-14 years.

I notice your focus is on restricting EDs. To imply that binge eating is not a problem for people overcoming anorexia, is to imply, in my opinion, that people with anorexia don’t experience what this site refers to as “diagnostic crossover.” In reality, many people do. I’m wondering if you think BED is not a real and life-disrupting disorder with physical health consequences?

As I said before, I agree with much of the spirit behind your comment. I do think if people recovering from EDs want to be at a weight that is healthy for them and also on the lower end of the healthy spectrum, nutritionists, doctors and therapists, should be able to work with them on how to achieve this in a realistic, self-affirming manner. I don’t think people in ED recovery should be held to a higher standard than the rest of the population in terms of accepting ourselves at any weight. At the same time, I/we should work to change society to obliterate prejudice and stereotypes related to weight.

“Other good quality research, as well as a growing body of anecdotal evidence, indicates that after a period of extreme hunger, with the person eating a very high level of calories for weeks or months on end, the eating will even out and the person will NATURALLY return to a normal calorie intake in line with what other people of a similar build and age eat without restriction. Overeating, or eating calories in excess to the day’s needs, is a normal response to starvation”

I very much agree with what you’re saying happens in starvation situations. But people with AN are already using food to cope with their feelings, and it does happen that they go on to develop another disorder related to using food inappropriately, this time binge eating. (And I am not talking about subjective binges here, but actual, out-and-out binges, that make participating in daily life impossible). To get back to the OP, I think the clinic is trying to find a way to help patients recovering from AN do so without developing a full-fledged binging problem. This makes sense, right, because the goal is to be free from ALL EDs? I would need to see evidence that the program is successful in preventing patients from developing binge eating problems before I could support this approach, and I tend to agree with what others here have said on the blog about it.

Back to your comment… The truth is there is no guarantee that one’s weight will settle down at a natural point and pretty much stay stable. We’re living in a society where lots of our bodies’ systems have been overridden, including from toxins and chemical exposure, and also from medications we take. The reason there are so many people who are overweight and obese, by which I mean, at weights not healthy for *them* is precisely because our bodies’ systems are regularly overridden. Things like the kinds of foods we eat and amount and type of exercise we do can also alter our setpoint. So, it’s really not so simple as just, “eat when hungry, and you’re body will settle out where it needs to be.” I wish it were, but it’s not.

Hi Sarah, I am an academic, a writer, and have a masters degree in the area of psychological trauma, and taught interpersonal communication at a tertiary institution for some years. I was until recently also a dance fitness instructor running boot camps and weight loss challenges, while competing in the same. I am also an ED survivor, in active recovery as we speak, partially from July 2013, and fully from August 2014. I am 54, and from age 9 – 52 cycled through different versions of R.E.D’s – including periods of AN from age 9 – 13, cycling between BN and AN from age 14 – 20. From 20 – 54 I was a restrictive eater, dropping into subclinical AN at certain times of deep stress, and cycling between anorexia athletica, orthorexia into what I now understand to have been periods of remission. I had full blown AN and was in a state of clinical starvation when I commenced recovery in 2013. I run a facebook page dedicated to ED recovery, and write a blog about the same. http://amazonia-love.tumblr.com/

Until I understood the nature of R.E.D’s I believed that I had ‘once been bulimic and anorexic’ and that I had recovered. I also believed that I had ‘gotten my eating under control and managed my eating and my weight, without ever binging again’ once I was no longer actively bulimic. My understanding now is that I have been suffering from an R.E.D since age 9, with my disorder having been in both an active and remitted state at various times.

The shift in my understanding has come about after engaging with scholarly research on this topic, and in particular with first getting a far better understanding of set-point theory, and how weight maintenance works in the non-restricting population; non-restricters maintain weight by metabolic means; the body does it without the need for interference. By contrast, caloric restriction of the human body alters metabolic pathways, and is known to be a contributor to ongoing weight gain. I also have a deeper understanding of the nature of overweight/obesity, and how this relates to health outcomes in the general population.

But by far my most significant understanding of R.E.Ds has come about through reading research into the brain’s response to a calorie deficit, and in particular to to the presence of neuropeptide-y; in the normal non-ED brain this will drive the person to eat. With an ED brain, the drive will be to restrict further, and to move more, and to me it is the root of the R.E.D conundrum. For us, restriction is an anxiolytic, reduces anxiety, and we usually develop a raft of behaviours that sustain restriction in some form, including BN, which is usually a cycle of restriction, extreme hunger and eating, and purging or exercise. You mention BED – and neurobiologically, this is closely linked to all other disorders under that umbrella heading of an R.E.D: “BED is a subcategory of BN; which is, in turn, a subcategory of a restrictive eating disorder; which is, in turn, a subcategory of an anxiety disorder; which is, in turn, a biological propensity for a hyperactive threat identification system in the brain. And the activation of that propensity rests with innumerable environmental inputs and experiences unique to each individual.” (Gwyneth Olwyn 2015)

So I now understand my so called ‘healthy weight maintenance after having recovered from ED’ to be in fact a lifetime pattern of restriction that morphed from one form of the disorder to be the other. And I can see, as was the case with me, that many of us get stuck in the pattern of ongoing restriction because of unrealistic fears of ‘gaining too much weight’, ‘binge eating’ and ‘becoming morbidly obese.’ The science around recovery from starvation shows us that most people will indeed eat voraciously and furiously at some period in their recovery; but it also show that if left unchecked, the eating will even out and normalise in due course.

