A single in-lab assessment of caloric consumption, loss, and retention during binge-purge episodes in individuals with bulimia nervosa (BN) is frequently cited as evidence that purging via self-induced vomiting is an ineffective strategy for calorie disposal and weight control (Kaye, Weltzin, Hsu, McConaha, & Bolton, 1993). These findings have been widely interpreted to mean that, on average, purging rids the body of only about half of the calories consumed, regardless of total quantity.

However, a closer examination of the study does NOT support the notion that purging is an ineffective compensatory behavior. Indeed, the findings of Kaye et al. (1993) would appear to have been both misunderstood and overgeneralized in the subsequent decades. This has important implications for therapeutic alliance in clinical practice as well as for understanding the nature of symptoms, metabolic processes, and physiological alterations in EDs.

THE STUDY

The study included 17 individuals, all of whom had the diagnosis of BN and were of “normal weight” (i.e., >85% of average body weight for their age and height). Three patients were inpatients, two were outpatients (OP), and twelve were going to be starting OP.

After an overnight fast, the participants were instructed to pick items out of a vending machine and “binge in the laboratory as they would binge at home.” There were no restrictions on time or amount of calories they could eat. They were given a plastic bucket into which they could vomit. The authors used “proximate analysis” to measure the amount of calories in the vomit.

