Much research has been done on personality traits associated with eating disorders, and, as I’ve blogged about here and here, on personality subtypes among patients with EDs. For example, researchers have found that individuals with AN tend to have higher levels of neuroticism and perfectionism than healthy controls (Bulik et al., 2006; Strober, 1981). Moreover, some traits, such as anxiety, have been associated with a lower likelihood of recovery, whereas others, such as impulsivity, with a higher likelihood of recovery from AN (see my post here).

Personality refers to “a set of psychological qualities that contribute to an individual’s enduring and distinctive patterns of feeling, thinking and behaviour” (Pervin & Cervone, 2010, as cited in Atiye et al., 2014). Temperament is considered to be a component of personality and refers to, according to one definition,”the automatic emotional responses to experience and is moderately heritable (i.e. genetic, biological) and stable throughout life.”

One popular model for classifying temperamental traits was developed by Cloninger (1987) and consisted of three dimensions (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and reward dependence). The model has been updated with the addition of persistence as another dimension of temperament (Cloninger, Przybeck, & Svrakic, 1991). These four traits (described below, with the exception of persistence) are measured by the Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI):

Novelty seeking is a tendency for intense excitement or exhilaration in response to novel stimuli or cues for potential rewards or potential relief of punishment, harm avoidance is a tendency to respond intensely to signals of unpleasant stimuli, which leads to inhibition behaviour in order to avoid punishment, novelty or frustrating non-reward and reward dependence is a tendency to respond intensely to signals of reward, which leads the subject to maintain or resist the extinction of behaviour that has previously been related to rewards or relief from punishment.

While a lot of research has been done on temperament in eating disorder patients, there has not been a comprehensive summary of the findings. Consequently, the authors of this paper, Minna Atiye and colleagues, sought to utilize a meta-analytical approach to summarize the studies published to date studying temperamental traits (using Cloninger’s model) in ED patients.

THE STUDY

The authors searched for studies on EDs using Cloninger’s temperament dimensions. There were 14 case-control studies that fulfilled the criteria, with 8 studies including more than one patient group. There was a total of 3315 cases (i.e., individuals with an ED) and 3395 controls:

- 11 studies had AN patients (446 cases)

- 7 studies had AN-R patients (345 cases)

- 7 studies had AN-BP patients (471 cases)

- 12 studies had BN patients (1485 cases)

- 2 studies each had EDNOS (185 cases) and BED patients (383 cases)

Men were included in 4/10 studies, comprising 2.2% of the cases and 5.3% of the controls (72 and 179 individuals, respectively). Two studies included individuals who had recovered from an ED (295 individuals).

