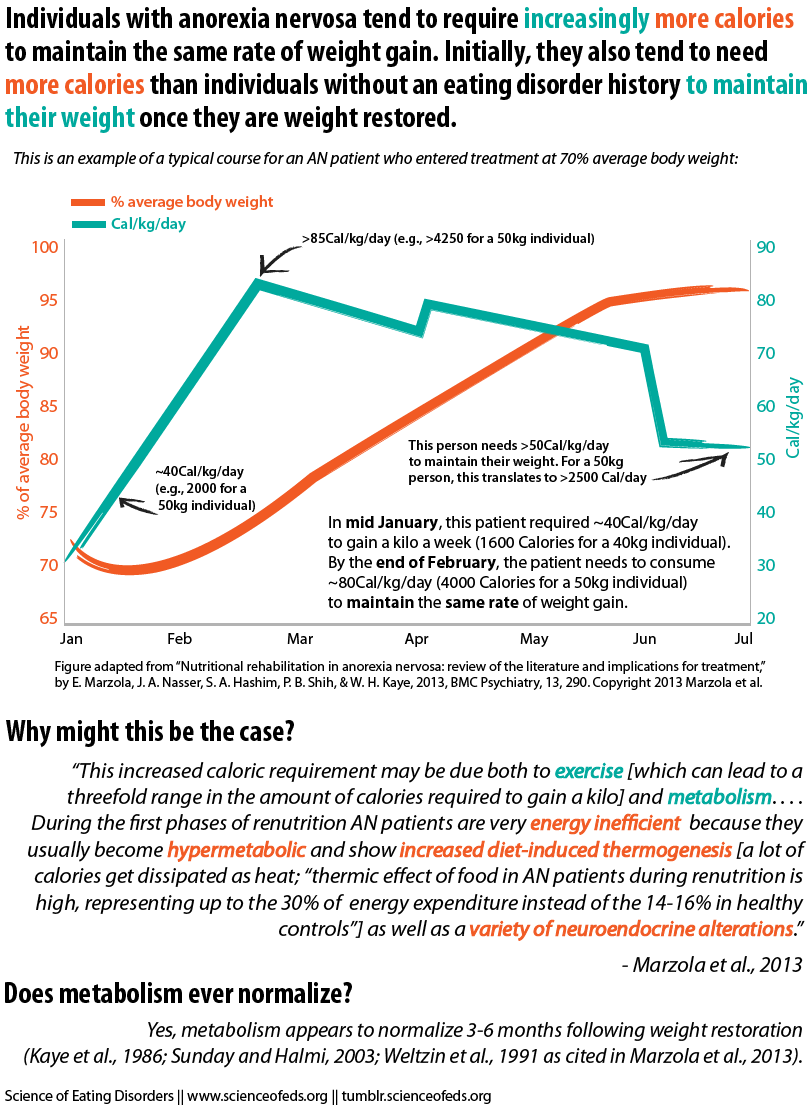

Weight restoration is a crucial component of anorexia nervosa treatment. It is a challenging process for a multitude of reasons. Adding to the complexity and the challenge is the fact that during weight restoration, individuals with anorexia nervosa tend to require increasingly more calories to maintain the same rate of weight gain.

That is, individuals need to continually increase their caloric intake, in steps, sometimes upwards of 100 calories (technically, kilocalories) per kilogram per day, to continue gaining weight. For instance, an individual weighing 45 kg may need to eat 4,500+ calories to continue gaining 1-1.5kg (2.2-3.3lbs) a week. Indeed, studies have found that standard resting energy expenditure (REE) equations tend to overestimate caloric needs at the beginning of refeeding but underestimate them in the later stages (Forman-Hoffmann et al. 2006; Krahn et al., 1993).

After achieving a healthy weight, individuals recovering from anorexia nervosa still typically need to eat more calories to maintain their new healthy weight — more than healthy individuals of the same weight who do not have eating disorder histories — usually at least 50 to 60 calories per kilogram per day (e.g., about 2500-3000 calories for an individual weighing 50 kg (110 lb). This hypermetabolic periods tends to last between 3 – 6 months after weight restoration.