THE RESULTS

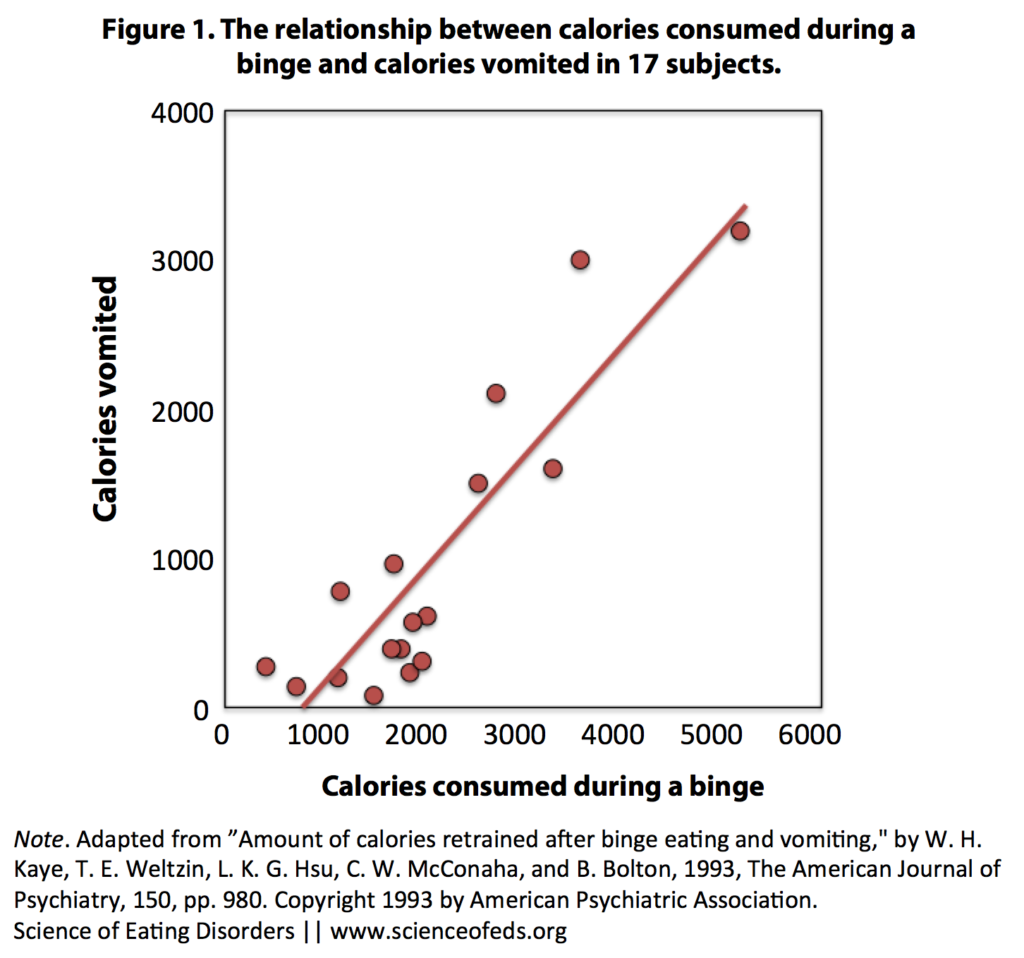

The figure below shows the relationship between calories consumed during a binge and calories vomited in 17 subjects. As you can see, 12 of the 17 subjects consumed 2,110 or fewer calories during their binge (this is the number Kaye et al. cite). Only 5 of the 17 subjects had binges of over 2,600 calories.

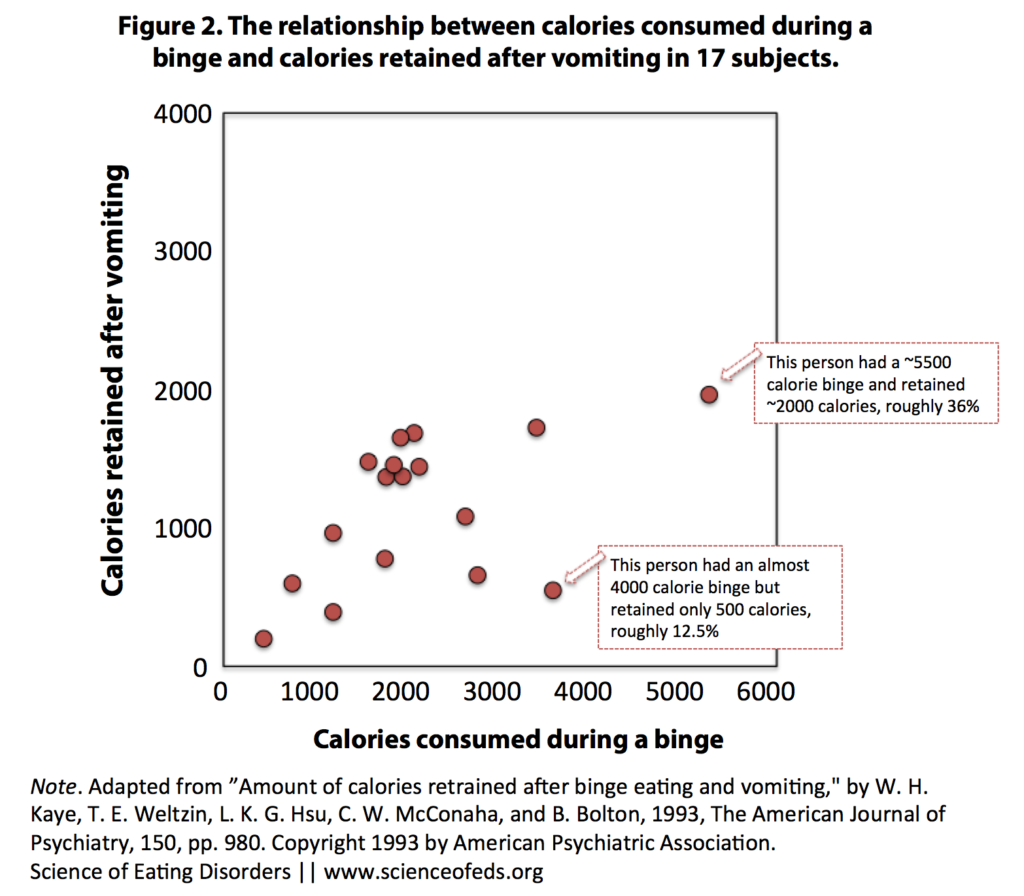

This figure shows the relationship between calories consumed during a binge and calories retained after self-induced vomiting.

MISINTERPRETATION

While whether a 50% loss of calories is deemed effective or non-effective comes down to individual goals and the definition of “effective,” Kaye et al. (1993) do not conclude that their results demonstrate that purging gets rid of half of the calories in a given binge. Rather, the “50%” likely results from the fact that the average number calories retained after purging (approx. 1,200) were about half of the calories of the average binge (around 2, 200 calories) among the study participants.