MAIN FINDINGS

Comparisons between individuals with and without EDs

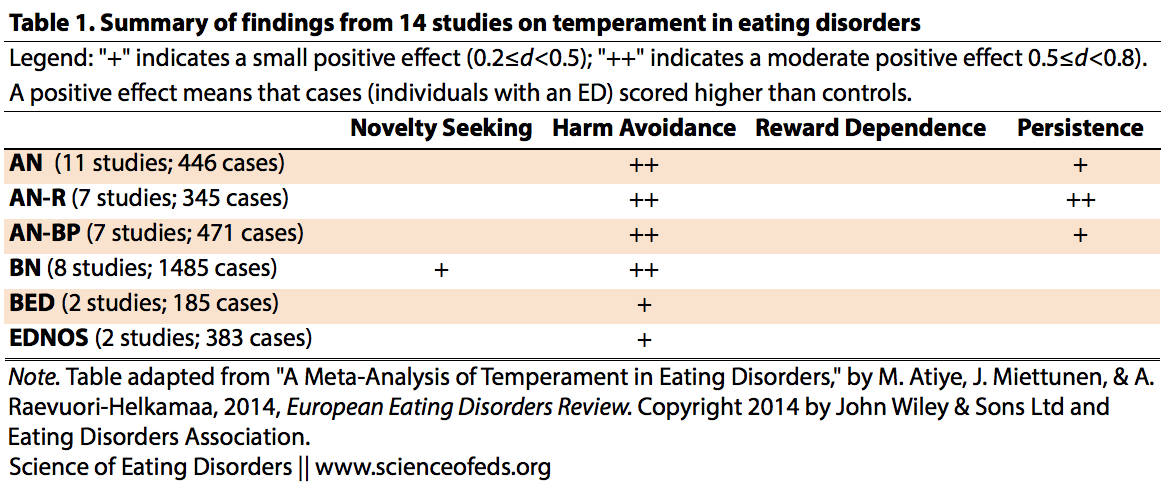

The table below summarizes the pooled effect sizes for differences in the four temperament dimensions between individuals with and without EDs. For simplicity, I excluded statistically non-significant effect sizes greater than 0.2, which were included in the original table. (More on interpreting effect sizes here).

As you can see, novelty seeking is significantly higher than in controls on in individuals with BN (d=0.41). On the other hand, compared to controls, harm avoidance was elevated among all diagnostic groups. Harm avoidance was highest in the AN-R and AN-BP groups (d=0.76 for both).

Reward dependence did not differ between individuals with EDs and controls for any diagnostic groups. Finally, persistence was elevated in individuals with AN, with the highest effect sizes in those with AN-R (d=0.52).

Comparisons between ill and recovered individuals

Only two studies compared ill and recovered individuals (total number of cases: 159). Differences were observed only in the AN group, with harm avoidance being significantly lower and reward dependence significantly higher in those who had recovered compared to those who were ill.

WHAT DO THESE FINDINGS MEAN?

Before I get into what the findings mean, I think it is important to point out that the majority of the studies included individuals with “current or lifetime” eating disorders. I suspect the vast majority of the studies were done when patients were ill. This, of course, raises the question: Are these traits premorbid, and do they predict ED onset, or are they somehow altered because of the ED itself?

As mentioned above, individuals with AN had the highest scores among the diagnostic groups on harm avoidance and (specifically for AN-R) on persistence. The authors suggest that this may mean individuals with AN have “an even stronger tendency towards fearfulness and worry” (harm avoidance) as compared to the other diagnostic groups and may explain why individuals with AN have “a strong tendency to maintain behaviour despite frustration and intermittent reinforcement” (persistence).

With regard to the high novelty seeking scores among the BN group, the authors suggest that this is “in line with established observations of impulsive and borderline traits” among individuals with BN. Although I did not include it in the graphic, the authors found a nonsignificant reduction of novelty seeking (relative to controls) among those with AN.

Regarding differences between ill and recovered individuals, Atiye et al. write that these findings “suggest an improvement in social interactions and an alleviation of anxiety along with recovery from AN.” Maybe, maybe not (see limitations below).

IMPORTANT LIMITATIONS

There are important limitations to consider when interpreting these findings. First, the results for BED and EDNOS come from only two studie. The results for EDNOS are especially tricky to interpret because the diagnostic group is very heterogenous, and the results for BED come from only 185 cases, compared to, for example, 1485 for BN.

Second, there were only two studies that compared temperamental traits between ill and recovered individuals. Importantly, these comparisons did not look at the same group of individuals over time, assessing them when they were ill and then again when they were deemed to be recovered. Instead, they took individuals who were ill and compared them to a different group of individuals who were recovered. Thus, we don’t know whether the process of recovery leads to lower harm avoidance and higher reward dependence OR that individuals who have lower harm avoidance and higher reward dependence are more likely to recover. This is an important question, and one that requires longitudinal research.

Third, there’s evidence of a publication bias (also called the file-drawer effect) in three comparisons: harm avoidance in AN and BN, and persistence in AN. Publication bias refers to the fact that studies that do not find a positive effect are less likely to be published. So when researchers decide to do a meta-analysis and combine all of the published research on a topic to see where the consensus lies, they may be misled and conclude that the effect they are seeing is greater than it really is in reality. What does this mean here? It means that the differences between individuals with EDs and healthy controls on harm reduction in AN and BN and persistence in AN might not be as big as we think. It is hard to say.

