Another issue in defining and understanding recovery is that patients and clinicians may have different opinions about what recovery looks like and how to get there. Certainly, there is a body of literature from the critical feminist tradition in particular that explores how at times, patients can “follow the rules” of treatment systems to achieve a semblance of “recovery,” from a weight restoration and nutrition stabilization perspective, but feels nothing like a full and happy life (see, for example, Gremillion, 2003; Boughtwood & Halse, 2008).

This potential disconnect is one reason for favoring a holistic recovery as articulated by Bardone-Cone et al. and for attending to patients’ subjective experiences of recovery (see part 2 of this series here), as Malson and others have done (see part 3 of this series here). In 2006, Noordenbos & Seubring conducted a study that further unpacked this potential disconnect through a deeper examination of how individuals and therapists conceive of recovery. Carrie at ED Bites touched on this article in her recovery series here, but I’m hoping that this post helps to even further explore this study and how it relates to our ongoing search for a holistic and well-rounded understanding of recovery.

Recovery Criteria: The Patient and Clinician Perspective

To explore the similarities and differences between patient and provider orientations to recovery, the authors created a list of 52 possible recovery criteria based around the following domains:

- Eating behaviour

- Body experience

- Physical well-being

- Psychological well-being

- Emotional functioning

- Social functioning

In developing the list, Noordenbos & Seubring were guided by these domains and the following definition of recovery:

A patient has recovered from an eating disorder (ED) if she no longer displays the characteristics of eating disorders as defined in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), and no longer shows the somatic, psychological and social consequences of an ED

They broke their list down into the domains above. For example, items on the checklist get at:

- Eating behaviour: e.g., “eats three meals a day,” “amount of calories is normal,” etc.

- Body experience: e.g., “does not feel too fat”

- Somatic (physical): e.g. ,“weight is stable for 4 weeks,” “heartbeat is normal,” etc.

- Psychological: e.g., “has adequate self-esteem,” etc.

- Emotional: e.g., “is not depressed,” “is able to express emotions (verbally and nonverbally- 2 separate items),” etc.

- Social: e.g., “participates in social activities,” etc.

To clarify, though the authors put forth these 52 possible criteria as potentially representative of recovery, they were interested in finding out more about how well these resonated with both individuals who had experienced eating disorders and with clinicians. To this end, 41 former patients and 57 therapists selected criteria from the list according to how relevant they felt they were to the construct of “recovery” from eating disorders.

46% of the former patients had experienced bulimia, 34% anorexia, and 20% both AN and BN. Eating disorder duration ranged from 1-5 years (mean 4 years), with former patients having experienced 4 months to 5 years of treatment (mean 2.5 years), ending at least 6 months prior to the beginning of this study (and up to 3.5 years prior).

Therapists were recruited from the Dutch Foundation of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa: 39 were women and 18 were men. The authors do not comment on the type of therapy they provide (e.g., cognitive behavioural therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, narrative therapy, etc.) or the number of years they had been in practice. All, however, were specialist eating disorder therapists.

How Much Did Patients and Therapists Agree?

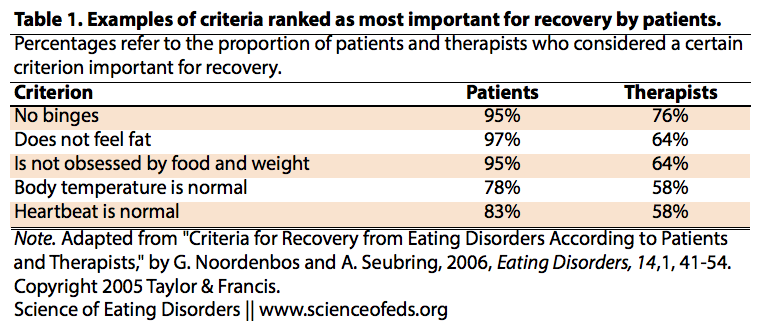

For the most part, clinicians and former patients held similar opinions about how relevant these criteria were to a well-rounded definition of recovery. Therapists and individuals with lived experience agreed (within 10% when rating on a scale from 0-100% importance) on 34 of the criteria. In general, patients thought that more of the criteria were highly relevant than did therapists, such as, surprisingly:

These were not the only criteria that patients found to be more important than did therapists, but I found these ones particularly surprising, especially those that are in the “somatic” category. I suppose it is possible that therapists consider things like heartbeat and body temperature to be outside of their domain of expertise and so might assume that general practitioners could attend to these more “physical” aspects of recovery. Still, a bit of an odd discrepancy.

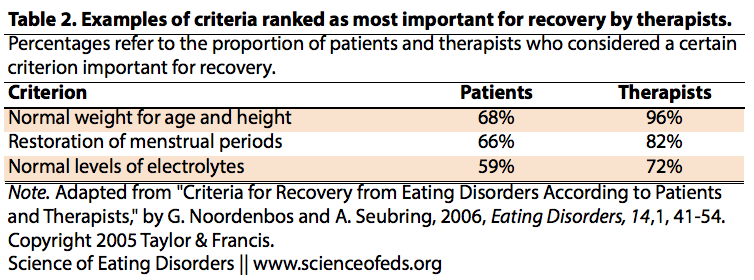

Interestingly, the criteria that therapists found to be more important than patients were also all in the “somatic” category, like:

Neither patients nor therapists thought that regular menstrual periods, healthy teeth and intimate relationships were pivotal elements of recovery. Sleep and bowel movement regularity were also areas that neither patients nor therapists found to be very relevant to recovery status.