The graphic below shows the typical course of weight gain and calorie intakes for someone entering treatment at ~ 70% of average body weight for that height:

I do want to be clear that studies on metabolic rates, calorie requirements, and weight gain vary widely in their results. According to Salisbury et al. (1995), some studies have shown that individuals with AN need to consume an average of 5,350 extra calories to gain a kilo whereas others have suggested that the number is closer to 9,750 — that’s a big range. This may be due, in part, to methodological differences between studies, lack of differentiation between AN subtypes, and small sample sizes. And, as I blogged about in my last post: exercise. Exercise can lead to a threefold range in the amount of calories that individuals with AN need to gain (and maintain) weight (Kaye et al., 1988). As Zipfel and colleagues (2013) show, this is, at least in part, due to the higher calories needs of lean body mass among AN patients who engage in (excessive) exercise.

Still, what might explain the increased caloric requirements during refeeding? The most obvious answer is of course weight gain itself: As individuals gain weight, they require more calories to maintain that weight. Moreover, gaining 1 kg of fat requires more calories than gaining 1 kg of fat-free mass (9300 vs. 5300 calories). If individuals are gaining more fat mass during the latter stages of the refeeding process, then they would require more calories to gain 1 kilo:

Overall, the body composition data seem to suggest that at least 50%, and perhaps more, of weight regained is fat tissue. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the average excess number of kilocalories required to gain 1 kg of body weight in these studies was 7,462, which is approximately the average of 9,300 and 5,300 kcal (required for the gain of 1 kg of fat and protein, respectively). Furthermore, it may be that the initial very low body weights and percent body fat predispose [AN] patients to gain more lean tissue than fat early in refeeding. As patients approach a more normal weight later in refeeding, more fat than lean tissue is gained.

In addition to weight gain, there’s also the fact that patients with AN appear to be metabolically inefficient. Evidence suggests that individuals with AN convert more energy to heat (as opposed to building tissue) than do healthy controls:

Our clinical experience is that AN patients often complain of becoming hot and sweaty during nutritional restoration, particularly during the night. It is not uncommon that they will wake up sweating and their sheets are soaked. . . . This notion is supported by studies showing that the thermic effect of food in AN patients during renutrition is high, [63,65,66] representing up to the 30% of energy expenditure instead of the 14-16% in healthy controls [67] and being particularly high at the beginning of refeeding [65].

Some previous studies found that AN patients who binge and purge require fewer calories than AN patients who don’t. According to Sunday and Halmi (2003), however, those findings may have been due to differences in lean body mass vs. fat mass on admission. Individuals who have proportionately more lean body mass will require more calories to gain and maintain weight compared to those who start out with proportionately more fat mass (Sunday and Halmi, 2003).

Conversely, previous studies (e.g., Stordy et al. 1997, Walker et al., 1979) have found that patients with a history of obesity tent to need fewer calories to gain and maintain weight compared to patients without a history of obesity.

Despite decades of research we still don’t know all that much about metabolic changes during and immediately after refeeding. There’s a lot more research to be done. But for now, I’ll leave you with some practical suggestions regarding nutritional rehabilitation and weight gain.

From Mehler et al. (2010):

Caloric requirements for weight restoration in patients with anorexia nervosa are best determined by monitoring an individual’s rate of weight gain. Given this dynamic process, caloric requirements may have to be recalculated if weight gain is not being achieved as expected during the refeeding process. . . .

Ultimately, as the process of refeeding progresses and [ideal body weight] is achieved, very high levels of caloric intake may be temporarily necessary (70 to 80 kcal/kg) to promote ongoing weight gain. It has recently been elucidated that refeeding a patient with anorexia nervosa may be associated with an actual increase in REE during the weight gain process. Although the mechanism of this phenomenon is presently unknown, its clinical implications are quite clear: unusually high-calorie diets may be necessary to provide continued weight gain towards the end of the weight restoration process. A plateau in the desired rate of achievement of a patient’s target weight may be observed because of underestimation of caloric needs during the late stages of weight restoration due to the aforementioned change in the REE value.

Finally, to conclude, I’ll quote Marzola et al. (2013):

To obtain the best chance of long-term weight maintenance recovery, AN patients should persist with an increased [and varied!] caloric intake treatment plan.

Please keep in mind that this post was meant to be a very short and relatively simple overview of a complex topic, so, as always, feel free to ask questions if something is confusing or if you feel I overlooked something important. I really appreciate it :-).