FUTURE RESEARCH

We need longitudinal studies. Longitudinal studies will not only help us understand what, if anything, happens to temperamental traits during and after recovery, but also what, if any, traits can predict recovery. In the future, we might be able to use this information to also predict what treatment approaches might work best for individuals depending on their temperament.

More interesting to me, however, is that longitudinal studies might be able to tell us what happens regarding temperament when individuals cross over from one diagnosis to another. This happens fairly frequently (more for some diagnostic crossovers than others, though), as I’ve blogged about before. And I have often wondered what this high rate of diagnostic crossover means for studies that evaluate individuals with EDs at a single time point and then compare different diagnostic groups, whether they compare prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, temperamental or personality traits, or anything else.

So, how different are individuals with AN compared to those with BN really? And, how much of the differences that we see are due to premorbid differences and how much are they byproducts of the current (ill) state? I am not claiming there are not differences — there are, of course there are. Certainly, many people do not crossover, and crossover rates differ depending on initial diagnosis. Still, is it possible that we are overestimating the differences between these diagnostic groups? And how elastic, or state-dependent, are temperamental and personality traits (or are the differences/changes we see due to imperfect measuring instruments)?

On this, the authors write,

The general assumption posits that temperament is relatively stable over time (Goldsmith et al., 2000), but significant changes in psychiatric disorders in response to state effects have also been reported in longitudinal designs (Abrams et al., 2004; Kampman et al., 2012).

I’m looking forward to potentially seeing some longitudinal studies addressing these questions soon. Readers, what are you thoughts? In particular, do you feel your temperamental traits changed throughout the eating disorder? If so, do you feel the temperamental changes led to changes in the ED “status” (i.e., from illness to recovery, or a diagnostic crossover) or vice versa?

References

Atiye, M., Miettunen, J,, & Raevuori-Helkamaa, A. (2014). A Meta-Analysis of Temperament in Eating Disorders. European Eating Disorders Review PMID: 25546554

I’m also really curious about correlations with the INFJ etc. test.

I was recently on a pro-ana forum, and they posted a link to this test and polled people. n ~ 1,200. And nearly everyone was INFJ. Most others were some variant of INxx.

Super interesting.

Dear A,

Boy, you would not be the first to comment on the apparent number of INFJ’s among those with EDs. I’ve been on a number of different sites over the years where M-B results were taken, and just as you pointed out, it’s been really difficult to ignore just how many INFJs there are in comparison to other types. Since INFJ is supposed to be one of the very least common of all the types, a person is certainly tempted to draw some conclusions from that.

On the other hand, “professionals” all seem to have a big problem with the M-B, as ( to be frank) it wasn’t developed by members of their club, so despite the glaring proportion of people with EDs who appear to score as this type, I doubt we’ll ever see any research regarding this fact.

Still, the fact that people with EDs seem to consistently produce disproportionate results on *any* sort of test would seem notable, and worthy of further investigation. Particularly if such results appear to vary in rather dramatic ways from those of the general public.

As an aside, what exactly “harm avoidance” is supposed to mean, within the framework of EDs, seems rather hazy and open to interpretation . It’s an interesting outcome, but without the ability to pin down it’s meaning in ways that all might agree on, I’m not really sure what it’s usefulness is.

Hi Bob,

I don’t think it has anything to do with it not being developed by their members of the club. Instead, it is because it is questionable whether the test meets certain criteria for being seen as a useful tool to assess personality traits. It doesn’t mean it is 100% bunk or something, but probably that it is not good *enough*. And don’t get me wrong, I loved thinking it was awesome and identifying as an INTJ, which is what I usually got when I did various online incarnations of it. It seems to be really popular because it is been commercialized and made profitable. The company offers training guides, workshops, and has trademarked nearly everything it seems. I find it odd that people so readily jump at criticizing “Big Pharma”, but are not so quick to question these types of tests when it is clear to me that large part of their popularity is to do with the fact that someone is making a big buck marketing it as scientific. Researchers are generally not interested in commercializing their psychometric tests. Here are some articles on the issues with MBTI:

Nothing personal: The questionable Myers-Briggs test — The Myers-Briggs personality test is used by companies the world over but the evidence is that it’s nowhere near as useful as its popularity suggests.