I can also see, as was the case with me, that fear of gaining too much will mean that many will continue to limit their calorie intake, or food groups, or exercise as a means of maintaining a preferred weight – one that is socially acceptable in most cases, without realising that they are in fact managing anxiety by restriction. Anxiety management is the goal, restriction is the method of choice.

So my focus on recovery shifted from the old ‘whack a mole’ of shifting from one eating/exercise regime to another (and often disguising these as means of improving my health, especially recently), with the restriction and exercise and other behaviours ramping up when life became stressful, to one that deals with re-training my brain to respond to anxiety in a different manner, and eating whatever I want at any given time, in any quantity. My past history of BN means that I am no stranger to extreme hunger or eating, and gaining such a profound cognitive awareness of the anxiety driving my past restriction meant that I am not scared of ‘eating too much’. My appetite has regulated itself, altho at the start I did have specific calorie minimums, but now I hit those, and above, consistently. I did gain a lot of weight, very quickly, but my blood markers are all very good, with the exception of some inflammation, which is likely due to the severity of my restriction in combo with excessively heavy weight lifting and long hours of cardio. I am currently losing weight, both body fat and edema while maintaining a calorie intake of around TW 3000 calories TWE. My fellow recoverees (200 or so on the FB page, and some 100s on the youreatopia site have similar stories to tell.

It appears that most pass through, successfully, a period of extreme hunger, and that giving in to that hunger is crucial to retraining the brain to stop responding to food, the act of eating, or the thought of weight gain with anxiety. It is a very powerful form of ERP (exposure response prevention). Not everyone enjoys this stage, in fact very few, but once it is past, the vast majority settle to a standard diet without needing to restrict.

It is essential to get on top of the anxiety to be able to move into a successful remission. You mention people with AN ‘using food to cope with their feelings,’ – but what the neurobiological science shows is that it is in fact restriction that is anxiolytic. Yes, there are crossovers from AN to BN, but there is ALWAYS an attempt to restrict calories present at some stage, and the extreme eating usually happens in response to a deficit.

As regards obesity and overweight – there is enough evidence in current research to show that it is possible to be healthy and stable altho obese. BMI measurements are wildly inaccurate, and have never been diagnostically sound. They are a statistical tool first and foremost, illustrating the range of weight deviations across the population. The ‘obesity paradox’ (worth researching) shows that health outcomes are usually better for those in the overweight to obese category than those in the lower BMI ranges.

No, there is no guarantee that a person who stops restricting will end up with a body size that is socially acceptable; but set-point theory and related science show that the body is capable of correcting both underweight and overweight (for the inherited set-point) without interference if ideal conditions exist – these include unrestricted access to food along with other lifestyle measures.

Fear of being overweight or obese locks many RED sufferers into a lifetime of misery. My father also had ED – he died in August 2013 after a period of starvation and refeeding sent him into kidney failure, after a lifetime of restriction that closely mirrors mine. He was a normal sized man, without a weight problem, and his ED robbed him of much happiness, and eventually his life. And it meant that we his family lost him too. I am happy to accept that my body may end up overweight or obese at the end of this recovery process. Already the unrelenting anxiety I have battled for as long as I can remember is in remission, and I am beyond grateful for that.

Sarah, I should also have added that the method i chose for my recovery is scientifically sound, and that youreatopia.com is the brainchild of Gwyneth Olwyn, whose unstinting and open research has literally saved lives. The method is known as the Minniemaud Method (MM), and as a starting point combines the research done as a result of the Minnesota Starvation Experiment and the Maudsley Recovery Programme. As an academic, I was impressed with the quality of the references Gwyneth provides, and followed it up with my own research. It is fair to say that my understanding of body fat, obesity, set point, and ‘health’ has changed permanently. Of more importance, I am no longer using restriction to manage anxiety, and THAT alone is worth the journey to this point.

Ruth,

Thanks for sharing a bit about yourself. It helps to know where someone is coming from.

Also,I didn’t mean to pick on you with my original reply to your post. I had been looking to post my thoughts on this topic, and rather than reply to the post, I ended up replying to you.

I did quite a bit of reading on the Eatopia site last night, and as you say, it is really a fantastic resource. I plan to continue perusing the info there.

I am so glad you have found something that works for you at this point in your life. My problem is with insistence that one method is *the* way. I also have problems with some of the claims made on the website; they definitely apply to a subset of the eating disordered population, but the way they are presented is that they are true of everybody. For example, the Gweneth cites research that people with EDs tend to move more (the acronym is NEAT) as they restrict and move less as they eat more. I know this is true of some people with EDs; however, it most definitely was not true of me when I restricted and subsequently gained weight. I also don’t agree with her presentation of BED as being solely caused by restrictive eating. Again, this is definitely true of a subset of the BED population, but I definitely know of people who this is simply not true for. Yes, restricting can and often does reduce anxiety; eating, particularly eating sugar and carbs, causes a mood lift. For some people, eating large amounts of sugary foods is a way to cope with feelings, depression in particular.