The authors refer to the number retained as a “ceiling” and not as representing a proportion of the total binge as the “1,200 calories” appears to have been misunderstood.

Even without taking into account considerable individual differences in physiology (e.g., the rate at which one’s stomach empties [gastric emptying time]), and purging motivation, ability and techniques), the 50% retention rate may only hold true for those whose binges are comparable to the mean binge amount for the group in the study. Indeed, the authors mention that a linear relationship between calories consumed and purged only held true for those whose binges contained fewer than 2,110 calories (mean (M) = 1,549, standard deviation (SD) = 505). They did not find a linear relationship between intake and calories retained for binges that contained more than 2,626 calories (M = 3,530, SD = 438). Importantly, only five participants had binges that were more than 2,626 calories.

From their abstract:

In 17 normal weight bulimic patients, there appeared to be a ceiling on the number of calories retained after vomiting. That is, whether or not bulimic patients had small (mean = 1,549 kcal, SD = 505) or large (mean = 3,530 kcal, SD = 438) binges, they retained similar amounts of kilocalories (mean = 1,128, SD = 497, versus mean = 1,209, SD = 574, respectively) after vomiting.

Contrary to the assertion that purging is ineffective, Kaye et al. in fact draw the exact opposite conclusion from their findings, reporting in their discussion that:

Bulimic patients retain similar amounts of calories when they consume more than 2,600 kcal and when they consume fewer than 2,100 kcal. Thus, it appears that vomiting is a fairly efficient means of ridding the body of caloric intake, particularly for large binges. (p. 971)

OVERGENERALIZATION

“Purging only gets rid of 50% of calories, you know – it’s not worth it.”

First, the 50% statistic is frequently offered up during psychoeducation and nutritional therapy with the hope that this knowledge will disincentivize individuals to binge and purge. While many quote this number in an attempt to reduce the appeal of and belief in utility of purging, there is little, if any, evidence beyond anecdotes for this “fact” to produce behavioral change, for one.[1]

Second, the 50% is too often applied transdiagnostically, taken to hold true for all individuals who experience binge and purge. However, both Kaye et al. (1993) and a similar study in Brazilian patients by Alvarenga, Negrão, and Philippi (2003), which found a similar number of calories retained after purging (around 1, 300), purposefully included only BN participants, meaning that neither of the (only) two studies on the topic examined this process in the binge/purge subtype of anorexia nervosa (AN-BP).

In the study by Kaye et al. (1993), participation was limited to individuals meeting DSM-III-R criteria for BN who were >85% of “average body weight” (ABW; now “ideal body weight” or IBW) in order to avoid the potential confound of low body weight. There were only 17 participants and they had a mean weight of 106% ABW (SD=12%), with individual ABW ranging 85% to 126%. This would seem to indicate that their results might be specific to cases where binge-purge behavior leads to weight gain or maintenance of normal body weight or overweight. Thus, these findings may not be generalizable to individuals for whom binging and purging results in weight loss or maintenance of low weight.

While individuals with AN-BP in general tend to have a marginally higher BMI than those with solely restrictive anorexia (AN-R), and while it is true that hypermetabolism is present far more often in AN than BN (de Zwaan, Aslam, & Mitchell, 2002), the notion that purging is ineffective as a compensatory behavior is incongruous with the fact that individuals with AN-BP can be markedly underweight (in some cases to a severe degree) while engaging in objective binges followed by purges.

Individuals with AN-BP frequently binge multiple times per day, every day, and while this presentation of symptoms along with severe weight loss is certainly extreme, it is not exceptional, and the crossover rate from AN-R of 58-62% (Eddy, Keel, Dorer, Delinsky, Franko, & Herzog, 2002; also see this post), makes the AN-BP subtype itself far from uncommon among those with EDs.

Even assuming considerable individual variation in purging motivation, thoroughness and effectiveness, hypermetabolism in AN versus hypometabolism in BN is not sufficient to explain why the 50% average is applicable to two groups with divergent physiological outcomes.