Goodbye to MBTI, the Fad That Won’t Die

The Wikipedia page on harm avoidance is actually pretty good at distilling what the main components of that temperamental dimension are (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harm_avoidance). I think the four subcomponents make it fairly straight forward, although I do find it interesting that “shyness” is in there. I agree the name of the term is rather odd; I think it could’ve been better labelled.

Cheers,

Tetyana

Hey Tetyana, thanks for the kind reply.

I’m just a MB fan I’ll admit, and to be honest I only know of one person who’s paid to take the MB, while I know I’ve ended up paying quite a bit to take other more formal tests, whether those who developed them wished them to be monitized or not.

As far as the MB goes, I can see where there could be some argument as to whether the traits it measures truly are the most significant components of personality. As I understand there’s been plenty of discussion over the years as to just which aspects of a person’s temperament should be considered, when it comes to producing a global assessment of personality. Despite Cloninger’s model, and now the Big Five, I suspect it’s a discussion that will continue, far into the future.

That discussion aside, it does seem that the MB fairly assesses *some* aspects of a person’s personality. And if some of those aspects appear to be particularly prominent among people with EDs, there would seem to be value in taking a look at those aspects, particularly if the results appear robust.

That being said, whenever this topic comes up on one of the forums, and the results begin stacking up, sooner or later someone will point out that perhaps what’s actually being measured is the personality of people who choose to come to support sites. Introverts, and the “NF” type of personality may be attracted to places where the nature of the human condition is revealed and explored, and where emotional support is exchanged. So the population being sampled is likely not a random one.

Given all that, it’s still as A said in her original post : No doubt about the fact that there seems to be a hugely disproportionate number of INFJ’s on ED support forums, when compared to the number of INFJs in the general population.

Hi Bob,

Thanks for the reply! A few comments:

I don’t have much issue with MBTI as a fun thing to do online. My issue is more with the assertions that what someone gets on this (or any other test) shows something significant about what kind of a career they’ll excel at, or something of that nature. It is scary to me that HR departments administer these tests. (Just check out: http://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/. I think MBTI really overreaches with regard to what the test results say about the person.

I agree. I think the debate will continue. Ideally, we want to capture as much variance as possible with fewest number of variables.

Well, MB is not completely BS, of course, but I think for the simple fact that we all feed information into these tests (MB, Big Five, TCI, etc.) about ourselves. I used to be able to guess what MB type someone would get after knowing them for a little while. The results we get are directly based on what we write/answer about ourselves. My question is: Does it capture those aspects better than the Big Five or say, the TCI? I have no idea (honestly, I really don’t; I don’t think anyone compared this).

This is a very, very good point! I also wonder how they got the original prevalence percentages. Do you know?

Great post, Tetyana. I definitely think ED recovery contributed to changes in the expression and intensity of my temperamental traits, though I can’t say it alleviated them all together. I have trended towards anxiety for most of my life, but the anxiety was particularly heightened during the 4 years of my ED. During that time, social interactions were often excruciating because of the food involved, and the obsessive ED thoughts that contributed to social anxiety (people are judging what I’m eating/not eating, I look disgusting eating this, how can I politely say no to this food or ask for a substitution without raising alarm or offending people, etc). I’ve been in recovery for 2.5 years, and in keeping with Atiye et al.’s summary, I certainly experienced “an improvement in social interactions and an alleviation of anxiety along with recovery from AN.” Social situations became much easier when I wasn’t worried about food or constantly thinking those obsessive, negative thoughts.

