Scientists love classifying and categorizing things they study. But it can be a double-edged sword. Classification can lead to new insights about etiology or new treatment methods. But classification can also hamper our understanding. For example, researchers like to classify and study anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa as if they are two wholly separate disorders, but clinicians know that most patients fluctuate between diagnoses, and as a result often fall into the eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) category.

Nonetheless, if we keep in mind that the way in which we classify things can be very artificial and may not necessarily reflect some fundamental truths about the subject matter, we can focus on extracting the insights gained from the classifications.

In the case of eating disorders, classifying patients into subtypes may be useful for developing successful treatment approaches suited for particular patient subgroups.

Previous research on this topic has identified three personality subtypes that seem to “cut across eating disorder diagnoses” (Westen & Harnden-Fischer, 2001):

Three Personality Subtypes in Eating Disorder Patients:

- “dysregulated/undercontrolled pattern: characterized by emotional dysregulation and impulsivity”

- “constricted/overcontrolled pattern: characterized by emotional inhibition, cognitively sparse representations of self and others, and interpersonal avoidance”

- “high-functioning/perfectionist pattern: characterized by psychological strengths alloyed with perfectionism and negative affectivity”

Heather Thompson-Brenner and Drew Westen wanted to build upon the initial findings and find out if this classification was valid. What makes a classification valid? In this case, a classification would be valid if it held some predictive value about the patients’ treatment responses, for example.

If the subtypes are valid and clinically relevant, they should differ in adaptive functioning, aetiological variables, patterns of comorbidity, treatment response and therapeutic interventions selected by the treating clinician.

In this study, Thomspon-Brenner and Westen focused on patients who exhibited bingeing and/or purging behaviours, so the data I’m going to talk about is coming mostly from bulimia nervosa patients. They asked a random sample of clinicians, and specifically members of the American Psychiatric Association and American Psychological Association with 5+ more years of post-residency experience, to fill out a questionnaire about their most recently terminated course of psychotherapy with a female patient who had “clinically significant symptoms of bulimia'” and they instructed them “not to choose a case based on outcome, to sample both successful and unsuccessful cases.”

In one of the sections of the questionnaire, the clinicians had to read three paragraphs describing the “prototypical” patient that fit the specific personality profile. Then, the clinicians had to rate the patient on how well they fit each of the three personality subtypes (from 1-5).

SAMPLE DEMOGRAPHICS

Clinicians

- mean duration of clinical experience: 16 years

- theoretical orientation: 37% “CBT” or “primarily CBT”; 34% as “psychodynamic” or “primarily psychodynamic” and 29% as “other”

Patients

- mean age 28.5

- 17% rated as “poor”; 46% as “middle class”; 31% as “upper middle class” and 6% as “upper class”

- 72% met criteria for bulimia nervosa; 14% for bulimia nervosa non-purging type; 6% for anorexia-nervosa binge/purge type; and 8% for EDNOS

- 38% of the patients were previously diagnosed with anorexia nervosa

- 42% had at least one admission to a psychiatric hospital

- average number of binges/week: 4.6; purges: 4.2

- half of the patients engaged in excessive exercise

- a third took laxatives

- over half of the patients fasted

The clinicians were forced to make a categorical choice about which personality subtype fits their patient. In this sample, 42% of the patients were categorized as “high-functioning / perfectionistic,” 31% as “constricted,” and 27% as “dysregulated.” What’s more, 84% of the patients strongly resembled one of the personality subtypes (considered as a rating of 4 or 5 on a 5-point scale).