Repeated objective binges in highly symptomatic individuals can amount from 10,000 to even 30,000 calories or more during a single day. If 5,000 to 15,000 calories are being digested on a daily basis, it is implausible that this does not result in weight gain or higher body weight. Delayed gastric transit is also commonly seen in AN, and could therefore reduce the number of calories the body is able to absorb from a binge, as well as increase the length of time before digestion of a binge occurs.

NEGATIVE EFFECTS OF SPREADING MISINFORMATION

Even research-savvy clinicians may quote the 50% statistic to all of their patients, regardless of diagnosis and symptom presentation, figuring that at the very least, it can’t hurt. However, this may not be an accurate assumption.

Firstly, when the information told by clinicians conflicts with lived experience, it may be interpreted by the patient as indicative of the clinician not being knowledgeable about EDs, not believing the patient’s account of their own symptoms, trying to deceive them, or thinking that the patient is stupid. All of these have potential to contribute to difficulty in creating therapeutic alliance, which is one major factor found to be predictive of a positive outcome from therapy. Further, it can provide a rationale for reluctant or ambivalent individuals to disengage, quit, or avoid seeking treatment.

Secondly, employing the 50% statistic to instill motivation to curtail purging may be a beneficial part of psychoeducation, but clinicians should consider the context of the patient’s description of their symptoms (type, severity and frequency) or at least maintain flexibility in their belief in this “fact” when confronted with evidence that makes this an unlikely phenomenon.

Finally, using this tactic obscures the fact that EDs are problematic and conflict with myriad other personal values irrespective of what happens with weight.

CONCLUSION

How a small, in-lab study of 17 BN subjects came to be so widely misinterpreted is unclear. It would be great if self-induced vomiting was ineffective at getting rid of calories and that this knowledge alone was sufficient to prevent or stop this habit, but, for many people, this is not the case. Self-induced vomiting is terribly damaging to the body and carries significant health risks (Tetyana blogged about it here), but spreading misinformation or overgeneralizing findings–particularly when those findings directly contradict patients’ lived experiences–benefits no one.

Indeed, when clinicians discount or disbelieve their patients’ lived experiences, they might not only by damaging therapeutic alliance, but, more worryingly, inadequately assessing the severity of their patients’ illnesses and minimizing potential medical risks.

And before we are accused of promoting self-induced vomiting, an egregious claim in its own right, please remember: We are not saying anything Walter Kaye and colleagues did not already say back in 1993.

Note: This post was written jointly by Saren and Tetyana.

[1] This may be particularly true for those for whom purging is an chronic behavior which has become entrenched via malnutrition, low body weight, and/or repetition or when purging (with or without a preceding binge) serves an anxiolytic function, negatively reinforcing this as an emotion regulation strategy in response to stressors, rather than or despite of the primary weight loss objective.

References

Kaye W. H., Weltzin T. E., Hsu L. K., McConaha C. W., & Bolton B. (1993). Amount of calories retained after binge eating and vomiting. The American journal of psychiatry, 150 (6), 969-71 PMID: 8494080

Great post! As someone with AN-BP, I always found this piece of “psychoeducation” incredibly frustrating since it was so inconsistent with my experience. More problematic/dangerous, though, is the fact that I initially believed that purging was not effective. Rather than discouraging B/P, that actually encouraged me to use even more extreme and unhealthy measures to purge.

Thanks Kathleen,

Your point on engaging in more unhealthy or extreme behaviours is a really good one that I hadn’t thought of before.

I think it is harmful when clinicians lie to patients knowingly, and I think it is harmful when they don’t believe their patients because of false “understanding.”

If we are trying to prevent binge eating and purging by fear mongering about weight gain, then we are doing something wrong, I think.

Thank you so much for this post. I have had to deal with the 50% of calories are absorbed statistic(or variations) countless times over the years. To say it has greatly affected my trust in professionals is an understatement. And the mistrust caused by this research goes both ways. I have often had clinicians disbelieve me when I describe my daily binges, and been told it’s impossible I’m consuming tens of thousands of calories given my low weight.

