In the 1980s, a few studies came out suggesting that patients with bulimia nervosa (BN) require fewer calories for weight maintenance than anorexia nervosa patients (e.g., Newman, Halmi, & Marchi, 1987) and healthy female controls (e.g., Gwirtsman et al., 1989).

Gwirtsman et al. (1989), after finding that patients with bulimia nervosa required few calories for weight maintenance than healthy volunteers, had these suggestions for clinicians:

When bulimic patients are induced to cease their binging and vomiting behavior, we suggest that physicians and dietitians prescribe a diet in which the caloric level is lower than might be expected. Our experience suggests that some patients will tend to gain weight if this is not done, especially when hospitalized. Because patients are often averse to any gain in body weight, this may lead to grave mistrust between patient and physician or dietitian.

Among many things, this ignores the fact that patients with bulimia nervosa, despite being in the so-called “normal” weight range may not be at their healthy weight.

It is not possible to determine at this point whether the abnormality in energy utilization is a trait-related phenomenon or is caused by the binging and vomiting or by cycles of weight loss. However, it is well known that vomiting is an effective means of weight control. Unless bulimic patients are counselled about dietary intake with the above considerations in mind, they will return t0 vomiting as a means of weight control.

First, there’s the assumption that individual vomit mostly or solely as a means of weight control. Second, this ignores that patients might be binge eating and vomiting precisely because they are restricting their caloric intake and/or foods in the first place.

Although there are no known chemical means of altering energy efficiency, we suggest that physicians and dietitians prescribe regular aerobic exercise as an integral part of the treatment program for a proportion of their normal weight bulimic patients provided there are no contraindications to such exercise. Perhaps this will allow bulimic patients in the abstinent phase to attain a relatively normal intake for weight and height.

I hope you can tell that was written over 20 years ago, and I hope the problems in these suggestions are equally apparent.

Perhaps an aside, but as I was reading some of these older studies, I was almost immediately struck by the caloric intake of the healthy controls. In Gwirtsman et al. (1989), the average intake in the healthy control group was just a bit under 1,700 calories/day. This is for a group with an average age of 23 and an average BMI of 21. In Kaye et al. (1986), the average intake for healthy controls was 1,725 calories/day. Seems kind of low to say the least! For BN patients (average age: 24, average BMI: 19.7), Gwirtsman et al. (1989) determined that patients needed an average of 1172 calories/day to maintain their weight, and in Newman et al. (1987), the number was 1506 calories/day.

These older studies employed fairly similar methodologies. Essentially, BN patients had to maintain a stable body weight (within 1kg), and their caloric intake was calculated based on how much food was left uneaten from the hospital kitchen plates. In some cases, patients were monitored 24/7 to make sure they couldn’t binge and/or purge. In some, but not all cases, the patients were symptom-free for weeks before the study took place. Healthy controls and other patient groups followed similar procedures.