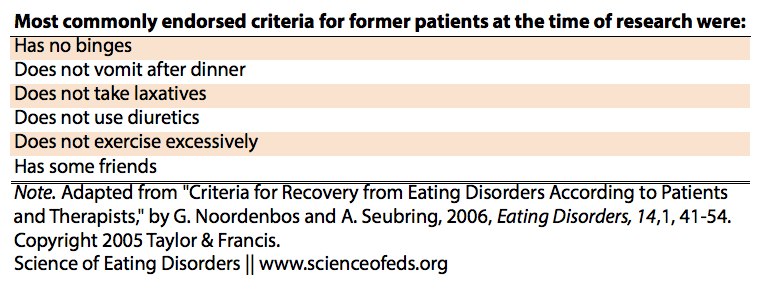

The authors took the responses rated as more than 80% important (by former patients) to be relevant to the definition of recovery. They then assessed (via self report) which criteria former patients felt they had met when they last finished treatment. Keeping in mind that recall approaches like this can be limited (i.e., it can be hard to remember what one felt like immediately after treatment, especially for those who had been out of treatment for longer):

- 80% reported that they no longer purged, took laxatives, used diuretics, and did not use diet pills

- Only half felt they met criteria for positive body attitude, appearance acceptance, regular menses, no constipation, sufficient assertiveness, perfectionism, and intimate relationships

Asking participants about which criteria they met at the time of the study, however, revealed that most felt much “improved” in terms of meeting recovery criteria, though some participants reported using laxatives and/or diet pills, having trouble participating in social activities, and reaching out to new contacts.

The most commonly endorsed criteria for former patients at the time of the research were:

Some of these seem a little vague to me; what does one mean when they say “some” friends or “excessive” exercise, for example? These statements could be interpreted in very different ways, making it difficult to get a real sense of what that aspect of recovery looks like for different people.

IMPLICATIONS

As Noordenbos & Seubring note, it can be hard to prioritize criteria for recovery, particularly in areas where consensus on best practices continues to elude researchers and clinicians (e.g., the arbitrary assignment of BMI values as marker of recovery, etc.).

I think the study is helpful in that it reveals that there are:

- Many different criteria that feed into the “recovery” equation

- Differences of opinions within and between groups of patients and clinicians about which of these criteria are important

However, as always I wonder about the stories behind the numbers here: what might lead former patients and therapists to evaluate certain criteria as important over others?

The authors also note that the major differences in the criteria former patients felt they met and the fact that no former patient met 100% of the criteria might indicate that full recovery is illusive. However, I would complicate this slightly: I think that this finding reflects the idea that recovery looks extremely different, depending on a number of factors including but not limited to:

- How long they struggled with the disorder

- Age at onset and age at treatment

- Treatment experiences

- Social support network, including friends and family

- Systemic factors, such as access to (affordable) healthcare

- Personal life goals

- Comorbid conditions

- Cultural norms in broader society and in individual social networks

Obviously, there is no one definition of recovery that is going to capture all of these factors. Still, I think it is worth noting that not meeting criteria on a checklist, no matter how well researched in its generation, does not mean that one is not “recovered” or that recovery is not possible. It might just mean that recovery is inherently a concept with many shades of grey.

References

Noordenbos, G., & Seubring, A. (2006). Criteria for Recovery from Eating Disorders According to Patients and Therapists Eating Disorders, 14 (1), 41-54 DOI: 10.1080/10640260500296756

“Still, I think it is worth noting that not meeting criteria on a checklist, no matter how well researched in its generation, does not mean that one is not “recovered” or that recovery is not possible. It might just mean that recovery is inherently a concept with many shades of grey.”

Yes! I really think meeting every single criterion of recovery is difficult for the list of reasons you mentioned in your post. Does that mean total recovery is illusive? I don’t think so. As a person who identifies as recovered, I still deal with perfectionism and don’t always feel great about my body. I don’t think this makes me partially recovered, though others may disagree.

Yeah, this was my biggest issue with the authors’ interpretation of the results- it seems pretty unrealistic to me to expect people to experience recovery in the same way given all of the variables- also for recovery experiences to remain static over time. For example, one day might be a great “body image” day while the next, not so much. I feel like that’s a pretty “normal” (whatever that means) part of life, let alone recovery!

I have been recovered for the best part of twenty years and yet, just occasionally (maybe once or twice a year?), I somehow slip into an unplanned binge–which for me is over-eating to the point of physical pain.

Thanks for your comment Natasha. I’m wondering, how does the fact that you engage in binge eating still (albeit very rarely) affect your definition of your own recovery?

I consider myself to be recovered because I do not engage in the day-to-day behaviour of bingeing and fasting. I’m not trying to lose weight, I don’t own a pair of scales, I eat when I’m hungry, etc.

I feel immensely relieved and grateful that I managed to escape that prison after seven years.

So if, say at Christmas, when there is a huge amount of food around and I’m drunk, and other people are stuffed but still eating too, and I keep on eating, even though it’s pretty uncomfortable, I don’t consider that to be bulimic behaviour. I don’t think I have relapsed.

I find these findings rather surprising, too. I’ll read the paper and respond in full later (hopefully). Some of the criteria seem like obvious/setting a low bar while others seem bizarrely specific/largely irrelevant for a lot of people in recovery.