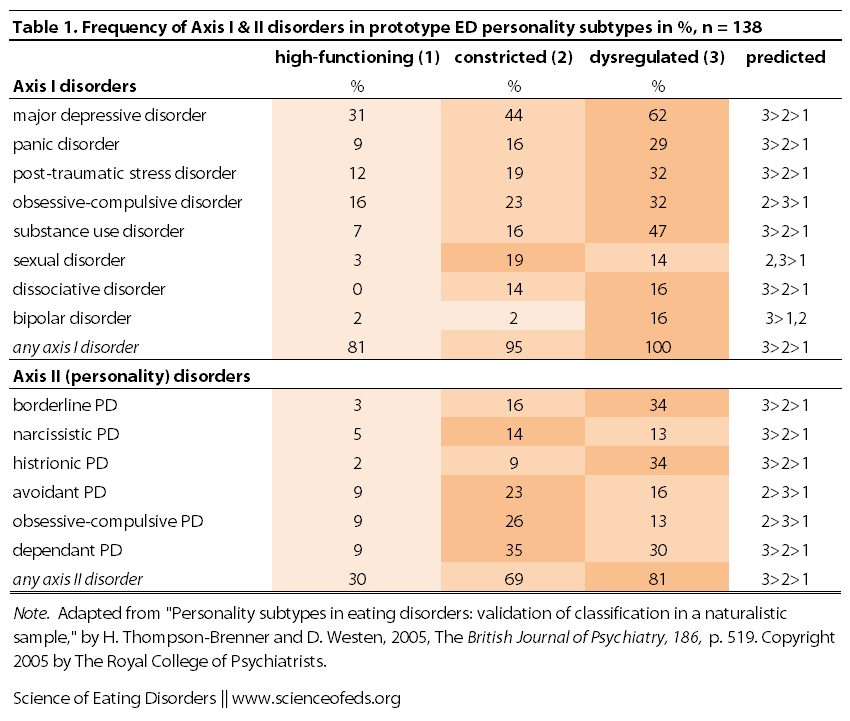

After the patients were categorized into the groups based on which of the personality prototypes suited them best, the authors wanted to find out if the subgroups of differed in terms of hospitalizations, history of child sexual abuse, and Axis I and Axis II disorders?

It seems that they did.

The dysregulated group had the highest rates of hospitalizations (62%), followed by constricted (40%) and high-functioning (29%). The dysregulated group also had higher rates of “clinician-reported childhood sexual abuse” at 42% (versus 20% and 19% for the constricted and high-functioning groups, respectively).

What about comorbidity with Axis I and Axis II disorders?

Clearly, there are differences. And with a few exceptions, the data mostly fit the predictions that Thompson-Brenner and Westen made before collecting the data. So, that’s great. But, why do we care? What’s the point of categorizing patients into these personality subtypes? Can this grouping tell us something useful about the patients?

After all, remember that

A valid psychiatric classification should ideally predict treatment response (Robins & Guze, 1970).

The short answer is, yes, it does seem that grouping patients based on these personality subtypes can tell us something about treatment response.

Thomspon-Brenner and Westen found that patients in the “dysregulated” and “constricted” groups spent longer time in treatment and had more negative responses to treatment.

Moreover, patients in the “dysregulated” group attained recovery after 92 weeks of treatment, compared to 73 weeks for patients in the “constricted” group and 51 weeks for patients in the “high-functioning” group. And, only 43% of patients in the “dysregulated” group recovered, compared to 50% in the “constricted” group and 62% in the “high-functioning” group.

I won’t bore you with the details, but essentially, Thomspon-Brenner and Westen found that these personality categorizations had a lot of predictive value in terms of treatment length and outcome that wasn’t there if we were to just look at eating symptoms or personality disorders for example.

Although the three types of patients were similar in their eating disorder symptoms (90% sharing the bulimia nervosa diagnosis), they also showed distinct patterns of comorbidity.

Patients rated as “dysregulated” had the highest rate of comorbid Axis I diagnoses and cluster B personality disorders. Patients rated as “constricted” were intermediate between the “dysregulated” and the “high-functioning” groups on Axis I comorbidity and were particularly likely to have cluster C (avoidant, dependent and obsessive–compulsive) personality disorders.

Personality patterns also predicted differences in treatment length and outcome. Dysregulation and constriction were both negatively associated with outcome. Patients in the constricted category attained recovery on average 5 months later than the high-functioning patients, and dysregulated patients attained recovery approximately 5 months later still.

Of course, there are limitations that should be noted: the data are retrospective and collected from clinicians (and it is hard to know if a rating “4” is the same for every person). It will be important to repeat these findings in a prospective study (as opposed to retrospective) and use multiple clinicians (or “informants”) per patients, if possible.

But anyway, why are these findings important? There are two main reasons.

1. These findings might explain the inconsistencies that we often see in research studies, since any given sample of bulimia nervosa patients (for example) is going to have a mix of different personality subtypes. This might explain contradictory results with regard to serotonin activity, for example, or associations with various personality disorders (say, if one sample has a higher percentage of “high-functioning” patients and another has a higher percentage of “dysregulated” patients, which may occur depending on how the sample was collected).

2. Perhaps more importantly, understanding the different personality subtypes may help clinicians treat patients better. How? By understanding the unique “patterns of thinking, feeling, and regulating impulses and emotions,” as well as knowing that a particular patient may require longer time in treatment or may have lower rates of recovery under conventional treatment modalities, the clinician might be able to change their treatment approach to focus on targeting “both personality and eating disorder symptoms.” This is in contrast to using the same CBT approach with different patients who may have very different personality characteristics (and thus, different “reasons” or perhaps “drivers” for engaging in symptoms.)

In any case, this is very interesting stuff, and I’m interested to see where it goes. And by the way, I think I would definitely fit into the “high-functioning group”: I’m quite an anxious person and I am somewhat perfectionistic (though I’m working on it, as you can probably tell: I don’t over-edit these posts, and while that means there might be a lot of annoying mistakes, it also means I’m not spending hours just editing spelling and grammar, which is a good thing in my books.)