In regards to BMI and obesity, I am sadly aware of the flaws of BMI, and the fact that obesity in and of itself does not mean one is unhealthy or destined to type II diabetes. But it’s also true that body weights in the U.S. have been steadily increasing in the last several decades and continue to do so. When we look at other species (non-domesticated ones), we see creatures who are about the same size. I know people who have flown here from abroad, and are shocked by how many really fat people there are here. (And I don’t mean “fat” in a pejorative sense and would never use it as a moral judgement). Our bodies aren’t to blame; the systems have been overridden by our environment.

All this is to say: I have a tendency towards rigid thinking and believing I have found THE solution and must evangelize it to others. And over and over, I have learned the hard way that just because something makes a lot of sense, or I really believe in something, doesn’t mean it will work for me. And if it works for me, it may not work for others, not because they’re “not doing it right,” but because it’s not the right solution for them.

I wish you nothing but the best on this journey of recover.

Hey Sarah, good to hear that you found your way to youreatopia.

What has helped me with regard to the question of obesity/overweight is that regarding recovery as if I were performing triage. The primary issue was to stop restricting and restore weight; the second, and related issue, was to understand the way I have used restriction to manage anxiety, and to particularly understand how the NPY response affects me. The matter of whether I become overweight or obese while this happens is not lifethreatening in any way, whereas I was at risk of a heart attack while restricting.

I don’t consider MM to be *the* way – but rather it is my chosen way of recovering, with me adding other things as I feel the need. Until I understood that I was in fact locked into a restrictive pattern that simply morphed from one mode to the next, I believed that I HAD recovered already. I hear you on rigid thinking; that is a common trait for those with ED, along with perfectionism, and evangelizing is common.

Re obesity in the US – levels have actually flattened out in the past few years in most states, with a decline in others, and also childhood obesity. At the same time life expectancy has risen. I live in Australia currently, and life expectancy for men has just gone over 80 years for the first time in history, altho we are one of the ‘fattest’ nations; life expectancy for men in the early 1900s here was between 47 – 52, even though they were leaner, smaller and lighter. I worked for some years in the senior citizens sector, and we are being told to expect a ‘silver tsunami’ of seniors in the next few years,because people are living longer. this is one reason we see the term obesity paradox being used. There is a clear correlation between being overweight and actually living longer, altho it is still a matter for intense research at present. It is worth reading scholarly literature on the topic if you are interested.

A really good article if you can get hold of it is this “Integrating Fundamental Concepts of Obesity and Eating Disorders: Implications for the Obesity Epidemic

Ann E. Macpherson-Sánchez, EdD, MNS”, but you need access to the site to read it. It explains in well-referenced detail the connection between dieting and obesity, arguing that one of the most potent causes of obesity is calorie restriction – and explains how it is that ” lifetime weight maintainers depend on physiological processes to control weight and experience minimal weight change.” Those physiological processes are well known, and Gwyneth Olwyn is one of many who refer to them when encouraging people to recover in a manner that allows the body to regulate the weight, altho recent research shows that it make take as long as 6 years for the metabolism to correct itself, and for weight to return to set-point.

I hope you continue to enjoy youreatopia – it is a starting point at least for a different way of looking at recovery.

All the best to you as you continue on your own journey.

I understand this artucle was posted a long time ago, but fingers crossed I can still reply!

love and hugs to you.

love and hugs to you.

I turned to this article because I’ve been in recovery for just over one year. I’ve had good and bad times since but I’m no longer at a dangerously low bmi… quite the opposite actually, some therapists (who I no longer go to) suggested I get back into sports because I “seem fine”. Thank god I didn’t and I’m absolutely thriving with my bmi of 29.

I turned to this article today because I just started new jobs and on my day off I felt so overwhelmed and sluggish, I was tempted to go get a BK Burger for lunch rather than go to the grocery store for options and make a real lunch. I kept stalling however, and realized I felt scared. Was this a “bad” idea? Would this set me back on my goals? I took a break from my confusion to google “junk food in anorexia recovery” and found this.

Thank you so much for your thoughtful and thorough research. I identify stringly with that chart of how weightloss continues in AN. I remember how what used to be “bad” 5 years ago was joined by increasingly strict rules 2 years ago. I think my body could easily peg burgers and fries as unhealthy and unwanted but as my “success” with restricting continued, I grew more and more interested in choosing other fatty, caloric and dense foods to deprive myself of.

Thinking about it, I realized I’ve definitely worked backwards in my recovery. I began by eating “acceptable” foods in larger portions and added more and more restricted/scary foods to my diet. I think I’m just very far along as burgers still hold a bizarre point in my heart.

I am so glad to have a resource to pull from for some logical support. And I’m going to go get a burger now.