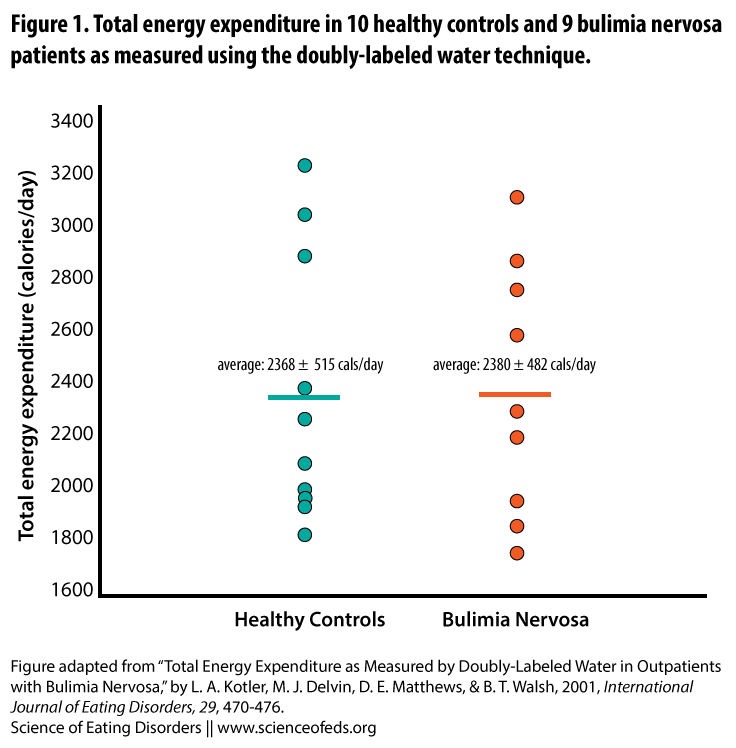

However, studies utilizing better methods to evaluate caloric intake in BN patients, in particular, the doubly-labeled water method, found different results. This method allows researchers to see how many calories individuals expend without having to weigh leftover food to estimate calories consumed. In one such study, Kotler et al. (2001) looked at caloric needs in symptomatic, outpatient BN subjects, found no differences in the total energy expenditure between healthy control and BN groups. What’s more, the average energy expenditure in these groups seemed a lot more reasonable (~2350-2400/calories per day):

BN patients in Kotler’s (2001) study had been ill for an average of 12 years and had an average of 15 bingeing and 17 purging episodes a week. So, you know, fairly symptomatic. This led the authors to conclude that, contrary to previous hypotheses and findings (like those mentioned in the studies above),

These data suggest that the energy conserving metabolic adaptations characteristic of semi-starvation do not occur in patients with bulimia nervosa.

Researchers initially thought that bingeing and purging might put patients with BN in a state of semi-starvation, but this data suggests that this might not be the case.

Ten years prior, Pirke et al. (1991), also using the doubly-labeled water technique, found similar results: The BN group expended an average of 2,510 calories/day (average BMI 19.7) and the healthy controls expended 2,357 calories/day (average BMI 20.0) (these differences were not statistically significant, although the BN group did exercise for about 20 minutes more a day, on average).

There are, however, important differences between all these studies. For one, patients in the Gwirtsman et al. (1989) study were in a hospital setting and were not symptomatic during the study period (although a subgroup was hospitalized for only 5-8 days and were symptomatic prior to this hospitalization). This is not true for subjects in Kotler et al.’s study who continued their usual eating patterns (including binge eating/purging). In Pirke et al.’s study, although patients were hospitalized for 3-6 weeks, the authors wrote that binge eating and purging persisted in about half of their BN group. These types of differences between the studies make comparing the derived caloric intake and total energy expenditure values difficult.

Taken together, the total energy expenditure findings using the doubly-labeled water method (i.e., Pirke et al.’s and Kotler et al.’s studies), it seems that BN patients do not differ from controls in the amount of calories they expend per day. It seems there is a consensus here. The same cannot be said of the findings regarding resting energy expenditure (a subset of total energy expenditure). These studies have revealed contradictory results. In a review paper, de Zwaan et al. (2001) wrote:

In summary, the results regarding BN are inconsistent, with some investigators finding reduced levels and others finding elevated levels of [resting energy expenditure] at baseline. Longitudinally, some studies reported a decrease, others no change or even an increase in [resting energy expenditure] during abstinence compared with the acute phase of the illness. The reason for these inconsistencies is unclear.

In their study, Kotler et al. concluded,

Although this study provides no evidence for the idea that individuals with BN are in a physiological state of semistarvation, the limitations of the study design do not allow us to dismiss this idea entirely. In addition to measuring TEE and its individual energy components, it would be useful to measure TEE in the same patients both while symptomatic and after recovery. The occurrence of significant alterations in energy regulation during recovery might have important implications for the nutritional rehabilitation of patients with this illness.

Although that study was published more than 10 years ago, I have not come across a study evaluating energy expenditure (and its individual components) in the same patients during the ill and recovered state, so the jury is still out on what happens to BN patients’ metabolisms during and after recovery. Perhaps the higher total energy expenditure during the acute phase is higher than what it would be if patients were not symptomatic. The answer is not clear.

It is important to emphasize, however, that when it comes to studies evaluating total energy expenditure or its various components in ED patients, particularly those who engage in bingeing and purging behaviours (because that can complicate the calculation for things like total energy intake) is just how many factors affect the results. As pointed out by Kotler et al. (2001), discrepancies in studies could be due to, among many other factors:

differences in methodology and in clinical status of the subjects, severity of binge eating and purging, impact of diet, smoking and physical activity, as well as differences in measurement techniques.