What about you? And do you think having your therapist focus integrating both your personality characteristics and eating disorder symptoms in their treatment methodology would be (or would’ve been) helpful in your recovery?

References

Thompson-Brenner, H., & Westen, D. (2005). Personality subtypes in eating disorders: validation of a classification in a naturalistic sample. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 516-524 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.186.6.516

hm. This post irks me, for some reason. I think it feels too black and white, but of course I don’t think you were trying to come across that way. I definitely think I’m a mix of all three, perhaps leaning towards the dysregulated type a bit more (diagnosed AN-b/p so it does make sense). and it fits with my several, long, mostly unsuccessful hospitalizations. This last time I was IP, my team was more cooperative with me, letting me in on the decisions of my treatment, and deciding that long hospital stays didn’t work in the past and won’t work now. My IP team understands that it doesn’t help me, personally, to reach my target weight while IP, because that makes me sicker mentally and just wanting to get out to relapse again. So this time I decided when I would discharge, and so far I’ve remained pretty stable since I left last month. I’m doing OP, of course, and hopefully I can reach my target weight during OP, with a job, going to school, etc. all those real life stressors and triggers. I’m so fortunate that my team understands that and understands me. We’ve been working together for a long time and have known each other for years – I don’t know how many people have that relationship with their IP team. I’m very grateful.

Hi Heather,

Thanks so much for your comment. What about the post that irks you? What do you mean too black and white? As in, that you have to fit into the three personality types? It might be, and if so, that’s definitely my fault. I tried to emphasize that these are just constructs (or prototypes) that may be useful when thinking about treatment. Certainly, it is unreasonable to think that all patients with EDs fit neatly into three different personality types. I tried to emphasize in the beginning that these classification systems do not necessarily reflect some “deeper truth” about eating disorders, but they might help us understand how to tailor treatment to individual patients (and personality matters) and why research findings are sometimes contradictory.

I also struggle sometimes with reporting on findings where I don’t really like the naming or wording of things. In this case, I don’t like how “high-functioning” has a better connotation that “dysregulated,” to me, anyway. But, I wanted to stick with the wording in the study to be consistent in case I report on follow-up studies, or something of that sort. In any case, I think this research follows along the lines of the work that has shown that patients with more comorbid disorders don’t fare as well as those that don’t. I think that’s due to a lot of reasons: difficult to find treatment teams that understand all facets of your personality, comorbid disorders or dual diagnoses, the mere fact that recovering from several things is harder than recovering from one, and other issues that are unique to the comorbidity/other diagnoses (like diabulimia).

I also don’t think some of these things are static. I would love to a see study where patients are followed for like 5-10 years and how their personalities, or facets of their personalities, change over time. For me, having gone from anorexia-restricting type to AN-B/P and BN, and back and forth a trillion times (okay, not a trillion, but too many to count), I can definitely tell that during the AN-R times, I was much more on the high-functioning and/or constricted side of things, whereas during bulimia, I was more on the dysregulated side, though anxiety is something that I realize has been an ongoing thing through-out and I’ve never struggled with depression, self-harm, panic disorder, PTSD, substance-abuse, dissociation, etc.. I think if anything, I have mild generalized anxiety. But I think the nature of bingeing and purging almost always (though I wouldn’t say always) implies increased impulsivity to some extent.

I’m really happy that your team listens and trusts you. SO IMPORTANT. Crucial, really, because if they don’t trust you and you don’t trust them, what real treatment can really happen, right? My personal take is that while it may be a lot harder to recover in the “real world” (with school, work, etc..) I feel (and this is my personal opinion, not some scientific fact) that it is more “meaningful” because so many people relapse as soon as they get out of intense treatment and face the real life stressors and triggers. I think recovering slowly with the stressors and triggers side-by-side means that you’ll be less likely to relapse when faced with those stressors and triggers. But that’s my personal opinion. (And of course, the option to do this should be applicable to those who are medically stable and want to do this.)

Thanks for commenting. And do let me know if there’s any way I can improve how I write the posts and get the info across.

Cheers,

Tetyana

Tetyana, I think your post was fine! Although, the same as you, I don’t think I quite liked the wordings of these findings, but I commend you on doing your best to write a blog post about them. I think you and I both know that there is so much grey area especially in the treatment and study of eating disorders, in eating disordered people themselves, their behaviours, etc. It ISN’T static. It ISN’T black or white.

I’ve also gone from AN-R to AN-BP and I’ve found the same – things are different even within the sub-types, we flow and shift with the shifting of our behaviours, malnourishment, what our brains are reacting to, etc.

Anyway, I think you did the best you could with this post. I love your site. 🙂 You do a fantastic job.

Thanks Heather!