References

Marzola, E., Nasser, J.A., Hashim, S.A., Shih, P.A., & Kaye, W.H. (2013). Nutritional rehabilitation in anorexia nervosa: review of the literature and implications for treatment. BMC Psychiatry, 13 PMID: 24200367

Thanks for highlighting these important metabolic effects, Tetyana 🙂

The main question I have always asked is ‘How is one supposed to eat All Of That Damn Food?’.

On a personal level, I find the hypermetabolism of restrictive EDs incredibly depressing on account of (1) my emetophobia; (2) my OCD; (3) my autism.

Too much fear and anxiety all round 🙁

Cathy How does one eat all the food? Good question- its like a catch 22, as I found in order to get anywhere near the amount of calories that was required to refeed myself, I was going to have to eat my fear foods all the time. High fat, high calorie nutrient density. That in itself presented me with a massive obstacle to try and climb.

Thanks Tabitha… I don’t have specific ‘fear foods’ though. The higher the calorie value the better. My fears relate to feeling the food in my stomach (triggers emetophobia) and whether the food is contaminated (I have OCD).

Hey Cathy! Nice to see a comment from you!

Have you found that drinking calories is easier than eating them? That might be one (part of a) solution.

It has been quite a while since I was at the NYSPI unit, so I don’t know if this is still the case there, but … Once you reached a certain number of calories/day, all other increases came from supplements (EnsurePlus) given three times a day (snack times). There wasn’t a limit to the number of Ensures you might receive … someone with walking or pass privileges usually picked up a very large tumbler at a dollar store for those who were treading into the lots-n-lots-of-Ensure protocol … several cans at a time, in some cases, in addition to meals.

In other approaches: I haven’t been a patient there, but I know many people who have been treated at one or both of two well-known residential programs/chains that use NG tubes to achieve calorie density/increases. I disagree with standard use of feeding tubes, but others say it was easier to just have it running at night and not have to eat massive amounts of food multiple times a day.

The program near me, where I have most frequently been a patient, doesn’t subscribe to either of the above. You choose your own menus for whatever calorie level you’re on. If the patient wants to order supplements with their tray, you can do that.

The RD usually promotes “condensing,” or choosing combination foods, entrees and casseroles that have density, a lot of exchanges in a serving size. Actually, they won’t let you order five servings of cereal or multiples of “safe,” foods vs. something like French toast with butter and syrup, eggs, whole milk, peanut butter, etc., and if you try to avoid condensed foods, they will arrive on your tray, anyway.

Thanks and sorry for the delay in responding, Tetyana… Liquids are easier for me than high volume solid food. I find the only way that I can sustain an energy intake adequate even to maintain my current underweight state is to consume chocolate, cakes and energy dense foods. I am not what one might call a ‘healthy eater’ at all!

Thanks for yet another helpful article!

Do you know if any studies have looked at the metabolic differences in people with AN looking at length and severity of the disorder? I wonder if a person who remains at a low weight for a longer period of time will require fewer calories for weight gain/restoration because their metabolisms have essentially become more efficient and slowed down due to a longer period of time with insufficient intake.

And with longer periods of time being underweight, I also wonder how much exercise factors into the equation. I imagine a person who remains engaged in exercise (even if not excessive) would begin with a higher REE than a person who becomes more sedentary as the energy stores are less available.

I also wonder whether the degree to which the person has restricted their intake affects the gain/restoration amount needed. So if a person who has “achieved” their low weight has done so over a slower period of time consuming more calories vs. rapid weight loss with severely restricted intake changes the equation at all.

So many factors involved!!! It’s all so fascinating!

Thanks Sarah! With regard to your first and third questions — I’d have to look into it. I’m afraid I don’t know much about metabolism (it has never been something that interested me all that much to be honest), so I’m afraid to even hazard a guess. I bet some of the answers (or clues) to your questions may be in a different field (not necessarily eating disorder literature). Good questions though! Regarding your second question — yes, you are right. I blogged about that here actually. Patients who exercise more do have higher resting energy expenditures. In fact, according to the Zipfel et al. (2013) study, it seems that they have higher metabolic requirements per kg of lean body mass.

Thanks for your follow-up Tetanya!

It’s hard to find good information on underweight individuals that isn’t ED related. Most research these days is looking at reducing weight, rather than gaining. I’ll have to keep looking though.