In sum, the main findings from the studies using the doubly-labeled water technique is that there are no differences in the total energy expenditure in BN patients and healthy controls. But we don’t know for sure, yet, the effects of bingeing and purging on total energy expenditure and resting energy expenditure (and thus, what happens to these during the course of recovery).

And while, as de Zwaan et al. (2001) note, energy measurements are not routine in the care of ED patients, and we don’t know if and to what extent binge eating and purging behaviours affect resting metabolic rate and/or total energy expenditure, I sincerely hope that we can put the suggestions to clinicians in Gwirtsman et al.’s (1989) paper behind us, because well, for one, we don’t actually know if patients require fewer calories to maintain their weight, and two, we probably should not be promoting dieting behaviours and weight suppression in treatment, to say the least.

References

de Zwaan, M., Aslam, Z., & Mitchell, J.E. (2002). Research on energy expenditure in individuals with eating disorders: a review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31 (4), 361-9 PMID: 11948641

Gwirtsman, H.E., Kaye, W.H., Obarzanek, E., George, D.T., Jimerson, D.C., & Ebert, M.H. (1989). Decreased caloric intake in normal-weight patients with bulimia: comparison with female volunteers. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49 (1), 86-92 PMID: 2912015

Kotler, L.A., Devlin, M.J., Matthews, D.E., & Walsh, B.T. (2001). Total energy expenditure as measured by doubly-labeled water in outpatients with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29 (4), 470-6 PMID: 11285585

This is really really interesting. What do you think of studies that divide the BN groups into those with a prior history of AN and those without? (This study is the only one I could find offhand, as an example: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1957930 I wonder if that’s some of where the BMR discrepancies come from?

I have a lot of opinions in general about the nuances of BN. I think BN as a result or prior restricting (or full-AN) is a much different disorder from BN as a standalone with no restriction or prior restriction. But I have no real research to back that up!

Sorry for the delay in responding!

So, I don’t think much of those studies tbh (with the big caveat that there are a few and they are all different and I can’t keep them straight in my head). I think the studies following those (e.g., the ones using DLW technique) suggest otherwise, and DLW is a much, much better method of testing these types of things. Granted, the studies using DLW and the one you linked to (Weltzin et al., 1991) are different in many ways, one being that the DLW studies didn’t look at long-term vs. short-term weight stable.

In the study you linked to, for the long-term weight restored BN patients with and without AN history, there were no differences in caloric requirements. They only found a difference between short-term weight restored AN-R patients and short-term weight restored AN-BP (with the latter requiring more calories). But I think this could easily be explained with the fact that those in the AN-BP group were 81.4% of their highest weight whereas those in the AN group were at 98.6%. To me, this suggests the AN-BP group is still quite weight suppressed! The BMI differences were not statistically different, BUT the AN-BP group might have a naturally higher BMI.

To me, this suggests the AN-BP group was probably weight stable at a weight that’s too low for them, as a group. Indeed, all of the BN groups in the study were between 80-87% of their highest weight (compared to 98.6% for the AN group).

Again, to me, suggests the weight they are maintaining in the study is actually too low. It is possible their highest weight wasn’t their “healthy” weight, for sure, but I am suspicious that 80% of height weight, despite that being a BMI of 19.4 for that group, is *actually* a healthy weight. So, I suspect they are metabolically suppressed.

The study you linked to didn’t calculate BMR.

This would make sense given that studies have shown that BN patients tend to have higher previous weights than AN patients. (This also makes sense since they are less likely to get to the weight/BMI required for AN diagnosis compared to patients who start out at a lower weight.)

The calories required/day in these older studies using the whole method of feeding people a known amount of calories and then seeing what they ate off a plate tend to lead to pretty big underestimations of required calories when you compare them to the DWL studies. (I mean, 800-1000 cals/day difference — BIG differences).

With regard to differences between BN who have and have no had AN history, I think it depends on what you mean by “difference” and what you mean by “restriction”. A lot (most, probably) of people with BN who do not/never had AN do restrict — they just don’t lose weight. They don’t have long periods of restriction — they might only eat at night, for example. Skip meals. Or avoid certain foods. So that restricting binge/purging pattern may be present just to the same extent. The diagnosis of AN depends on getting to quite a low weight that for most people whose natural weight is high/higher is just impossible anyway.

What do you mean by “differences”? Physically? Psychologically? Both? Something else?