However, I would hypothesize that the relationship between pre-existing anxiety (or other temperamental traits) and social interaction in recovery is mediated by treatment approach or adherence. I have been in weekly psychotherapy with an ED specialist for the majority of my recovery, and throughout the first year, completed CBT exercises (food logging in combination with, thought records & emotion ratings, etc) 6x a day using a cell-phone app. These treatment strategies worked not only to reduce my ED-related anxiety issues, but I think they were instrumental in teaching skills for reducing anxiety after the initial period of recovery, when my ED symptoms had subsided but I still needed to find better ways to cope with the anxiety that was still there, after I couldn’t quiet it with ED behaviors anymore. Learning how to cope with my trait anxiety through treatment increased my later ability to be social. I agree with you that cross-sectional studies (or anedocatal data, in my case) are not enough- we need longitudinal research! Though I would have to imagine this is a difficult population to engage in longitudinal research appointments, as the isolating symptoms seen in those with the disorders tend to persist or increase in adults with AN who have remained ill for 10+ years (if I remember the research correctly), but that’s just a guess. Anyways, thanks for presenting this interesting research- love your site and the commitment to empirical research!

Hi J,

Thanks for your comment! I think you are right about the difficulty of doing longitudinal research. I think the other is simply monetary: longitudinal research takes a lot of money. And, of course, it is hard to do because people move around a lot, it is often hard to track them down, etc. So, basically, it is the usual things that make that research difficult + ED population + limited funding for ED research.

“However, I would hypothesize that the relationship between pre-existing anxiety (or other temperamental traits) and social interaction in recovery is mediated by treatment approach or adherence.”

Do you think it is treatment approach or just a byproduct of recovery and learning to manage anxiety/depression (/whatever ED symptoms ameliorate)?

Thanks for the reply, Tetyana!

I’m a few years out of grad school now (and this has never been my research area) so I’m not as familiar with the current literature on EBTs for EDs as I could be (and I know good research on EBTs in this population is limited, particularly longitudinal, for the reasons you pointed out), but from what I remember, I think CBT (or Maudsley/FBT for younger patients in families where this is appropriate) is still considered by most professionals in the field to be the first-line approach for psychotherapy (in combination with medication tx when indicated)- but please correct me if I’ve missed the latest research on this topic. I know that we also don’t have enough information to generalize research findings to everyone with an ED (particularly the understudied EDNOS/BED/Purging Disorder/”Atypicals”/ other “minority” groups- maybe males, LGBTQ folks?), but in my own personal experience (n=1 for the win, haha!), CBT tools were particularly critical in my recovery.

CBT techniques helped me learn the tools to manage anxiety successfully enough to recover, when other psychotherapy had not had that effect. Now, I also believe there were other contextual factors that made me more ready/able to work towards recovery at that time, but I have to say that returning to those tools absolutely kept me from relapsing several times during periods of stress. Using the CBT techniques helped me work through the anxiety and allowed me to engage more in social situations.

You raise a good point, it’s hard to say whether that might have happened on its own to some extent as a byproduct of some other aspects of recovery (weight restoration or adequate nutrition positively influencing executive functioning/emotion regulation, maybe?), or if that same result could be achieved through different approaches, that would work better for those for whom CBT has not been effective, or if it’s not accessible.

I am always interested in learning more! Since this is your speciality I look forward to hearing what you think, and it’s very possible I missed a post of yours that outlined research describing different treatments and outcomes, if you want to point me in the right direction Thanks again!

Thanks again!

People typically claim CBT as being an EBT for BN (and BED, I believe), but not really for AN. FBT/Maudsley for young AN patients. But, the studies are so limited, and you know, manualized therapies are rarely applied in practice the way they are in a study. It is just hard to say. It is not like we are treating one form of cancer with a very specific etiology and pathology, obviously. There’ve been studies showing that the particular form of therapy doesn’t seem to even matter that much. I think many people find CBT skills useful, however. I just wonder how much of the changes you’ve experienced are typical of people as they recover, regardless of whether they are utilizing CBT or DBT, or a mix of them, or something else entirely. I think it may be a mix of just pure nutritional improvement (but that might be felt more acutely by those who are malnourished), decreasing anxiety over food/weight, and general improvement in emo-reg.

It is definitely not my speciality! I worked on synaptic development in C. elegans in graduate school, haha.