And I don’t know why I asked my second question or what I was trying to get at with that… I remember your other post about it. I think I even commented! Ha ha. So thanks for the reminder!

What if I’m underweight for my height, but close to 50kg as noted but maintaining at this weight at lower than 800 calories/day? How could I possibly eat 2000+ calories and not balloon?

I believe my thyroid is messed up and my overall metabolism is too slow for it to be normalized, especially after 15-20 years of on/off anorexia.

Hi Susan, you are likely to be metabolically suppressed and so if you begin to increase your intake, your metabolism will likely speed up.

Susan, for what it’s worth I think of our bodies like a companies and the food we eat is similar to that of the income coming in to run the business. When less money is coming in, employees have to be let go and others have to take up the slack and therefore cannot do their job as efficiently or as effectively. Projects only get partially competed or not at all. The company can run okay for a short time while employees are on vacation, but they are still needed in the long run to make sure their jobs are being completed the most effectively. So when we restrict our caloric intake beyond what is necessary, it’s like we are operating as if some of our employees have been on extended vacations or let go due to insufficient funding, but because they do have very essential jobs nothing works as smoothly or as effectively. So while yo may be maintaining your weight, the likelyhood that all the metabolic reactions that are truly necessary for proper functioning are not happening. Your “company” is operating on bare bones minimum and not doing the best it can because everyone is so over worked yet they still don’t have time to get everything done. When you increase you caloric intake it will be like those employees coming back on payroll and it will allow for more of those reactions to occur (and make your body much much healthier) and it therefore requires more money to pay everyone – aka energy to complete all of the reactions. And also remember that adipose tissue is a huge regulator of hormonal activity, so when one loses too much of it hormones go wacky which can also disrupt the workforce, so once that gets normalized the whole company works much better! I’m not sure of that helps at all, but that is how I like to think about it…

This is really interesting in the context of inpatient treatment where patients can be suspected of exercising / interfering with weight gain when it begins to slow/reverse, especially if this happens later on when more freedom with meals / activity is usually given.

Do any of the studies look for a duration effect of AN, do you know? I was wondering if the length of time that the body body spends at a low weight affects how quickly weight would be restored, or if an individual’s set point is lowered after a long time at a low weight, that this person might require even more calories to raise it again.

Not sure I understand the bit about lean mass being gained before fat mass in someone who is very underweight, or does that only happen if energy requirements in refeeding aren’t quite optimal?

Hi Zoe,

I think your first question is similar to Sarah’s? Unless I’m not understanding it correctly. If so, I’d have to look into it. I really don’t know. I’d assume it would affect it somehow but I’m not sure how.

Regarding lean mass — it seems that (according to this study, maybe others but this is the one cited in the paper), individuals at very low BMIs preferentially gain fat mass in the initial stages of the refeeding process and hence require more calories to gain a kilo than individuals at higher weights (because it takes more calories to gain a lb of fat mass than lean mass). From the Marzola et al. paper:

An important aspect of metabolism to consider during refeeding is the 6-fold greater energy requirement needed for gaining fat mass versus fat-free mass [73]. It is possible that during nutritional restoration more fat-free mass is initially synthesized in those with Body Mass Index (BMI, expressed in kg/m2) between 13 and 14 compared to those patients with BMI > 14 [73].

I hope that clarifies it? Maybe my wording was confusing in the post (going to go check now).

Very interesting presentation of the facts! I’m curious to read the responses to the questions posed in comments above.

Sorry yes, for some reason, I couldn’t see any of the other posts when I first read the article, so I have more or less just repeated Sarah, it seems!

Regarding the preferential gain of fat versus lean mass, I was more thinking about whether the type of mass gained is influenced by the number of calories given in refeeding, but the study doesn’t seem to suggest that. (I’m now wondering that if the control of lean versus fat mass gain is an endocrine thing, might it be different in people at low weights who still menstruate?)

Hi guys,

I have hit rock bottom and am so upset and confused! I recovered from anoexia at the beginning of this year and was really muscular and had my period and was happy and healthy. I upped my exercise this year and have gained weight but it’s all fat (not just my perception as I had a full body scan which showed that I have indeed lost muscle tone and gained significant fat). Do you know why this is happening? Will I ever be muscular again or am I doomed to be soft for life? 🙁