I’ve written this before, but there was a period during my eating disorder where I used to binge and purge in spurts (like once I started, it would be 3-4 days of near constant bingeing and purging) but once I’d stop, I’d be okay for a week or so, mostly restricting, though. And the change in my mood, schedule, focus, emotional state, productivity, would be like night and day. Like I said before, my partner would know that I’m feeling better (ie, out of the bingeing/purging state, or just purging all meals) because the house would be clean, I’d be up early, go to the gym, do some work in the morning, etc.. Total switch. And we are talking about very small time frames, too. Of course, in the grand scheme of things, there are things that are more or less stable, but I do wonder whether things are really stable or we just think they are (as a post-hoc rationalization of our behaviour). I always think about this… always.

Tetyana

I relate. It’s so strange, that shift, and how we perceive things (which may or may not be how things are in reality).

take care. xx

It’s interesting because, despite identifying most with the “high-functioning” personality type (anorexia b/p at the moment), I instinctively reject it. I want to be the “dysregulated” personality, perhaps to explain or excuse my eating disorder, but mostly to gratify my need to be sick. Perhaps it’s part of the competitiveness of eating disorders but I immediately felt like these individuals are “worse off” and I struggle greatly with that. I don’t want people to get the impression that my eating disorder and other mental illnesses or my recovery are easier than for others..it’s almost invalidating.

I’m not trying to say that your article is giving that impression but that’s the way I initially took the personality type findings. (Time to challenge disordered thoughts, I suppose.)

Great article! I definitely think it would be helpful if a therapist integrates both personality characteristics and symptoms in treatment methodology. I think they would need to be careful to not lean on one subtype too much though.

BTW: I didn’t catch any grammar mistakes 😉

Kinda late to the party here 😉

I think I fit into all three, and quite neatly that is. Which does make me feel really chaotic, as I’m sure it does make my therapist. My problem in treatment has been how I don’t fit the boxes and get he feeling people don’t know how to approach me. I’m a high functioning chaos. Diagnosed with BPD, although I self identify as a quiet-BPD, my chaotic side can get really out of hand, and I’m suspicious of people and motives and constantly fear their rejection. I can be quite impulsive – hello shopping! At the same time, I’m really perfectionistic towards myself mostly but I can also be hard on people if I sense they are not up to the professional standard I expect. And the high functioning part. Numerous years of ED – nobody had a clue before I told them. and I’ve accomplished quite a lot. With the aid of perfectionism as well as the impassivity of going for it. And that’s also been the manifestation of my ED. Controlled binges in secrecy – always completely alone and in between – long periods of heavy restricting, that was also very controlled and “healthy” since I was very concerned with vitamins and all that stuff as well. So yeah. Don’t really know what to say, as I feel I fit nicely into all and thus nowhere at all since I don’t present like “textbook ED” of any of the diagnoses.

I don’t know whether I would fit constricted or high-functioning – probably somewhere between the two.

I started with AN restrictive – pretty text book case from what I’ve read – but began to binge during recovery and ended up with some kind of EDNOS where I would restrict for months then binge for months.

I would say it has been useful for me to have therapy (recently) that focuses specifically on emotional inhibition and on my associated difficulty knowing how I feel about things, creating social bonds, and feeling things like warmth and pleasure rather than a kind of constant flatline of nothingness. It would not have occurred to me, had it not been pointed out, that I don’t know how I feel or that I often fail to respond at all to what most people would consider to be emotionally stimulating events. If you don’t feel it, it doesn’t seem like a problem.

I can’t speak for those who are on the other side of the scale, of course, but for me specific attention to the fact I overcontrol emotions and help for me to understand how that mechanism works (I have a kind of in-built, unconscious CBT machine that changes my thoughts to de-emote situations, thereby keeping my emotions from rising – but this is an extremely stressful thing to do so I always feel tense, unfulfilled and trapped), has helped me understand how I can help myself. In essence: Notice that tension, relax, let whatever is happening happen – feel whatever feeling I might be about to feel. Notice the desire to control something in my life (weight, work, etc.) and sit with it rather than acting on it. Allow things to ‘get out of hand’ for a second or two. It certainly helps me to feel more alive.

The other thing is that because I have a dim view of emotions (trying to change this but I tend to think vulnerability is for weak people and children), some therapists have unintentionally driven me away by talking about emotions openly and accusing me of having them, which I found so incredibly offensive that I was on the defensive with them from the start. I know it’s just my judgements and that’s completely irrational, but therapists using an approach where they consider what irrational judgements you might have about emotions might help me trust them rather than just jumping in assuming I “fear abandonment” or whatever they’re going to say, because in the past when therapists jumped straight to talking as if I had vulnerabilities I felt they were speaking down to me/treating me like a child/had no respect for me etc., so it encouraged me to control more and to show no emotional expression to “prove them wrong”.