” have often had clinicians disbelieve me when I describe my daily binges, and been told it’s impossible I’m consuming tens of thousands of calories given my low weight.”

That’s happened to me as well (and from what I’ve heard anecdotally from others, is not at all an uncommon experience). I have had to keep food logs for clinicians because they thought I must be overestimating by a factor of 10 due to AN-distorted beliefs about food and calories. Nope.

I think too that the danger with providing sufferers with this kind of information – particularly in the binge/purge sub type of anorexia – is that in the thick of their illness when their ‘disordered’ goals are to achieve weight loss, such information may (and from my experience as a carer, is more than likely to) lead to more vigorous purging, or to attempting other or adding other kinds of purging activities to compensate for the supposed lack of binge/purging as a ‘successful’ strategy.

I have been consuming between 6000 and 30000 calories per binge , daily for the best part of 20 years, I currently have a BMI of 15 and it’s never been higher than 19. Throughout my ED I have found this much reported lack of efficacy in purging enough evidence to completely discredit any kind of other input from any professionals of any level. It’s just simply not factual and makes sufferers who know very differently completely distrust

It it a small-scale study, but I keep wondering about that cluster of dots representing those cases in which calories consumed roughly equal calories retained. How is that possible? I mean, some foods can be hard to purge, but with an established routine..? Did the study say anything about the composition of the food consumed? E.g. stuff mainly consisting of sugars might get absorbed faster than someone can get rid of it, but on the whole, it leaves me a little puzzled especially in the context of proving efficacy. By the way, wouldn’t these findings indicate that people with smaller binges, probably those at the onset of BN or with high p/p frequency, would retain a lot of calories (relatively speaking), thus experience weight gain which might prompt them to seek out alternative/additional behaviours? Any insights on that? Personally, when I used to b/p in addition to more or less normal eating, I gained weight despite exercising lots, but when restricting + b/p, my heart almost gave out twice because of the rapid weight loss… despite the binges being the same amount, which would mean a sustainable amount of calories consumed. What I am trying to say is that calculating retained calories is quite futile and just gives suffers more incentive to distrust their bodily mechanisms…

Hi Kaliya,

The authors did not mention ED history, as far as I recall, so I wouldn’t assume “established routine.” Moreover, they had to purge into a bucket in a laboratory setting, not the same as purging in the privacy of your home. Regarding composition, they basically picked food from a vending machine (so, to be explicit, generally hard-to-purge content.)

The authors did not set out to prove efficacy. They wanted to find out the efficacy. They weren’t trying to prove that it was or wasn’t effective.

The authors concluded that purging is more effective for larger binges, but whether or not that leads to weight gain depends on too many other factors. Like, as you implied, whether the person is or isn’t restricting outside of the binges. So, I wouldn’t assume that those with smaller binges gain weight more readily. Proportionately, they may be purging less, but their overall calories retained count may be lower. For instance someone with a 4000 binge may be more likely retain only 25% whereas someone who had a 2000 binge may retrain 50%, but in both cases that’s 1000 cals retained.

I am not following how this gives sufferers more incentive to distrust their bodies.

Hi Tetyana,

Thanks for your reply. By distrust I meant something along the lines of https://scienceofeds.org/2014/11/11/recovering-from-an-eating-disorder-in-a-society-that-loves-fat-shaming-and-dieting/

There are so many assumptions about bodily mechanisms, but their validity varies for individuals.

“What if”, despite purging being effective (or not) on the whole, it turns out to be different for an individual? “Normally”, a fitness model diet will result in weight loss, a pound of fat equals X calories consumed/ worked off, a purge equals X % of calories retained, the body has a set weight to return to etc… what if it doesn’t work that way for someone? That’s the point where the distrust comes in: “Why is my body so different, why does it insist on being fat, so I am ugly after all, even my metabolism is wrong…” Given many sufferers propensity for numbers and calculations, I am not sure if it helpful to think about yet another figure (calories retained). I wasn’t critisising the study, just wondering about some possible implications